- English (UK)

Summary

- Dour Outlook: A rapidly weakening labour market, coupled with mounting political uncertainty, and ever-present fiscal risks, makes a grim mix for the UK economy

- Dovish BoE: However, all that, coupled with embedded disinflation, has seen the BoE turn dovish, with a March cut now on the cards

- Downside Risks: Risks for the GBP, though, continue to tilt to the downside, especially in the crosses, while fiscal pressures should weigh on the long-end of the Gilt curve

Those wanting some good news should probably read another note, as this one doesn’t contain much on that front.

The UK economy is, to put it somewhat politely, in a very bad way; and, things seem likely to get worse, before they get better. The same applies to both the quid, and Gilts.

Labour Market Rolling Over Rapidly

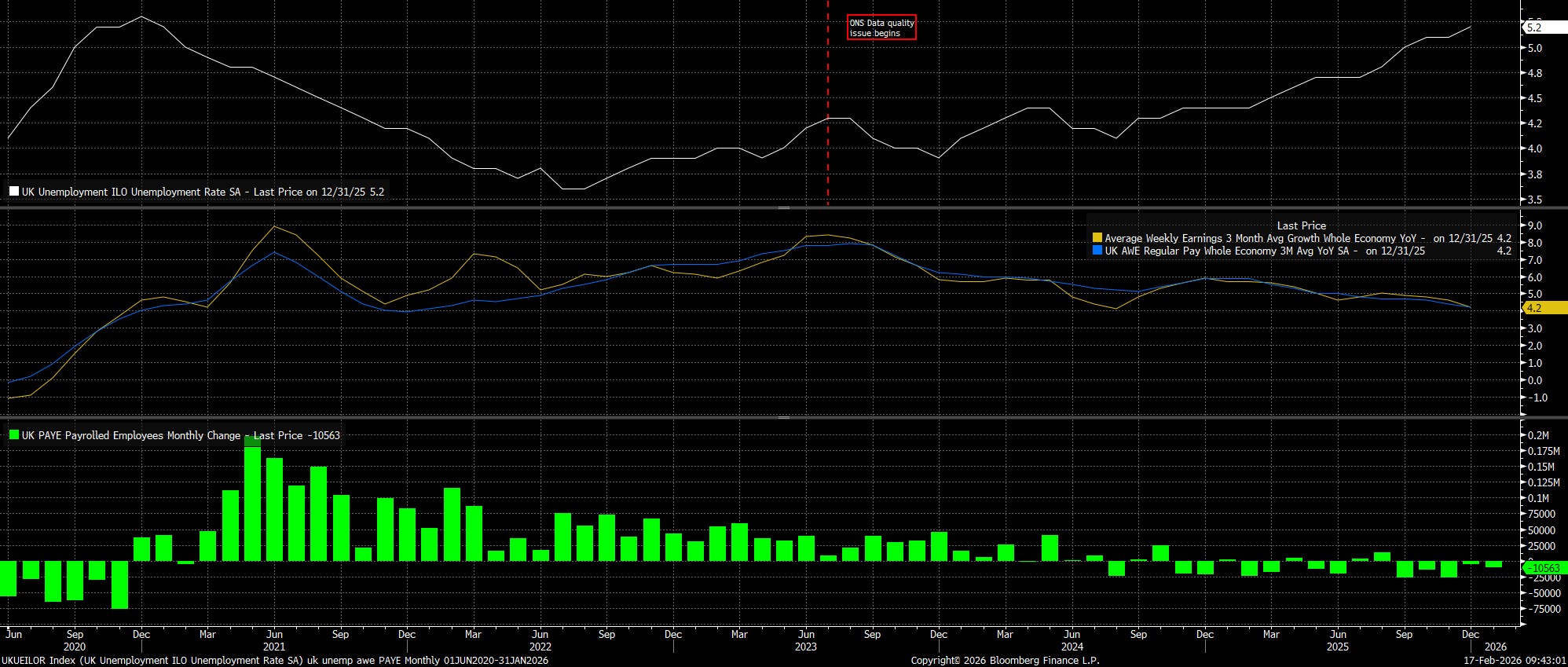

The labour market, firstly, is not only faltering, but at this point seems to be falling off a cliff. Unemployment rose further to 5.2% in the three months to December, a fresh cycle high, while PAYE payrolls fell for the fifth straight month in January.

