- English

- 简体中文

- 繁体中文

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- Español

- Português

- لغة عربية

Analysis

Parallels From Prior Engineered Economic Slowdowns

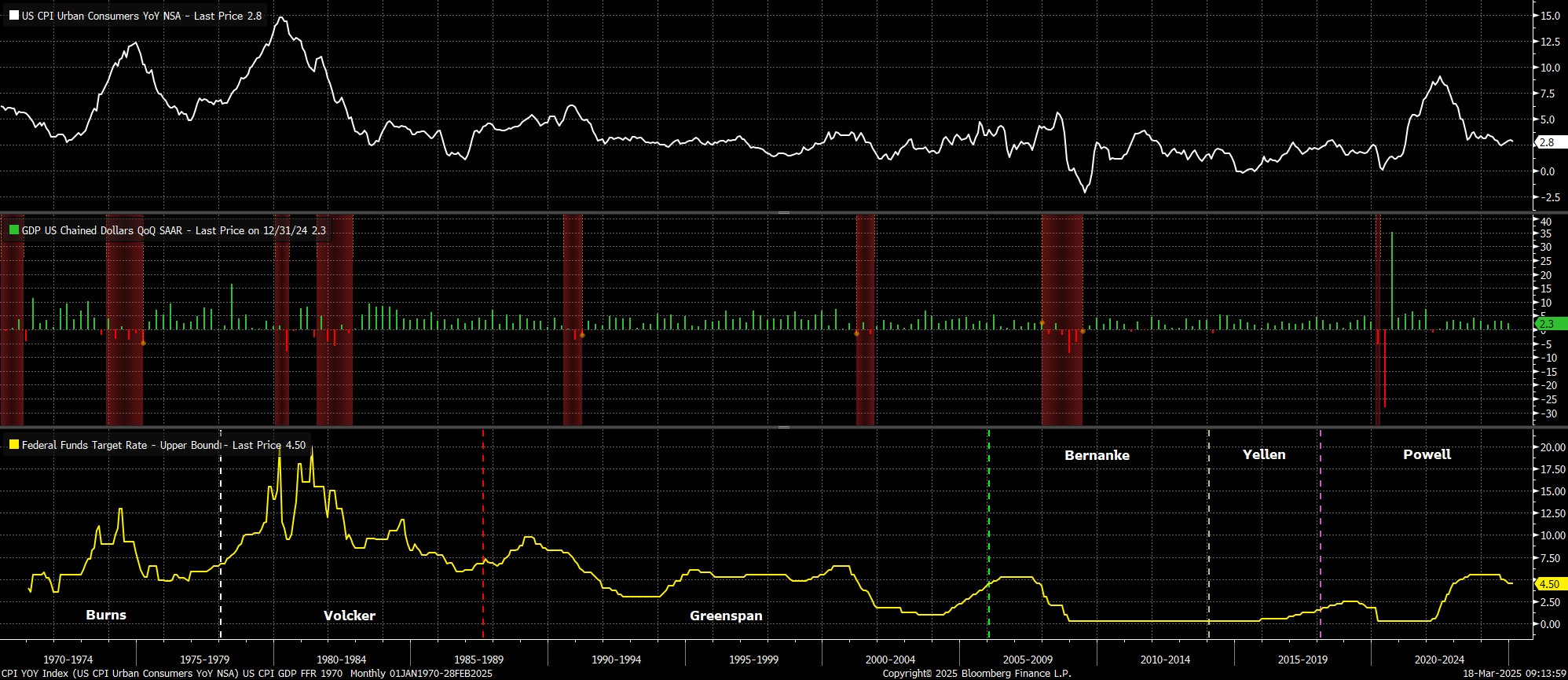

Since 1970, the US has, per the NBER, experienced a total of 8 recessions. Of those, only two can reasonably be considered as having been ‘engineered’, and somewhat deliberate. Those two, of course, came in the early-1980s, as part of the ‘Volcker shock’, whereby the eponymous Fed Chair brought an end to soaring inflation, and inflation expectations.

