- English (UK)

2026 US Macro Outlook: Returning To Policy Stability

Summary

- Policy Stability: The Trump Admin's fiscal, regulatory, trade, and immigration policies are likely to be little changed in 2026, allowing markets to benefit from policy stability

- Fed Easing: Further Fed cuts remain on the cards, though a move below neutral seems unlikely barring material labour market weakness

- Goldilocks Re-Acceleration: Greater policy clarity should permit a re-acceleration in labour market conditions, as price pressures continue to fade, and the risk of inflation persistence eases

The words ‘trade’, ‘Trump’ and ‘turbulence’ pretty accurately sum up how the US economy has evolved over the course of the last year, though by and large the private sector has succeeded in ‘muddling through’ despite a huge amount of uncertainty clouding the outlook. Said uncertainty should begin to lift in 2026, with the Trump Admin’s policy approach now largely set, and with the FOMC set to continue to remove policy restriction, as the fed funds rate falls back to a neutral level.

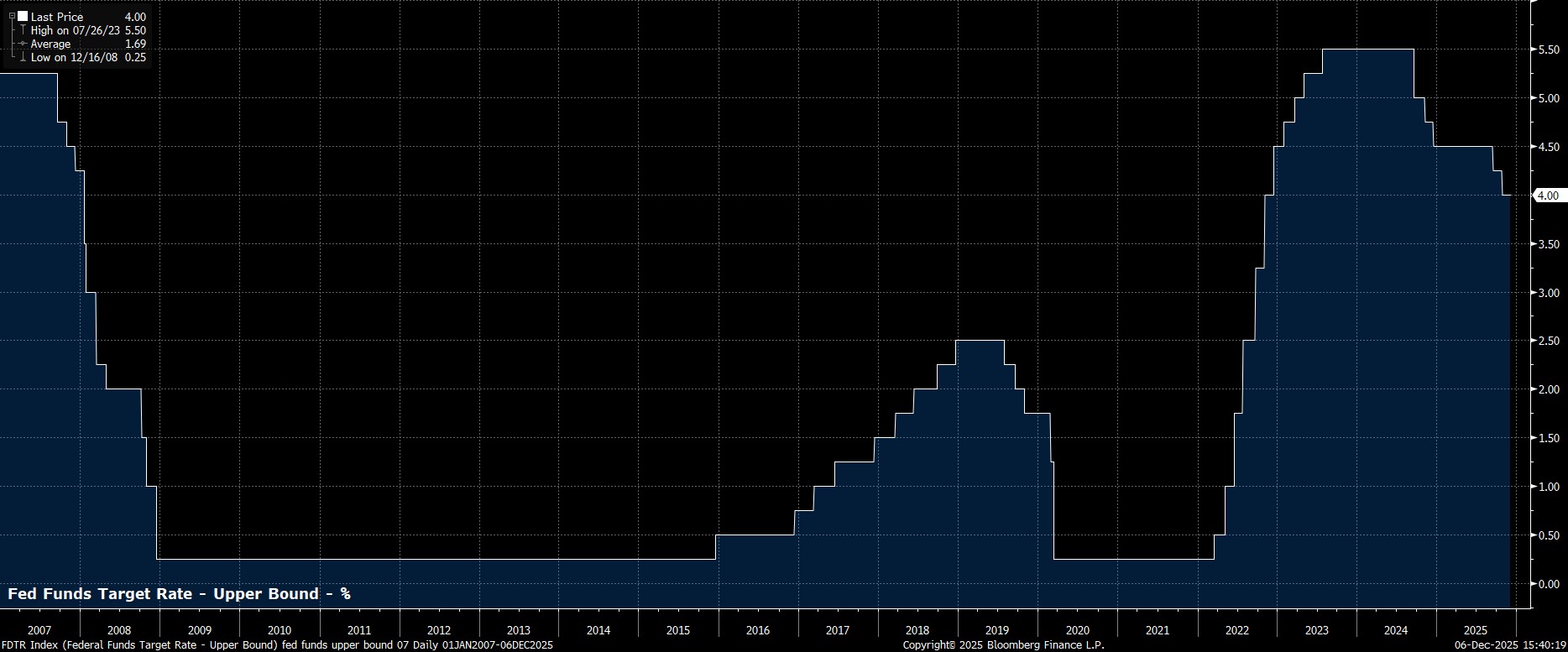

Further Fed Cuts To Come

Having already delivered two 25bp cuts in September and October, plus with another such cut likely to be delivered at the December meeting, it seems plausible that the FOMC are approaching the stage where a majority of policymakers view present downside risks to the labour market as having been adequately managed, permitting a shift to more of a ‘meeting-by-meeting’ policy stance next year.

That said, the direction of travel for the fed funds rate clearly remains lower, with the labour market continuing to take precedence over inflation in dictating the Fed’s reaction function, particularly considering that the impact of tariff-induced price pressures has not only been less than expected, but is also likely to prove temporary in nature. Consequently, as further labour market slack continues to develop through the first few months of the year, further cuts to the fed funds rate remain likely.

While these cuts will return the fed funds rate to a more neutral level, of roughly 3%, it is important to recognise that the FOMC’s two primary policy levers – FFR and balance sheet – are now working in tandem, and not against each other, as they have done for the last couple of years where, despite lowering the fed funds rate, balance sheet run-off ended up nullifying some of the loosening effect. Now, however, those two instruments are both set to move to a more neutral level (3% FFR & balance sheet at 20% GDP), with resumed balance sheet expansion – via the form of open market operations to ensure reserves remain ample – likely next year as well.

Fed Personnel In Focus

