- English (UK)

Background

After the previous ‘traffic light’ coalition, headed by Olaf Scholz’s SPD, along with the Greens, and FDP, collapsed in late-2024, as a result of Scholz ousting then-finance minister, and FDP leader Christian Lindner from his Cabinet, Germany will now head to the polls in its fourth post-war snap federal election.

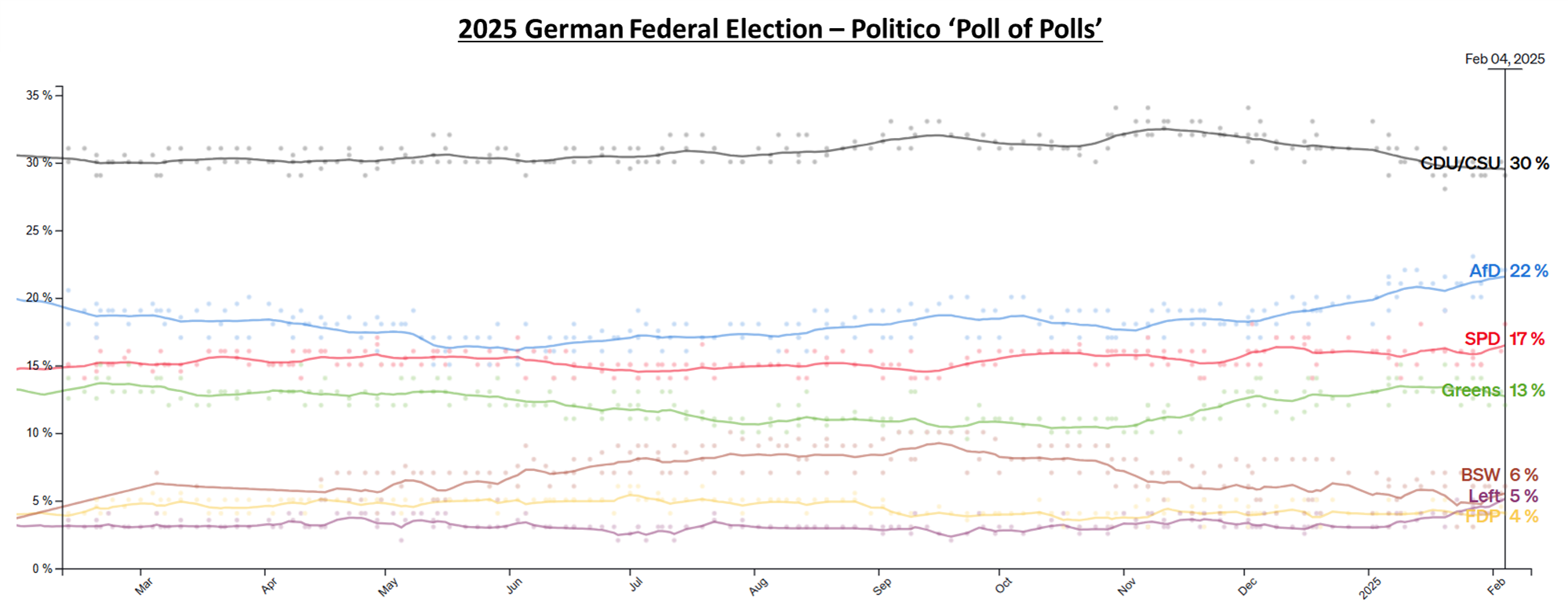

Polling for the election points to a clear lead for the CDU/CSU, headed by Friedrich Merz, and currently the main opposition party in the Bundestag, with most polls showing support for the ‘Union’ standing at around 30%. Meanwhile, the far-right AfD party stand second in most opinion polls averaging around 20%, with both the SPD and Greens languishing behind on approximately 15% apiece. Support for the FDP, and far-left BSW, is shown as below 5% in most polls.

Electoral System

Importantly, the percentage that a party achieves in pre-election opinion polling, and in the election itself, does not translate directly into the number of Bundestag seats that said party wins.