Both of those, to be clear, stem directly from policy choices made in Westminster. Not only has the cost of hiring been increased, with the minimum wage now at two-thirds of the median salary, up from around half in 2000, but the risk associated with hiring has also been markedly increased as a result of the Employment Rights Act. In addition, work itself has been increasingly disincentivised as a result of various benefits uplifts. This, quite clearly, creates a very messy policy mix, with predictable consequences that are now playing out – even if it seems nobody on Whitehall was able to see those consequences coming.

Inflation Is Heading Back To Target Soon

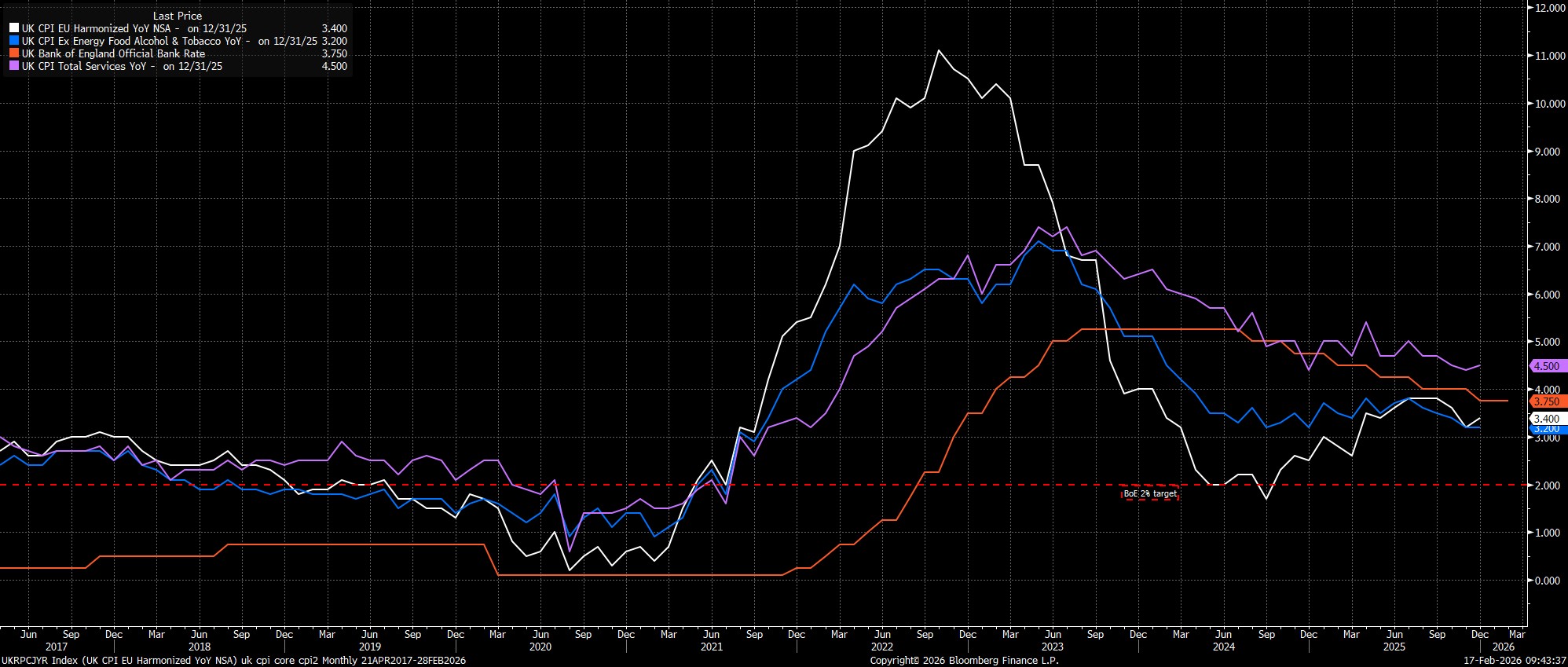

This increased margin of labour market slack, naturally, provides a strong disinflationary impulse, strengthening the case for headline inflation to return to the Bank of England’s 2% target by the spring.

Such a case is further supported by a host of other factors, including an easing in energy inflation stemming from policies announced in last November’s Budget, more favourable seasonality in terms of transportation costs, a disinflationary base effect in the education sector, and a further easing in price pressures in the services sector. Add all of this together, and throw on top the food disinflation seen in Europe making itself known on this side of the Channel, and you get a recipe that takes you to, or below, 2% by Q2 26. Then, the lack of any labour market tightness whatsoever keeps you at that 2% target for the foreseeable future, barring any surprise external shocks.