Of course, it shan’t simply be the near-term policy outlook that keeps Fed-watchers occupied in 2026, but personnel changes too.

The most obvious of these will be Chair Powell’s replacement, with all signs currently pointing to NEC Director Hassett getting the top job, even if a formal nomination seems unlikely until early-2026.

While, clearly, there are concerns over the further erosion of policy independence on the back of someone so closely aligned to Trump getting the job, it’s important to recognise that Hassett’s credentials (being a PhD economist & former CEA Chair) are not too dissimilar to those of his predecessors. Furthermore, unless there is a clear and cogent argument for enacting the uber-dovish policies, and sizeable rate reductions, that President Trump likely desires, then Hassett simply shan’t be able to garner the support of a majority of FOMC members to vote for such a move. The overall impact on the policy outlook, then, from a Hassett Chairmanship, would likely be limited.

In other personnel matters, there remain questions as to whether Powell will remain in his post as a Governor until the end of that term in 2028, or whether the end of his Chairmanship will also bring to an end his time on the Board. If the latter comes to pass, this opening would give Trump another chance to fill a spot on the Board of Governors. There is also the potential for an additional such opportunity, depending on how the Supreme Court rules in the ongoing case over the legality of Trump’s attempts to fire Governor Cook, on allegations of mortgage fraud, which she denies.

In addition to this, there is the matter of the regional fed banks, which the Administration appear to be increasingly focusing on. While the renomination of regional Presidents next February should proceed relatively smoothly, both Treasury Secretary Bessent, and the aforementioned Hassett, appear increasingly in favour of a requirement to force new regional bank chiefs to have lived in their district for a period of time, before taking up their posts. This will be a key theme to watch, even though the next enforced departures from regional banks (Barkin, Williams, and Daly) will not come until 2028.

K-Shaped Economy To Persist Despite Increased Policy Clarity

Though it has been derided in some quarters, the US economy has increasingly resembled a ‘K-shaped’ one in recent years, with a significant and marked divide having opened between those at the upper-, and lower-ends of the income spectrum. Such a divide is not only contingent on income from employment, but household wealth more generally, with both equity and property prices playing an increasing role in underpinning what remains an economy powered largely by consumer spending.