Firstly, Germany uses a mixed-member proportional electoral system, which hands each voter two votes. The first is a vote directly electing a candidate in their constituency (of which there are 299) via a first-past-the-post ballot; the second is a vote for a party’s electoral list. The ‘list’ vote sees 331 further members elected, totalling 630 members in the next Parliament.

Secondly, there are thresholds that a party must clear in order to win Bundestag seats – either, winning three separate constituencies via first votes, or by obtaining 5% of the nationwide second vote.

These electoral nuances make determining a potential election result, as well as the possible coalitions which could be formed after such a vote, difficult, as the number of parties in the new Bundestag could be as low as four, or as high as eight, depending on how the plebiscite actually pans out.

Coalition Possibilities

In any case, several parties have imposed a ‘cordon sanitaire’, and already ruled out certain possibilities. For instance, all major parties have refused to form a coalition, or co-operate in any way, with the AfD, while parties including the CDU, SPD, Greens and FDP have all refused to form a coalition which includes the BSW. Furthermore, a repeat of the present ‘traffic light’ coalition isn’t seen as a desirable outcome by any of the parties which have been involved in the most recent government.

Assuming that opinion polling is correct, the CDU/CSU is likely to lead the next German government, holding a large lead over other parties contending the election. The number of parties that the ‘union’ would need to join forces with to make a workable majority is uncertain, though a ‘grand coalition’ of the CDU/CSU and SPD seems the most plausible outcome, albeit one that is unlikely to feature Olaf Scholz in its cabinet, given Marcus Soder’s (CSU leader) opposition to such an eventuality.

Were another party to be needed in order to achieve a workable majority, the FDP are the most likely candidate to join the government, as was seen during Merkel’s second government from 2009-2013. This, however, would require the FDP to clamber over the aforementioned 5% polling threshold.

Perhaps the biggest potential curveball would be if support of the Greens were required in order for a CDU/CSU-led coalition to achieve a stable Bundestag majority, with both parties having indicated on numerous occasions that it would likely be tough for the two to come to an agreement at the present time. Such an eventuality is one which is likely to lead to the most prolonged, and tumultuous, post-election coalition negotiations.

