- English (UK)

2026 UK Macro Outlook: Risks Aplenty As ‘Doom Loom’ Continues

Summary

- Fiscal Fragility: Despite boosting 'headroom' in the Budget, fiscal fears persist, with the bulk of tax hikes back-loaded

- BoE Easing: A couple more Bank Rate cuts remain on the cards, though debate on the MPC will intensify as the neutral rate nears

- Anaemic Growth: The continued emergence of labour market slack, plus slower consumption, will likely keep growth sluggish

2025 proved to be another sub-par year for UK Plc, amid constant fiscal fears, anaemic economic growth, a weakening labour market, and stubbornly high inflation. While there are increasing signs that price pressures have likely now peaked, many of the issues that plagued the economy this year are set to persist into next, with further labour market slack set to emerge, and political backdrop remaining a perilous one.

Fiscal Fears To Persist

While the 26th November Budget has now been and gone, the policy measures announced by Chancellor Reeves are likely to do little to either materially improve the UK economic outlook, nor to materially reduce the risk of the ‘doom loop’ continuing for another year, despite headroom against the fiscal rules having been more than doubled, to £22bln.

Although such a degree of headroom, at least compared to recent Budgets, looks healthy, the composition of the fiscal consolidation that the Chancellor is proposing to deliver takes a significant degree of shine off those headline metrics. Put simply, the Budget was very much delivered with one audience in mind – the Parliamentary Labour Party – with the aim of ensuring the political survival of both Reeves, and PM Starmer, as opposed to improving the growth outlook, not least with the OBR noting that the Budget contains a total of zero measures that significantly boost GDP growth expectations.

Consequently, the Budget was a ‘classic’ Labour one which can be summed up by the mantra of ‘tax and spend’. However, while the approx. £10bln of spending increases, largely on welfare, that were announced are front-loaded, the tax hikes that are supposed to pay for this greater spending, and shore up the fiscal foundations, are back-loaded, not only to the end of the forecast horizon, but also to the year of the next general election.

This is where consolidation plans start to fall down, and lose credibility, as it seems highly unlikely any government would seek to raise the tax burden to its highest level on record, and then head straight to the ballot box. Consequently, it is dubious as to whether many tax proposals (e.g. mansion tax, EV pay-per-mile, etc.) will actually come to fruition. This, combined with the still narrow margins with which the Treasury are operating, means that there remains a relatively high probability that a significant fiscal tightening will again be required in the 2026 Budget, for the third year running.

Political Risks Aplenty

With that in mind, it is perhaps unsurprising that political risks remain significant, and are in fact likely to grow throughout the next year.