Whether due to a positive wealth effect, or another factor, the pace of consumer spending proved resilient throughout 2025, and should remain so in 2026, with copious amounts of corporate capital expenditure on technology (especially AI) providing the economy with a further boost.

Aiding both of those factors is a policy backdrop that, in contrast to the one seen this year, should prove considerably more stable, especially in the run-up to the midterm elections in November. Incidentally, those midterms are likely to lead to something of a ‘Trump put’ as we move through the year, with the President having extra incentive to not only ensure growth remains solid, but likely juice things further, in the run up to voters passing judgement on the Admin’s performance late in the year.

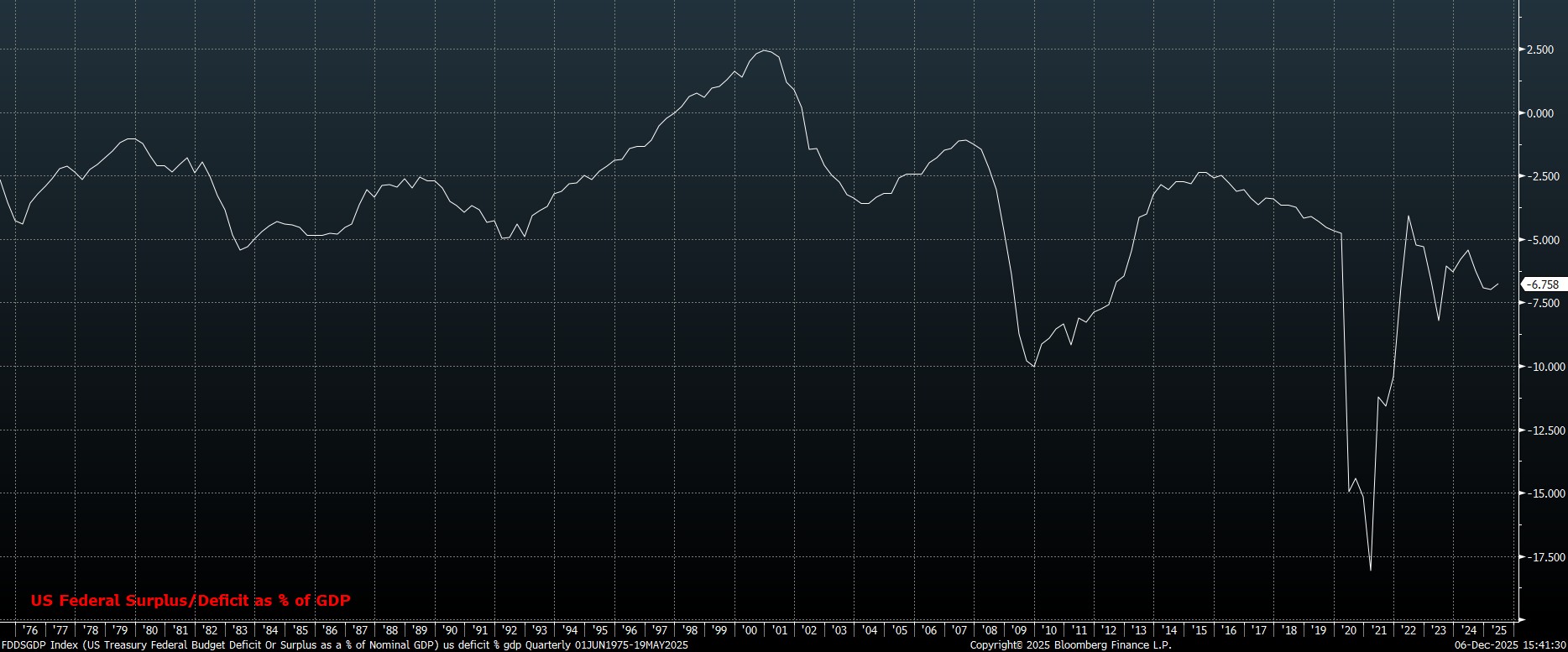

On that note, 2026 will see the fiscal loosening provided by the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill Act’ (OBBBA) finally start to take effect, with the significant tax reductions that the Act provides for likely acting as a strong tailwind for economic growth as the year progresses. The OBBBA does, however, also mean that huge budget deficits are going to become even more of a ‘norm’ than they have already, with it being essentially unheard of for the US economy to be running a 7% deficit outside of recessions. This, clearly, leaves obvious question marks as to the ability of fiscal policy to stimulate the economy as and when the next slowdown arrives, though that shan’t be a question that is answered next year.