Macro

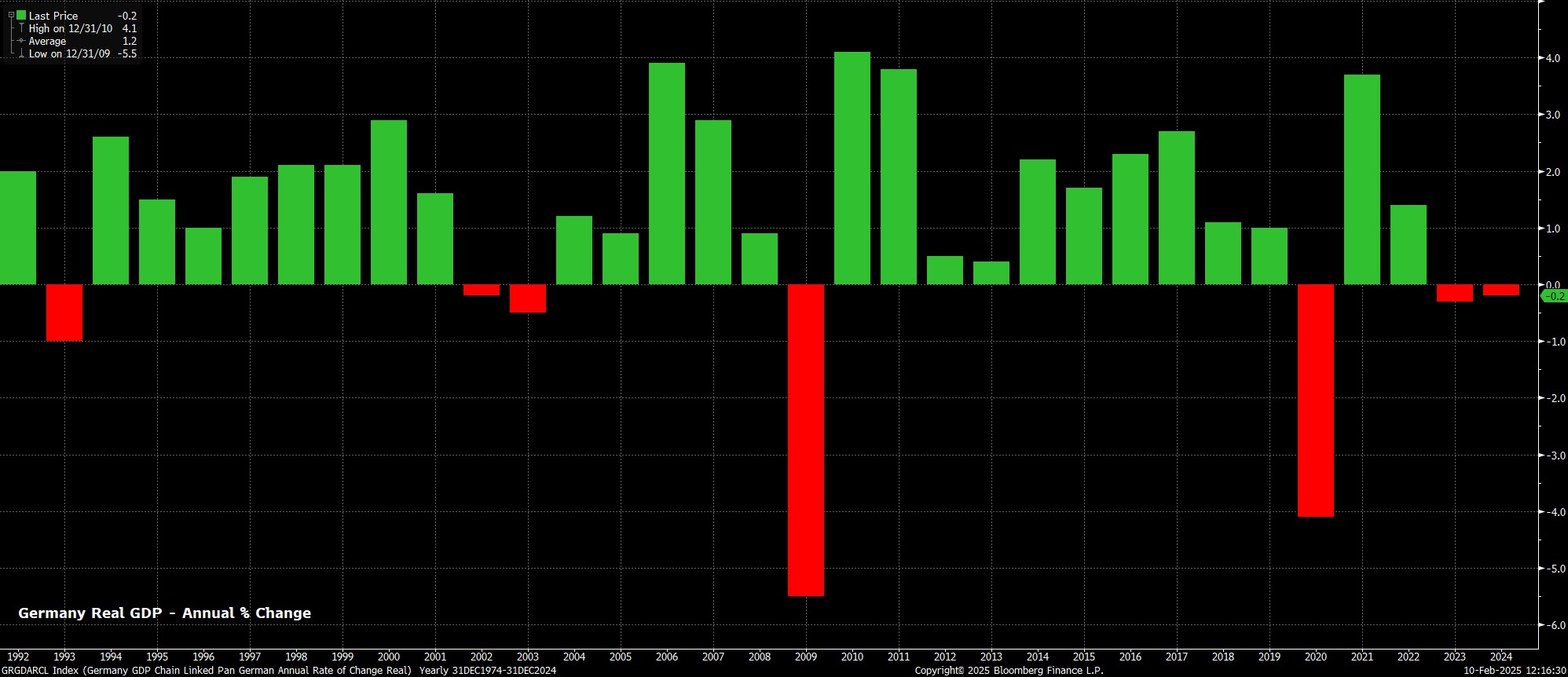

Whatever coalition ends up being formed after the February election, the incoming government will have an extremely difficult task on their hands, inheriting an economy which has seen GDP contract for two years in a row.

Increasingly, Germany’s long-running economic issues appear structural in nature, with ‘quick fixes’ highly unlikely. While parties have proposed numerous measures to tackle these woes, including tax reforms, and deregulation, these proposals will take time to materialise, and even longer to have a discernible impact in terms of improving the macroeconomic outlook. Hence, any near-term positive growth impact is likely to come from an alleviation of pre-election uncertainty upon formation of a coalition, which could provide a short-term boost, were it to unleash an increase in investment post-election.

The other significant issue on the table is the potential for reform of the German ‘debt brake’, enacted in 2009, which restricts the annual deficit to 0.35% of GDP. Consensus leans heavily towards the ‘debt brake’ being reformed at some stage during this parliament, though there seems to thus far be little clarity as to how potential coalition members may seek to reform such a measure. This, hence, is likely to be a topic that features heavily in negotiations to form the next government.

That said, reforming the ‘debt brake’ is easier said than done. To do so requires a two-thirds majority in both the upper and lower chamber of the German parliament, which is currently lacking. Furthermore, even if the brake were to be reformed in some way, Germany is likely to run into EU fiscal constraints in relatively short order, meaning the amount of additional borrowing that could be gained is likely to be relatively small. While countries such as France and Italy have, largely, ignored the EU’s clamour for adhering to the bloc’s fiscal rules, Germany seems much more likely to abide by those rules.

Markets

For financial markets, the key short-term consideration will be how long it takes for a coalition to be formed and whether, as most presently assume, such a coalition is headed by the CDU/CSU in the form of Friedrich Merz. Were a new government to be announced in short order, the election could well prove to be something of a non-event for European assets.

In terms of equities, it is important to remember that only around 20% of the DAX is domestically exposed, with the benchmark index having a significant international tilt to its composition. Hence, barring any electoral shocks, the market’s main focus is likely to remain on the potential of a tit-for-tat US-EU trade war, and the associated adverse impact that could be felt on the eurozone economy at large.

Meanwhile, for the EUR, the most significant risk is that coalition negotiations become prolonged, with the typical correlation between heightened political uncertainty, and a weaker currency, likely holding true once again. Despite that, it does seem that the common currency has now passed the point of ‘peak pessimism’ with an adequate degree of bad news having already been discounted. Hence, were a coalition to be formed relatively quickly, a subsequent upswing in investment, and German economic activity, could provide a modest tailwind for the currency.

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.