- English

- 简体中文

- 繁体中文

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- Español

- Português

- لغة عربية

Kevin Warsh’s Fed nomination: implications for rate cuts, balance sheet policy and communications

Summary

- Rates & Balance Sheet: Kevin Warsh is likely to favour near-term rate cuts, though efforts to significantly shrink the balance sheet seem unlikely, even if asset holdings are likely to become somewhat tidier

- Other Changes: A reduction in the frequency of public speeches, potentially including a reduced number of press conferences, as well as a shift away from 'data-dependency' all seem likely too

- Confirmation Hurdles: Confirmation to the Board, and eventually to the Chair role, however, may not prove simple, with numerous senators planning to block nominations until the DoJ's probe into the Fed concludes

With President Trump having now announced the nomination of former Fed Governor Kevin Warsh to succeed Jerome Powell as Chair of the world’s most important central bank, now is an opportune juncture to sketch out what a ‘Warsh Fed’ might look like.

Importantly, and frustratingly, for the purposes of this exercise at least, Warsh has been relatively reclusive in recent years. That said, having been known as a ‘hard money hawk’ during his stint on the Fed Board from 2006 – 2011, Warsh appears to have undergone something of a damascene conversion to adopt a considerably more dovish approach in recent years, which to a large extent does appear borne out of political expediency, as opposed to any developments in the underlying US economy.

Still, tying together some of Warsh’s remarks over the last couple of decades still allows us to build a picture of how he may attempt to shape the Fed, assuming that his nomination is confirmed by the Senate.