The BoE Have Made A Dovish Pivot

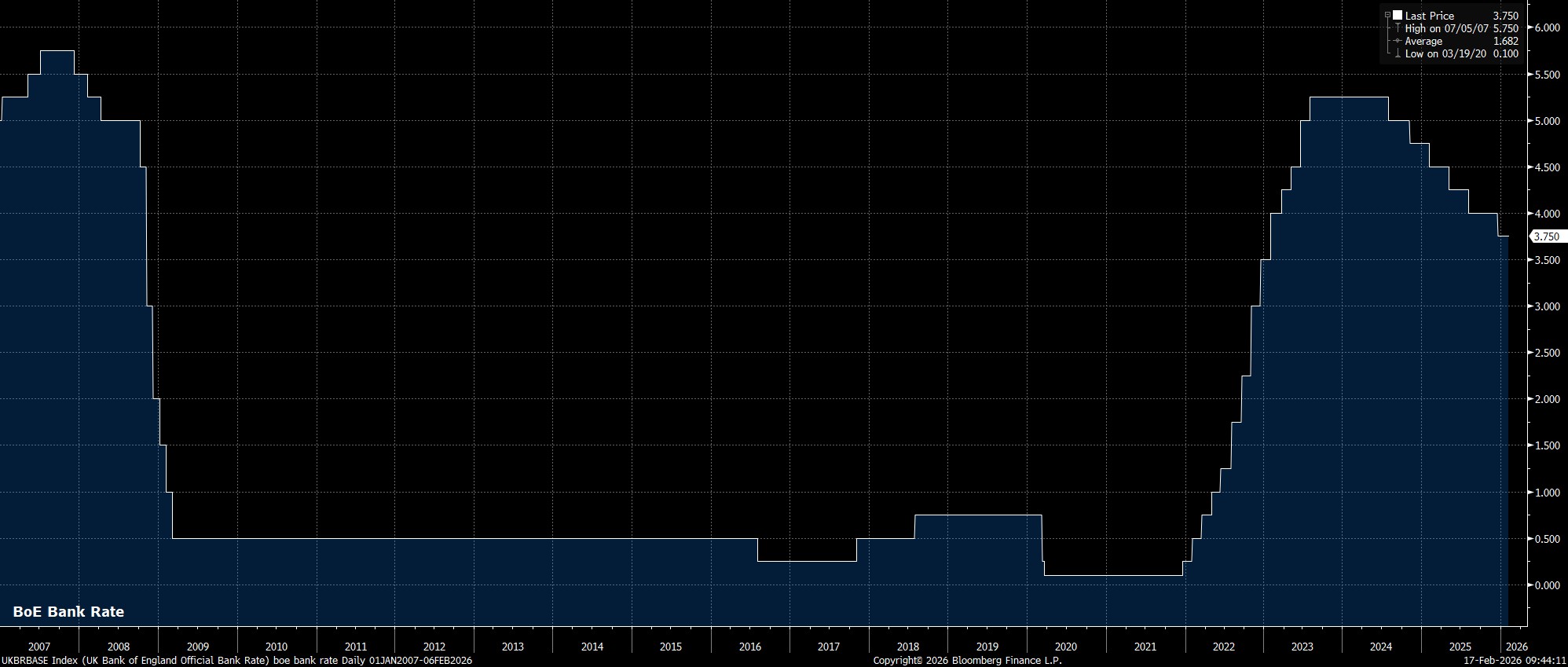

With those two factors in mind, it should come as no surprise that the BoE have made a significant dovish pivot since the start of the year. The February MPC confab brought a triple-whammy of dovishness – where the tightest possible vote split, and explicit guidance nodding towards future cuts, were combined with economic forecasts broadly in line with the aforementioned inflation path.

Consequently, a 25bp cut at the March meeting now seems to be on the cards, with further easing set to be delivered beyond then, as Bank Rate returns to a neutral level, around 3%, by the end of summer. At some stage, potentially relatively soon, the MPC’s hawks (e.g. Pill, Greene, etc.) will have to eat some ‘humble pie’, and admit that their fears over inflation persistence are misplaced.

Fiscal Risks Are Mounting Again

But, wait, there’s more. Not only is the labour market weakening at a rate of knots, disinflation embedded, and the BoE turning dovish, but the fiscal outlook continues to give cause for concern.

