- English (UK)

Trump’s $200B MBS Purchase Plan: Short-Term Housing Rally, Long-Term Risks Amplified

.jpg)

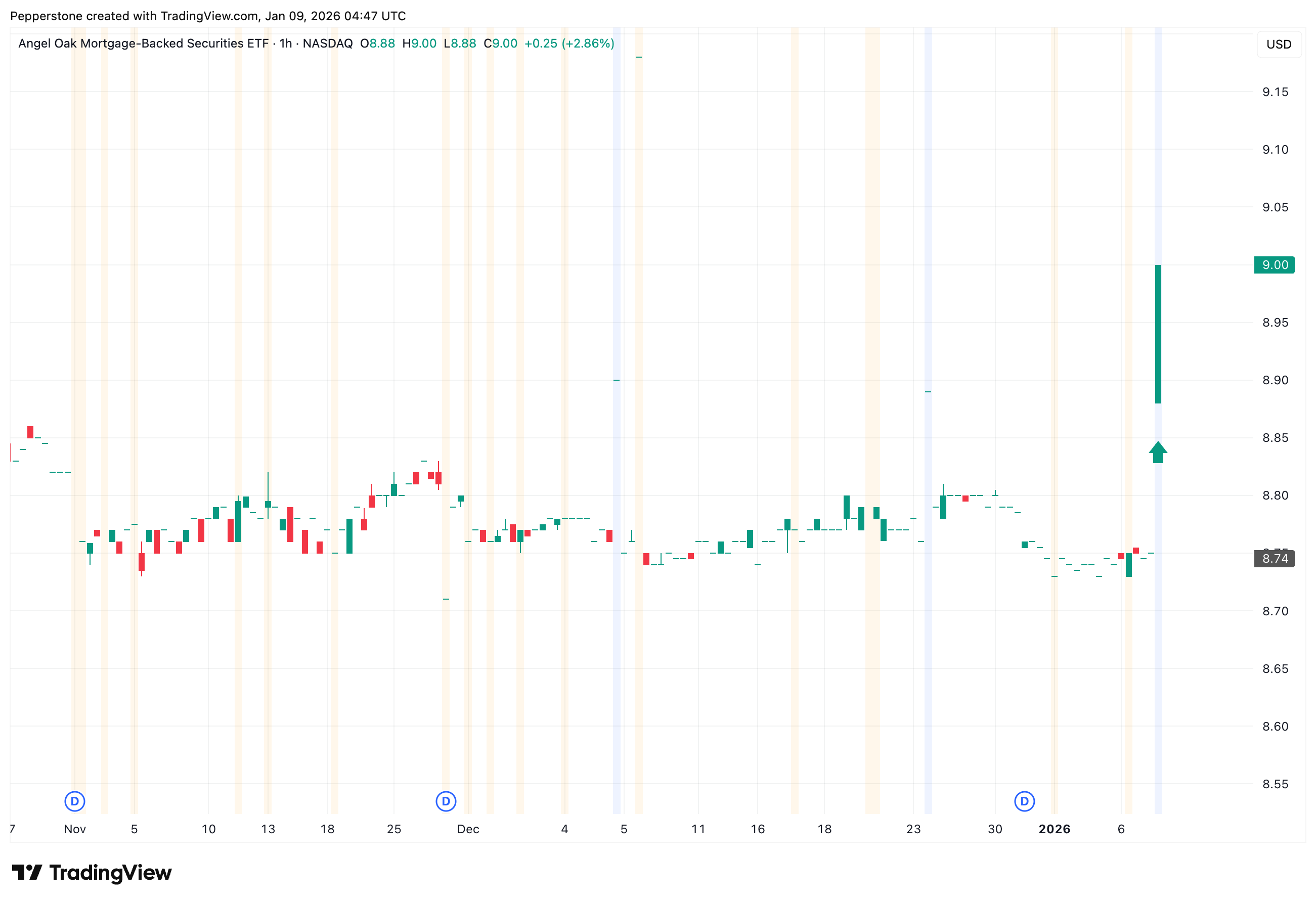

U.S. President Donald Trump on Thursday (January 8) announced that he has instructed representatives to push government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) — Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac — to implement a $200 billion mortgage-backed securities (MBS) purchase program. The aim is to reduce mortgage rates, lower monthly payments, and improve housing affordability.

The market reacted immediately: MBS prices rose, real estate-related stocks and interest-rate-sensitive assets rebounded, and long-term yield volatility increased significantly.

However, this is not merely a “housing rescue” policy. It functions more as an interest-rate expectation trade leveraged by implicit government guarantees. The move is supportive of rates and risk assets in the short term, but in the medium term, it may amplify volatility rather than reshape market trends.