Lower Rates

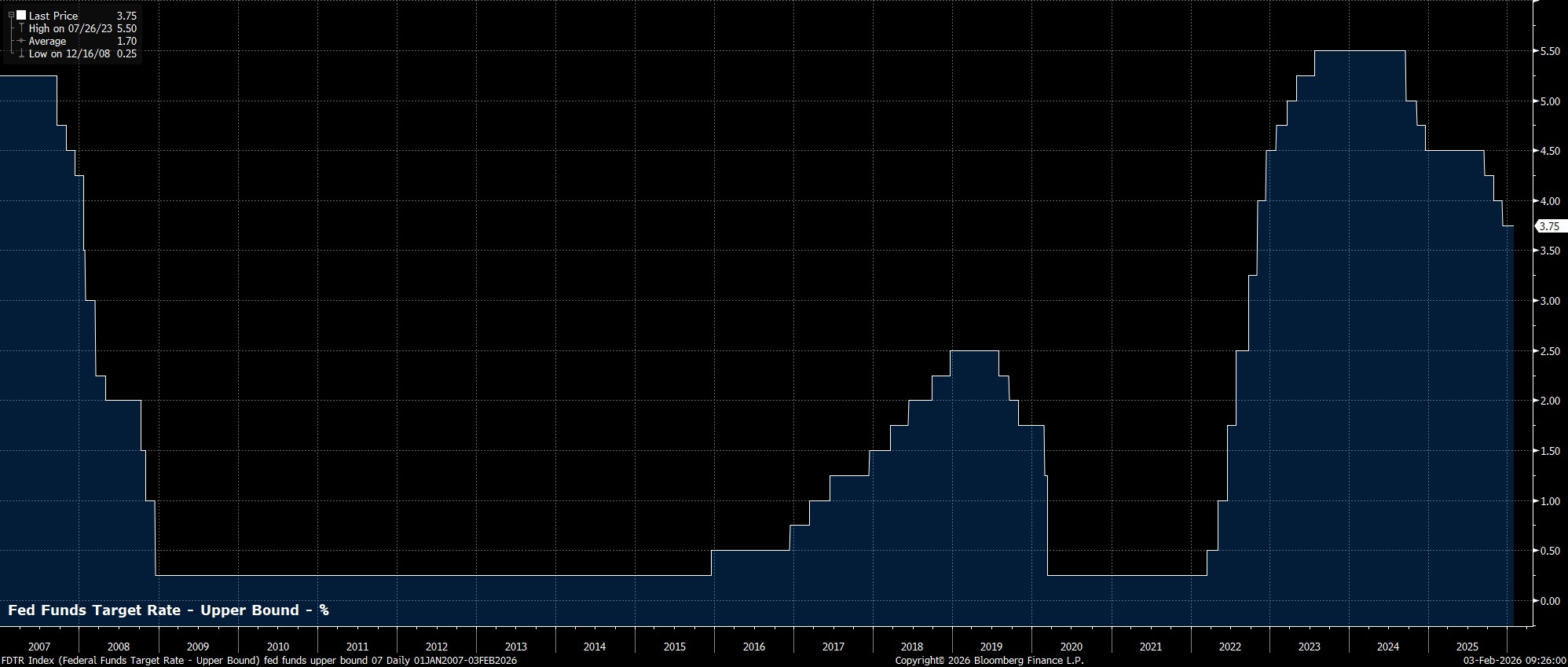

Perhaps a given, considering that President Trump is hardly likely to appoint a Chair who’s reluctant to lower the fed funds rate, though it still bears saying that Warsh is likely to push for rate cuts as soon as his first meeting at the helm, almost certainly in June.

Of course, Warsh will have to build a cogent case supporting the need for such rate cuts in order to obtain support from the remainder of the Committee, with his prior views on this front having centred around a belief that policymakers should ‘look through’ tariff-induced price pressures, while also buying into the idea of a disinflationary productivity boom fuelled largely by AI.