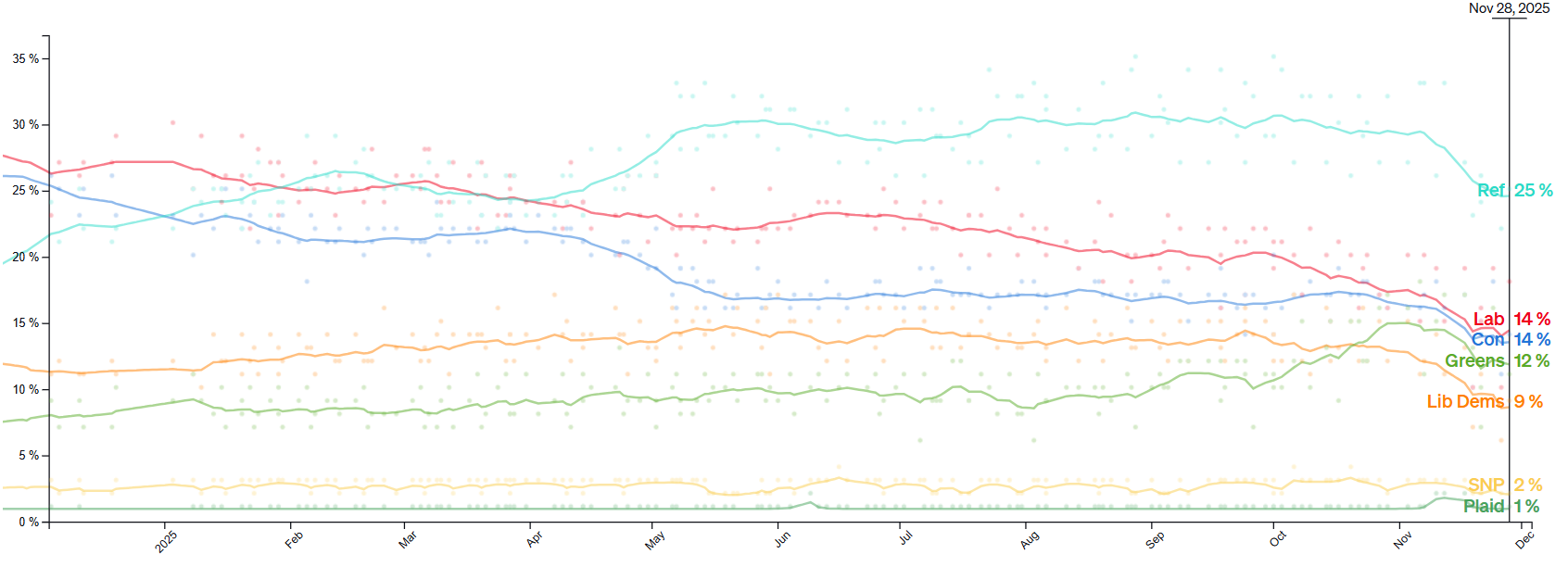

Although the Budget has likely bought the government some time, and pacified restless Labour MPs for the time being amid the scrapping of the 2-child benefit cap, this relative calm seems unlikely to be maintained for particularly long. Next spring still seems like the most dangerous moment for the current administration to navigate, with local elections due to be held across England, as well as national polls in both Scotland and Wales. Current polling points to Labour faring terribly in all of these polls.

Consequently, it seems plausible to expect those elections to act as the ‘straw that breaks the camel’s back’ among the PLP, with a post-election leadership challenge increasingly likely. If such a challenge were to occur, PM Starmer would by default be able to stand in a subsequent contest, though his chances of success would likely be very low indeed. Instead, his successor is likely to be a candidate who stands politically to the left of the current government, representing the broader position of the Labour Party membership base.

It can, hence, be reasonably expected that any replacement for the current PM-Chancellor duo would likely demonstrate significantly less in the way of fiscal discipline, and possibly also adopt a looser version of the current fiscal framework. Such a leadership contest would undoubtedly trigger higher volatility in UK assets, with a result in line with the aforementioned base case likely tilting risks to those assets to the downside.

The ‘Old Lady’ To Keep Cutting

Despite these political risks, the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee are set to continue to remove policy restriction.

A 25bp cut at the final meeting of 2025 seems near-certain at this stage, with another such cut at the following meeting in February 2026 also likely, as the MPC take comfort from a number of signs that inflation has now peaked, while also seeking to prevent a significant degree of labour market slack from emerging.

The key debate for 2026, therefore, will begin to centre around where the terminal rate likely lies, as well as whether policymakers see it as appropriate to lower Bank Rate below estimates of its neutral level. BoE models largely point to neutral as sitting around 3.50%, though the GBP OIS curve currently prices Bank Rate bottoming out around 3.25% towards the tail end of next year. Clearly, with risks to growth tilted clearly to the downside, risks to this policy path tilt rather firmly towards a potentially more dovish outturn as well.