Meanwhile, the Trump Admin’s policies in other areas have also become increasingly clear through 2025, and are unlikely to change significantly next year. Immigration enforcement, for example, will likely remain at the current high level, with a significant relaxation in the current policy stance unlikely, thus leading to continued constraints on the labour supply, and further lowering the breakeven pace of jobs growth.

Tariffs, finally, are also likely to remain in place, at an average rate of around 15%. While the Supreme Court may strike down Trump’s ability to implement tariffs under IEEPA, and possible refund payments would be a stiff headwind for Treasuries, there remain various other sections of trade law (e.g. 232, 301, etc.) which the Admin can, and almost certainly will, use in order to ensure that some form of trade levies remain in place. That said, a return to embargo-like tariffs, of the likes seen in Q2 25, seem off the cards.

Price Pressures To Fade Slowly

Speaking of tariffs, while inflation has clearly moved higher over the last twelve months, the inflationary impact of the Trump Admin’s trade policies has not proved as bad as had been initially feared. This likely owes to a few factors, including but not limited to the stockpiling and front-running that took place in the run up to ‘Liberation Day’, as well as the relatively rapid agreement of trade deals lowering the overall average effective tariff rate, plus firms absorbing a large chunk of the increase in prices, with some studies pointing to only around a third of the cost of tariffs having been passed on to the consumer.

