- English (UK)

Geopolitical Risk in 2026 Is Rising and Markets May Be Underpricing It

Despite this, broad financial markets appear unaffected and move into 2026 with the risk bulls in control – but many do raise the question of whether geopolitical risk in 2026 is currently underpriced.

Major Geopolitical Events Shaping Early 2026

Market attention has been dominated by two recent developments, which hold significant global implications.

The first is the US military capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and the subsequent assertion of control over Venezuela’s oil reserves. The second is the sharp escalation in diplomatic tensions between the United States and Denmark over Greenland, alongside signals that the US intends to exert greater strategic influence over the territory.

Talks between the US and Denmark are set to play out, and while a deal of sorts is the markets base case, what happens from here, and what is means for US-NATO relations will be key.

US Strategic Objectives and Domestic Political Considerations

Actions taken by the Trump Administration appear focused on strengthening the United States’ strategic geographic positioning from a military and security perspective. These moves also reinforce the US’s role as the dominant global power at a time of increasing multipolar competition.

Domestically, geopolitical strength and decisive foreign policy action may also support Trump’s approval rating leading into the US mid-term elections. Of course, Trump’s presidency is in play here, but he would be hoping a lift would resonate with the Republican party’s prospects, particularly in the House vote.

Trump’s approval rating

Execution Risk and the Case for a Higher Risk Premium

These geopolitical strategies carry substantial execution risk. Even a low probability of military confrontation, policy miscalculation, or escalation error justifies a higher geopolitical risk premium across asset classes.

History shows that when geopolitical risk crystallises, market reactions tend to be swift, nonlinear, and highly correlated, particularly across equities, currencies, energy markets, and volatility.

Global Defence Spending Signals a Structural Shift

Rising geopolitical tensions are increasingly reflected in global defence spending. In the United States, President Trump has proposed a defence budget of $1.5 trillion for 2027, representing an increase of approximately 60 percent compared with approved 2026 levels.

Germany has lifted its defence budget to €108 billion, while Japan, Taiwan, and China have also significantly expanded military spending. This coordinated increase suggests governments are reassessing long-term security risks rather than responding to short-term political noise.

Financial Markets Remain Strikingly Calm

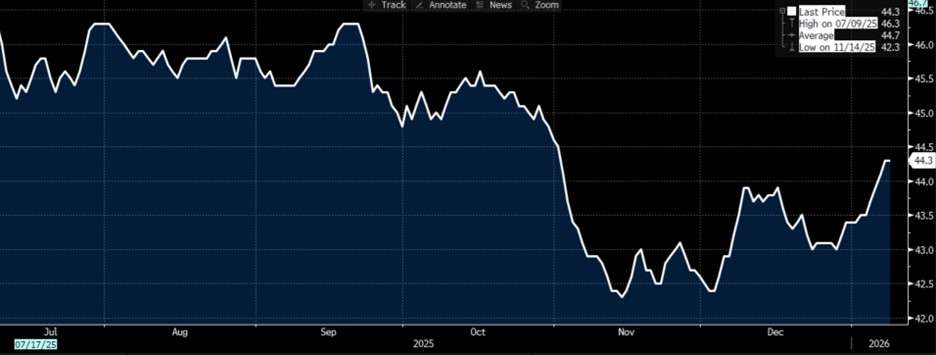

Despite the escalation in geopolitical risk, financial markets show limited signs of stress. The S&P 500 continues to trade at all-time highs, the US dollar is grinding higher, Brent crude has stabilised and rebounded from the $60 level, and 6- and 12-month S&P500 and FX implied volatility remains sanguine and below twelve-month averages.

S&P500 1-year implied volatility

Taken together, these indicators suggest investors are largely dismissing geopolitical headlines and see little immediate need to reduce exposure or increase tail-risk hedging.

Are Markets Acting as the Ultimate Guardrail?

One interpretation is that recent US actions have been deliberately calibrated to avoid destabilising financial markets. Under this framework, market stability and political approval act as constraints on how far geopolitical escalation can extend.

This view assumes that policymakers remain acutely aware of the feedback loop between markets, economic conditions, and political capital.

Other Geopolitical Flashpoints Markets Should Monitor

Beyond recent headlines, several ongoing geopolitical risks remain critical for investors in 2026. These include tensions between China and Taiwan, the war between Russia and Ukraine, instability involving Iran and Israel, internal unrest in Iran, and rising domestic tensions in the United States linked to immigration policy and civil unrest following the fatal shooting of Renee Good in Minneapolis.

Each of these risks carries the potential to shift market probabilities rapidly.

Why Markets Often Misprice Geopolitical Risk

Markets have historically struggled to price geopolitical risk in advance. Investors tend to prefer reacting once outcomes become clear rather than positioning for uncertain scenarios. The prevailing assumption appears to be that tensions will rise rhetorically without escalating into worst-case outcomes.

However, this approach leaves markets vulnerable to abrupt repricing when the perceived probabilities change.

Why Geopolitical Risk May Be Underpriced in 2026

Markets are dynamic, and shifts in geopolitical risk are rarely linear. When perceptions change, repricing tends to be fast, disorderly, and cross-asset in nature. There is growing concern that markets are underestimating the risk of a more fractured US–NATO relationship or a policy miscalculation related to Greenland with broader strategic consequences.

A More Uncertain Global Landscape for 2026

While the full impact of these developments remains uncertain, one conclusion is already clear. Geopolitical risk in 2026 has increased materially, even before considering other major macroeconomic risks such as monetary policy, debt sustainability, and global growth uncertainty.

Markets may not be pricing that reality yet.

Welcome to 2026.

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.