A Tidier Balance Sheet

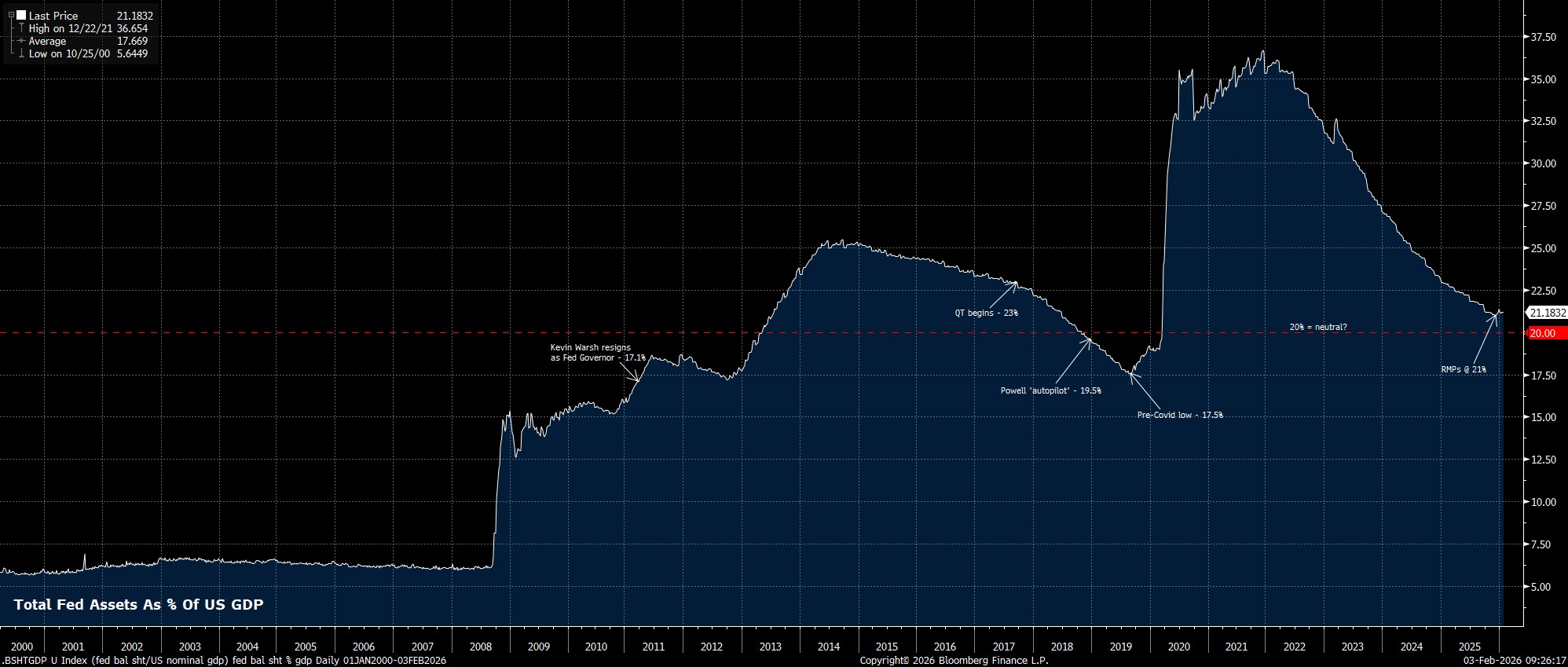

Warsh’s views on the balance sheet are well-publicised, given his belief that it is not only ‘bloated’ but also ‘trillions of dollars larger than it needs to be’. Those statements, though, are somewhat ridiculous in a broader context, with the balance sheet presently amounting to around 21% of GDP, compared to 17% of GDP on the day that Warsh resigned in 2011 – barely a difference, in the grand scheme of things.

Moreover, Warsh is unlikely to find much, if any, support on the FOMC for an outright shrinkage of the balance sheet, especially with his view going against conventional wisdom – as well as my own view – that a smaller balance sheet would exert upwards pressure on market-based interest rates, in turn running counter to the Admin’s aim to lower rates across the curve, and improve ‘affordability’. There is also the issue of the Fed’s ‘ample reserves’ operating framework, which as we are now seeing requires a gradual expansion of the balance sheet over time in order to maintain control of interest rates, and ensure that no financial plumbing issues emerge.

Changes to the Fed’s framework are possible, though shan’t be particularly rapid. Something akin to an ‘operation twist’, however, could be more palatable and possible in the short-term, particularly with officials such as Governor Waller having previously advocated for a shift in the portfolio towards shorter-duration securities.

One must also consider the issue of MBSs here, though once again any significant reduction in holdings contrasts significantly with the Trump Admin’s ‘affordability’ aims. Perhaps, there is a way in which those holdings could be shifted onto the balance sheet of the Treasury, via the GSEs (Fannie Mae & Freddie Mac), though that is probably a matter for consideration at a much later date.

Dialling Down The Fedspeak Volume

Warsh has been a noted critic of the Fed’s communications in recent years – which, to be fair to the Warsh, is hardly something he has been alone in criticising. In any case, Warsh has remarked on numerous occasions that policymakers should discuss their economic outlooks less frequently, owing to a belief that ratesetters ‘can become prisoners of their own words’ once their outlooks are made public, and that ‘waxing and waning with the latest data release, is…counter-productive’.

These remarks suggest that a ‘Warsh Fed’ is likely to prove a less transparent one, but also one where on occasions when policymakers do make remarks, they are likely to prove more significant and substantive in nature, in turn heightening volatility around the rarer opportunities that we do hear from FOMC members.

Taking account of the above, there is also the potential for the frequency of post-meeting press conferences to be reduced, perhaps via a return to the pre-Powell norms where a press conference was only held at a meeting that coincided with the release of the quarterly Summary of Economic Projections (SEP).

SEP Changes

On the subject of the SEP, changes here are also likely.