Inflation Peaked, But Journey To Target Will Be Slow

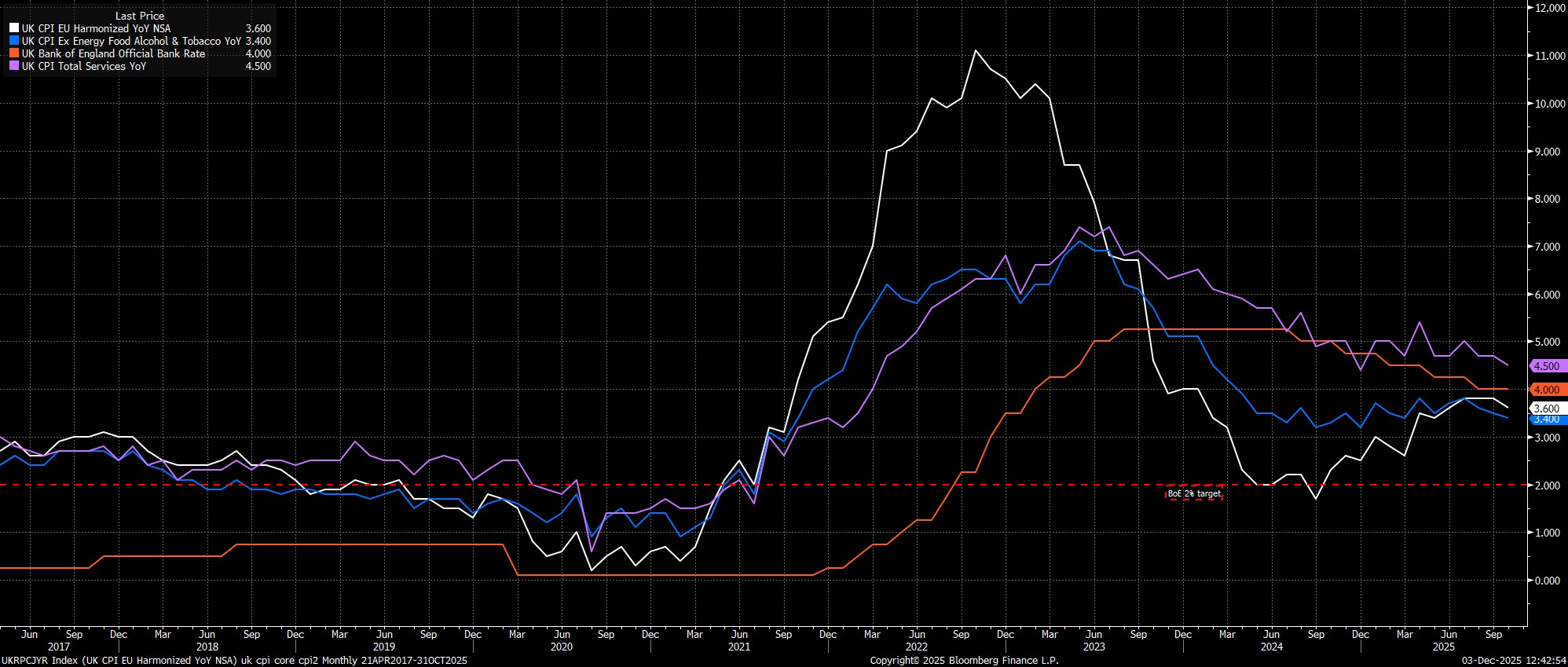

Permitting a more dovish BoE policy path, including the 25bp cut that will be delivered at the December meeting, is a strong belief among policymakers that price pressures have now indeed peaked.

Headline CPI rose 3.8% YoY in September, before slowing to 3.6% YoY in October, in line with the Bank’s forecasts, with a notable cooling also evident in underlying core and services price metrics. Added to which, while the Budget contained little by way of measures to boost economic growth, it also contained very few inflationary policies, in fact being more likely to exert a modest degree of disinflationary pressure, particularly in terms of energy and transport prices. In light of that, one can be reasonably confident that the worst of the inflationary wave is now behind the UK economy.

However, while it is undoubtedly a positive that price pressures have now likely peaked, it is too early to ‘pop the champagne’, with the journey back to the 2% inflation target likely to be a relatively slow one. Said journey shan’t be helped by the significant minimum wage increase due to come into effect at the start of the new fiscal year, the costs of which will, at least in part, likely be passed on in the form of higher consumer prices. Consequently, headline CPI is likely to remain north of 3% for at least the first half of next year, and is unlikely to return to the 2% target until 2027.