Market Context: The Housing System Struggles Amid High Mortgage Rates

Over the past two years, the U.S. housing market has been under continuous pressure. Following the pandemic, the Fed raised rates rapidly, pushing 30-year fixed mortgage rates close to 7%. According to Freddie Mac, although rates fell slightly to around 6.2% last week, they remain well above pandemic-era levels.

High rates have directly raised the barrier to homeownership, hitting first-time buyers the hardest. At the same time, “rate locks” have led many existing homeowners to retain low-interest loans, suppressing secondary market supply. The result: demand exists, but transactions cannot flow smoothly, creating clear structural bottlenecks in the housing market.

Against this backdrop, Trump’s push for a large-scale MBS purchase has a clear intent — bypass traditional fiscal channels and address housing pressure directly via interest rates, using a faster, lower-political-cost approach while buying time in the election cycle.

Policy Logic: Not QE, but Almost QE

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are technically market-based entities, but they have been under the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s (FHFA) conservatorship since the 2008 financial crisis. Their core function is to buy mortgages from banks, package them into MBS, sell them to investors, and provide implicit government credit support.

Under the current plan, GSEs would expand their holdings of MBS, keeping around $200 billion on their balance sheets rather than selling all newly issued MBS into the market. The transmission mechanism is straightforward:

- Larger retained holdings → reduced MBS supply in the market

- Relative demand rises → MBS prices increase, yields fall

- Banks price new loans off MBS yields → mortgage rates decline

This is not a direct Fed operation and, strictly speaking, is not quantitative easing (QE). But in terms of market impact, it similarly lowers long-term borrowing costs by increasing bond demand, producing short-term effects comparable to QE.

Dollars, Rates, and Capital Flows: How the Policy Could Transmit

When policy directly pushes down long-term rates, the impact extends beyond housing, propagating along the yield curve to dollar assets, risk appetite, and global capital flows.

- Rates and the Dollar: Reduced Attraction

Large-scale MBS purchases could exert downward pressure on long-term rates, flattening the yield curve in the near term and narrowing the U.S. asset yield advantage.

Against a backdrop of the Fed still on a rate-cut path and global capital searching for returns, this structural rate suppression may mildly weaken the dollar. Conversely, some non-dollar assets — such as emerging-market bonds and high-yield credit — could benefit if risk appetite improves.

That said, this does not mean the dollar will enter a clear downtrend immediately. Geopolitical risks, global safe-haven demand, and the dollar’s safe-haven status remain. In the short term, the dollar is more likely to drift weaker with volatility rather than fall in a one-way trend.

- U.S. Stocks and Housing Sector: Rate Expectations Lead Pricing

After Trump’s announcement, real estate-related assets responded first: for example, Rocket Companies and loanDepot shares surged, and homebuilder stocks priced in the news positively.

This shows the market’s rapid adjustment to lower-rate expectations. Even if actual housing demand has not improved significantly, assets react as soon as financing conditions are perceived to be loosening.

- Extension of Fed Policy Transmission

While not Fed-driven, this plan mirrors past easing cycles, reinforcing perceptions of broadly accommodative policy. If long-term rates continue falling, market expectations of future rate cuts can themselves influence bond and risk asset pricing.

It is important to note that these expectations rely heavily on sustained policy execution. If the market doubts the scope or regulatory flexibility of the program, prices may adjust ahead of actual policy moves.

Risks and Constraints: No Free Lunch

From the perspective of lowering “cost of living,” the plan offers clear short-term benefits, but medium-term risks remain substantial.

First, execution and regulatory constraints. Expanding GSE-held MBS leaves more risk on government-backed balance sheets. As of October 2025, their retained assets were already up roughly 25% from prior levels; adding $200 billion more approaches regulatory tolerance limits. If the FHFA cannot or will not loosen constraints further, the plan’s effectiveness could be limited.

Second, structural issues persist. Even with lower rates, supply constraints will not automatically ease. If demand is stimulated but supply cannot respond, home prices may remain pressured, undermining affordability goals.

More importantly, artificially low rates tend to encourage higher leverage. If the economic cycle reverses, highly indebted households face amplified risk, potentially returning to the “implicit guarantee → risk accumulation → policy backstop” cycle.

Focus on the Gap Between Policy and Reality

Overall, this $200 billion MBS purchase plan functions more as a short-term policy stimulant. It may reduce some households’ monthly payments by hundreds of dollars in 2026, or deliver political benefits in key swing states. But the cost is a U.S. housing finance system increasingly tilted toward “too big to fail” and implicit guarantees.

For traders, key points to watch include:

- Will the FHFA raise the GSE retention limit?

- If yes, interest-rate trades could remain supported

- Can 30-year mortgage rates drop meaningfully below 6% in Q1?

- If not, housing rebound could fade quickly

- Will complementary policies (e.g., bans on institutional single-family purchases) actually take effect?

The gap between policy logic and market reality may create trading opportunities, but also marks a critical juncture for risk management.

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.