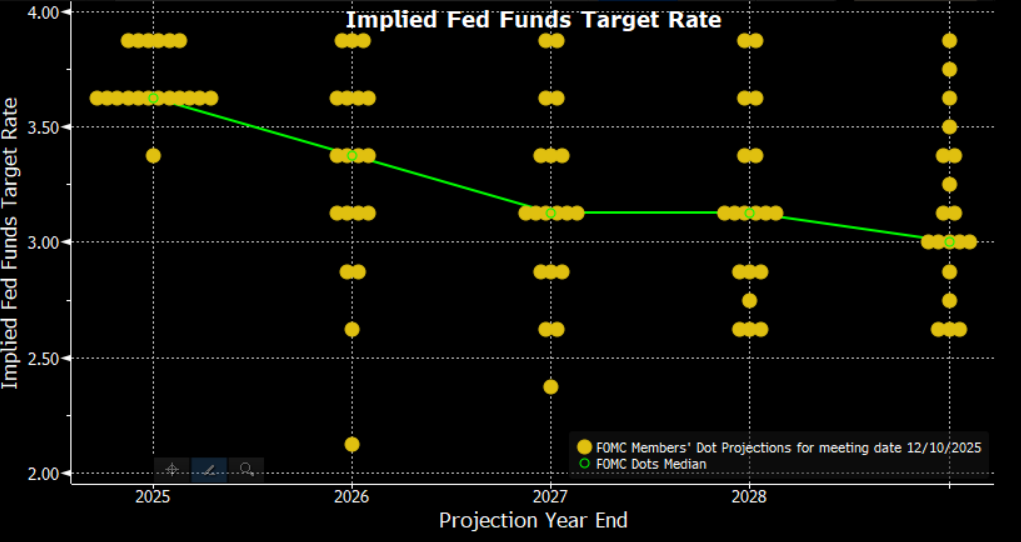

Firstly, the frequency of the SEP’s publication, currently quarterly, could be reduced, owing to Warsh’s distaste for frequently communicating an economic outlook, with there also being the potential for the SEP to be done away with in its entirety. Assuming that the SEP does stay in some form, the ‘dot plot’ does seem likely to be consigned to the history books, with Warsh having also noted that forward guidance ‘has little role to play in normal times’.

In a similar vein, Warsh’s desire to move away from an explicit dependence on incoming data, amid a view that such dependency results in ‘false precision’ and ‘analytic complacency’, also suggests a preference to water down the SEP. Still, if the Fed plan not to regularly present an economic outlook, while also being apparently unbothered about incoming data, this suggests an overall high degree of rigidity to the policy framework, while likely also stretching credibility to a significant degree, potentially troubling financial markets, particularly at times of stress.

Confirmation Hearing To Bring Clarity

Much of what we know about Warsh’s views, at this stage, is gleamed from a combination of policy stances from almost two decades ago during his prior stint at the Fed, as well as a small number of public remarks made in the intervening period. Hence, the upcoming confirmation hearing, held on a date TBC by the Senate Banking Committee, will be of particular interest, as it will provide the first opportunity for Warsh to outline his views on the economic outlook, the appropriate future path for monetary policy, and the Fed’s overall operating framework.

That said, confirmation could prove far from straightforward, with the DoJ’s probe of the Fed’s building renovations ongoing, and numerous Senators, including GOP Sens. Tillis and Murkowski, having pledged to block any nominees to the Fed Board until that matter is resolved.

Incidentally, it is likely that Warsh will require two Senate hearings, assuming that he is first nominated to fill the Governor seat recently vacated by Steven Miran, before later being nominated to the Chair position. In fact, with there being no guarantee that Powell leaves the Board before his term as Governor expires in 2028, this is the only certain way for Warsh to obtain a seat.

Policy Implications

All that said, the near-term policy implications of Warsh’s nomination are close to non-existent, with the Fed set to remain in ‘wait and see’ mode for the time being, having taken out 75bp of ‘insurance cuts’ against further labour market weakness at the tail end of last year. Still, if Warsh is confirmed prior to the March or April meetings, one can expect a dovish dissent, with the narrative around that dissent of particular interest.

Looking ahead, to when Warsh takes the helm, key will be whether he is able to persuade other members of the Committee of his likely more dovish approach. If he’s unable to do so, we may end up in the rather embarrassing situation of the Chair being outvoted by the Committee, before having to explain the entire thing at a post-meeting press conference. We shall leave that potential ‘can of worms’ for another time.

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.