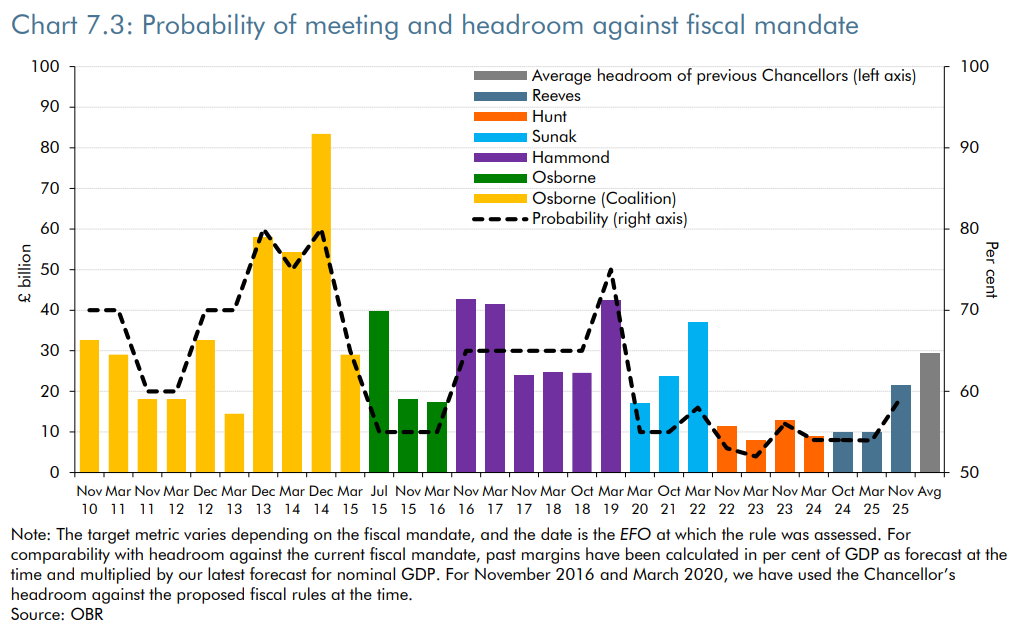

In the ‘here & now’, while the Chancellor did more than double fiscal headroom to £22bln in the November Budget, the details of the OBR’s forecasts don’t paint anywhere near as rosy a picture of the public finances. As noted at the time, the key issue with the Budget is that the various spending increases are all front-loaded, while the tax increases to fund that spending (primarily extending the freeze in income tax thresholds) are all back-loaded. In short, this means that spending is all-but-guaranteed to increase, while pledges to hike taxes in the year of the next general election simply do not seem credible.

If that wasn’t bad enough, the febrile political backdrop in Westminster means that a change in the Labour Party leadership, and by extension a new Prime Minister, seems increasingly likely at some stage this year. While my working assumption is still that Keir Starmer will muddle through until the May local elections, and that a leadership challenge will soon follow what is likely to be a calamitous result in that plebiscite, the timing of a leadership change isn’t really the biggest issue.

That, is the fact that whoever replaces Starmer as PM is likely to adopt a fiscal policy significantly to the left of that which the Government are currently running. This is largely a result of the Labour membership, who are the electorate to which one must appeal in a leadership election, favouring traditional ‘tax and spend’ policies, which any potential leader would have to endorse in order to come out on top in a contest. As such, one of the new Chancellor’s first acts upon arriving in Downing St would likely be to rip up the current fiscal rules, increase public spending even further, raise the tax burden to fresh record highs, and likely ramp up Gilt issuance too.

Amid all of that, it should come as no surprise that risks to the broader growth outlook continue to tilt firmly to the downside. While some leading indicators, such as the January PMI surveys, have surprised in the opposite direction, it seems highly unlikely that any positive momentum can continue for a prolonged period, amid a further ramp-up in political uncertainty, and considering the parlous state of the labour market, along with the negative demand implications that that will bring with it.

Risks For UK Assets Tilt To The Downside

For UK assets, all this points to significant downside risks, most notably for the GBP, and for long-end Gilts. That GBP weakness is likely to be most obvious in the crosses, with a continuation of the ‘sell America’ trade probably keeping something of a lid on any cable declines for the time being. Meanwhile, long-end Gilts will soon need to price both renewed political uncertainty, and greater fiscal risks, neither of which are conducive to upside. That said, the curve as a whole should steepen, with the more dovish near-term BoE outlook giving room for the front-end to gain ground.

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.