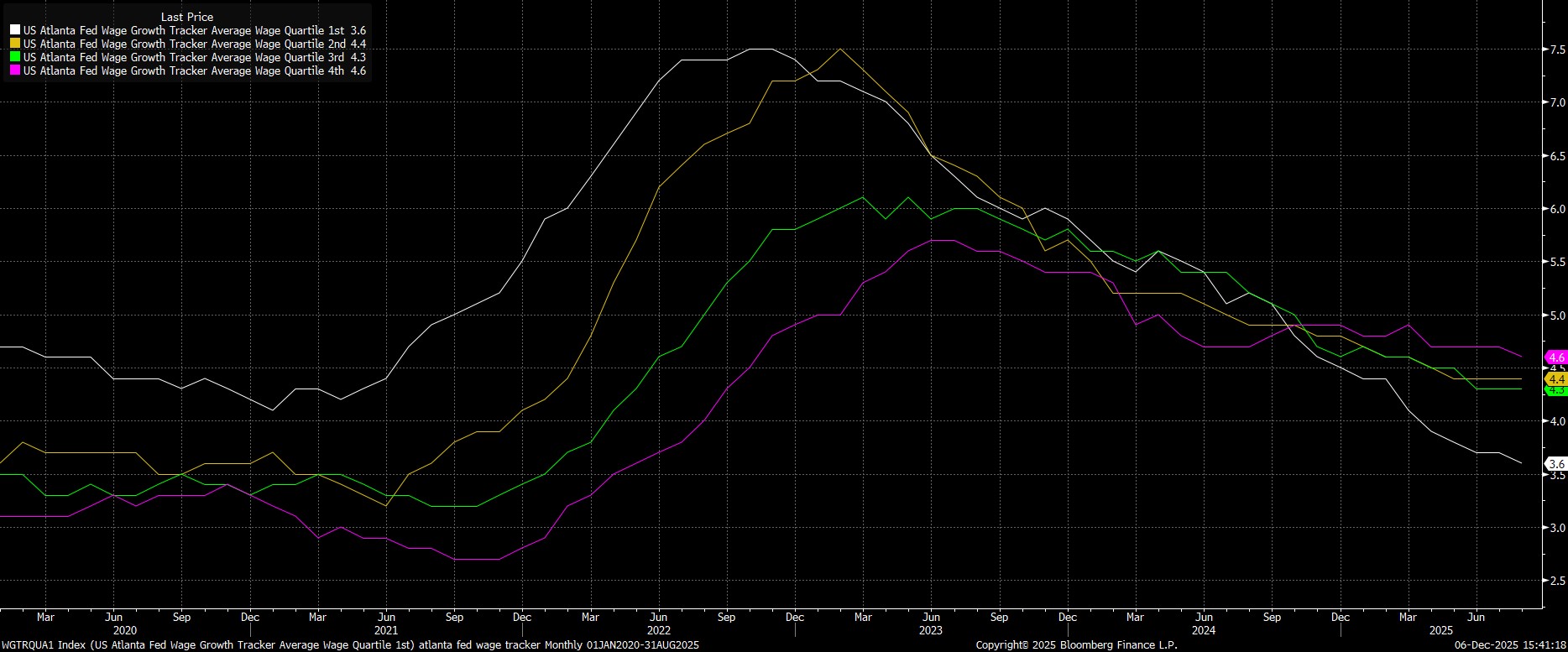

Taking all of that into account, and while further tariff-induced inflation is likely in the pipeline, rates of headline inflation (e.g. CPI and PCE) are likely to peak in the first half of the year, if not before. While the journey back towards 2% will not be a swift one, with the Fed’s inflation aim unlikely to be sustainably achieved until 2027, key areas of inflation persistence in the services sector have cooled notably over the last couple of quarters which, along with gradually looser labour market conditions, contributes to a notably reduced probability of price pressures proving particularly stubborn.