Further Labour Market Slack On The Cards

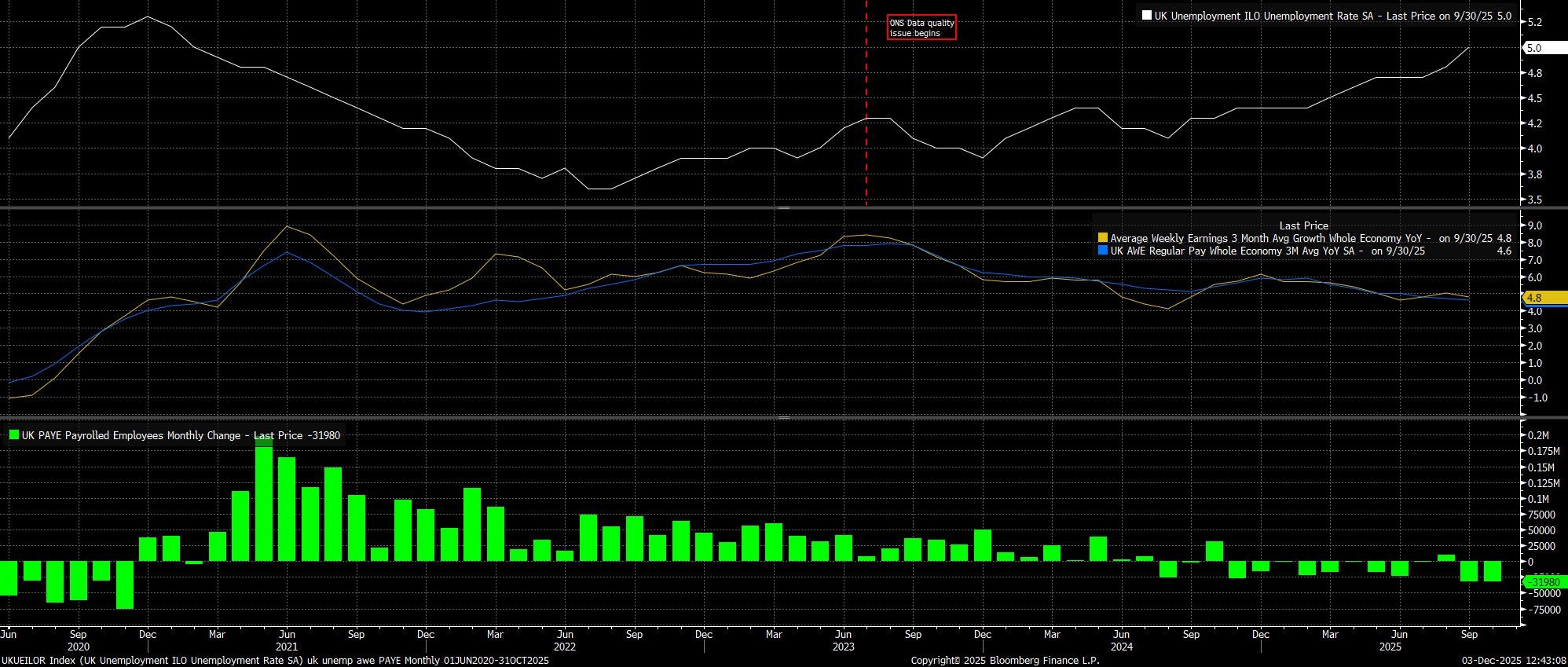

The labour market has weakened significantly in 2025, not only with unemployment having risen to 4-year highs at 5.0%, but also with payrolled employment having declined in eleven of the last twelve months, largely as a result of employers trimming headcount in reaction to last year’s substantial rise in employer National Insurance contributions.

Although the labour market has now, by and large, adjusted to these higher employment costs, risks to the outlook remain tilted to the downside, not only as a result of still-elevated cost pressures, but also as economic growth at large remains anaemic.

Perhaps the most important labour market development next year, though, will be the evolution of earnings growth, which has continued to run at a pace incompatible with a sustainable return to the 2% inflation target, albeit with said pay growth largely propped up by the public sector, in turn somewhat masking a degree of underlying fragility in the labour market at large.

Anaemic Growth To Persist

Against the backdrop of a continued weakening in labour market conditions, plus with the BoE maintaining a relatively restrictive policy stance, and with upcoming tax hikes denting personal consumption, another year of relatively anaemic economic growth seems likely to be on the cards.

The case for such a sub-par pace of expansion is supported by, as mentioned earlier, the fact that the Budget brought with it no policy measures to boost either growth or investment, while the labour market poses a notable risk, not least amid what seems a relatively complacent consensus view that recession will be avoided, despite unemployment already running close to levels which have been consistent with such an eventuality in the past.

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.