Volcker did this via the rather blunt instrument of interest rates, raising the fed funds rate as high as 20% in 1981, in an aim to sharply reduce the money supply (monetarism was a thing back then!). In turn, these efforts stamped down on demand within the economy, slashing spending among consumers, and sending business investment tumbling, as the cost of borrowing surged.

It actually took Volcker two attempts at this process to achieve the desired effect, and to spark a substantial decline in inflation. After the US entered recession in 1980, the fed funds rate begun to fall, giving price pressures a ‘second wind’. Cue, subsequently, a renewed effort to tighten monetary policy, and a sixteen month long second Volcker recession to finally eradicate stubbornly high inflation. Price pressures, subsequently, remained contained, until this cycle, when inflation surged in the aftermath of the pandemic – on which, more later.

The reason for this mini economic history lesson is that we are able to draw some parallels from the Volcker recession, to the present day economic agenda seemingly being followed by the current occupant of the White House, President Trump. While parallels, clearly, can’t be drawn between the economic acumen of the two involved, both appear to share a common aim – engineering an economic slowdown, albeit for considerably different purposes.

In the case of the legendary Fed Chair, Volcker realised that the only way to re-establish price stability would be to cause a significant degree of pain in the short-term, for the benefit of the long-term. As one of his successors at the Fed, Ben Bernanke, put it, Volcker “personified the idea of doing something politically unpopular but economically necessary”.

Turning to the present day, it appears that President Trump has flipped that quote on its head, in ongoing efforts to slash the size of the Federal Government, half the US’ budget deficit, and reallocate economic resources away from the public sector, towards the private sector. In short, a concept that is politically popular, but not strictly economically necessary.

The political attractions of such a strategy are clear. President Trump, and the GOP, won a thumping mandate in November’s election, winning not only the electoral vote, and the popular vote, but also retaining control of the House, and flipping control of the Senate. Furthermore, knowing that this ‘reprivatisation’ process will not be easy, and will likely inflict severe economic pain, there is political expedience in doing so sooner rather than later, at a time when said pain can be blamed on those in the prior Administration, and before attention shifts to next year’s midterms.

This brings me on to another parallel with past recessions – that of the pandemic, around five years ago. To be clear, this was not an engineered recession, but a necessary one, whereby economies around the world were put into a ‘deep freeze’ amid the imposition of ‘lockdown’ measures to contain the spread of the virus. This freeze was enabled not only by DM central banks slashing rates to the lower bound once again, but also by a range of innovative fiscal policies, designed to limit the detrimental effects of lockdown as much as possible, and to ensure as rapid as possible an economic recovery.

One thing that the pandemic made clear, though, is that it is much easier to shut down an economy, than it is to start it back up again. In fact, even half a decade on, we are still dealing with the consequences.

For example, the inflationary hangover from 18 months of fiscal largesse and uber-easy monetary policy was clear for all to see, with price stability yet to have been fully restored in most DM economies. Furthermore, employment in a number of sectors is still below its pre-covid peak, while the fiscal backdrop remains perilous on both sides of the Atlantic, even before one considers structural economic shifts which continue to pan out, such as a reduction in the frequency of eating, and drinking, out.

Once again, the current situation is not a precise ‘carbon copy’ of what has happened recently, but the pandemic provides some useful lessons as to the unintended consequences that can be brought about from deliberately bringing an economy to a halt.

As a result, we currently stand at an interesting, and delicate, juncture. If – and it’s a big ‘IF’ – the Trump Administration can indeed successfully pull off this re-allocation of economic resources, shoring up the US’ fiscal footing in the process, then the long-term bull case for the economy, and by extension the equity market, becomes an incredibly strong one, particularly if a few Fed cuts are thrown in too.

However, as history has taught us all too many times, what seems like a simple and plausible idea on paper, is much more difficult to pull off in practice, particularly in a global economy as inter-connected as today’s, and one which continues to be buffeted by protectionist trade policies.

In the short-term, we seem set for a rocky ride ahead; we must hope that the promised long-term gains do eventuate, and that supply side reforms trump demand side turbulence.

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.