Labour Market Stasis Won’t Last Forever

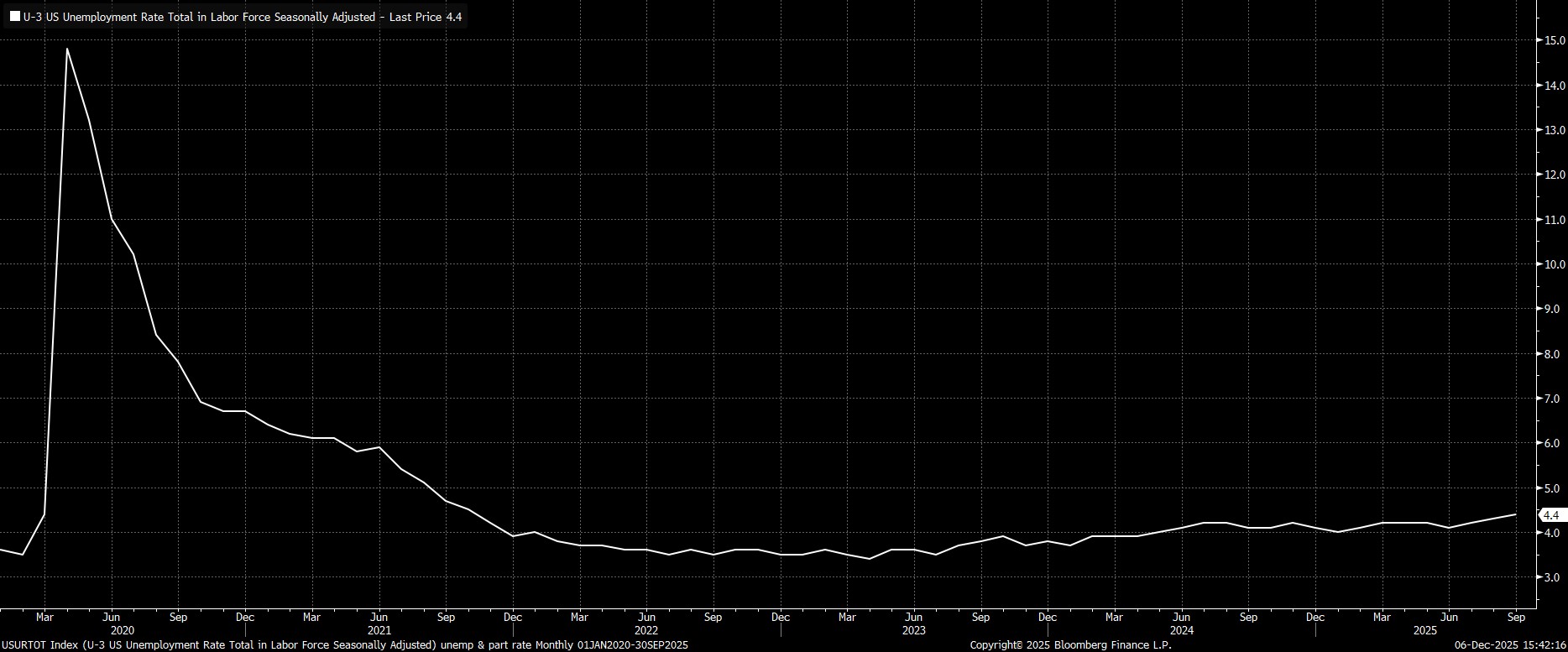

While the labour market has notably weakened through the second half of 2025, amid not only job creation slowing essentially to a crawl, but also unemployment rising to a cycle high 4.4%, there remain few signs of structural issues. Instead, this employment stasis, characterised by a ‘no hire, no fire’ jobs market, seems to stem largely from a combination of increased economic uncertainty as corporates adjust to the Trump Admin’s trade policies, coupled with potential productivity enhancements from AI resulting in a slower pace of hiring.

It’s plausible to expect that this ‘muddling through’ labour market turns into one which sees a notable pick-up in hiring activity next year, not only amid an increasingly certain policy backdrop, but also amid a looser monetary policy environment, and as businesses across the US reap the rewards of tax benefits and investment incentives. That said, while hiring is likely to pick-up, resulting in a gradual decline in the unemployment rate through the course of the year ahead, the breakeven pace of payrolls growth is likely to remain in the 30k – 70k region, primarily owing to the aforementioned labour supply constraints.

In any case, with the FOMC’s reaction function tilted clearly towards the labour market, and likely to remain so, downside risks to the employment market seem relatively limited, given that any further signs of stalling are likely to be met with a rapid, and forceful, policy response. In fact, it will likely prove to be a re-acceleration in the labour market, and subsequent rebound in economic growth, that give the Committee comfort to bring the easing cycle to a conclusion by the second half of the year.

Risks Facing A Return To ‘Normal’

While, on the whole, 2026 is likely to mark a return for the US to a more stable policy backdrop, and ultimately something that could reasonably be described as a more ‘normal’ economic environment, risks do remain.

Perhaps the most significant, if obvious, of these risks would materialise were the ongoing AI capex boom to stall, or come to an end, either as a result of increased investor scepticism as to RoI timelines, or potentially as corporates pull back on this front, as productivity gains fail to be realised. In any case, given the degree to which AI-related stocks are ‘priced to perfection’, and the increasingly circular nature of financing within the sector, any signs of cracks here could quickly spiral into a broader market rout, and subsequent negative wealth effect, which may exacerbate any broader downside macroeconomic effects.

Elsewhere, there remain concerns over the private credit space, especially given the somewhat opaque nature of valuations in the sector, though loans to the sector only represent around 5% of total bank assets and with high capital buffers, and high bank profitability, any problems in the space should prove manageable for the time being. Meanwhile, there remains a risk that a significant deterioration in labour conditions, while not the base case, could see the Fed caught significantly ‘behind the curve’, as well as the potential for President Trump to become something of a ‘lame duck’ into 2027, were the Democrats to win back control of the House and/or Senate, thus complicating the legislative agenda.

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.