- English

- عربي

The FOMC Seem Too Sanguine About The Ailing US Labour Market

Summary

- FOMC On Hold: The FOMC seem to have sought solace in a stabilising unemployment rate, hence having shifted towards a 'wait and see' policy stance

- Fragile Under The Surface: However, under the surface, downside labour market risks appear mor significant, and point to a greater margin of slack being present

- Dovish Risks: In turn, this presents potential dovish risks to the policy outlook, particularly if this fragility results in a non-linear rise in unemployment

The FOMC sprung no surprises at last week’s policy meeting, standing pat on rates as expected, with policymakers having seemingly been reassured by recent labour market data that a ‘wait and see’ approach is now appropriate.

I’m starting to wonder, though, whether the Committee might well be a little over-confident in the state of the employment backdrop.

Unemployment Stabilising For The ‘Wrong’ Reasons

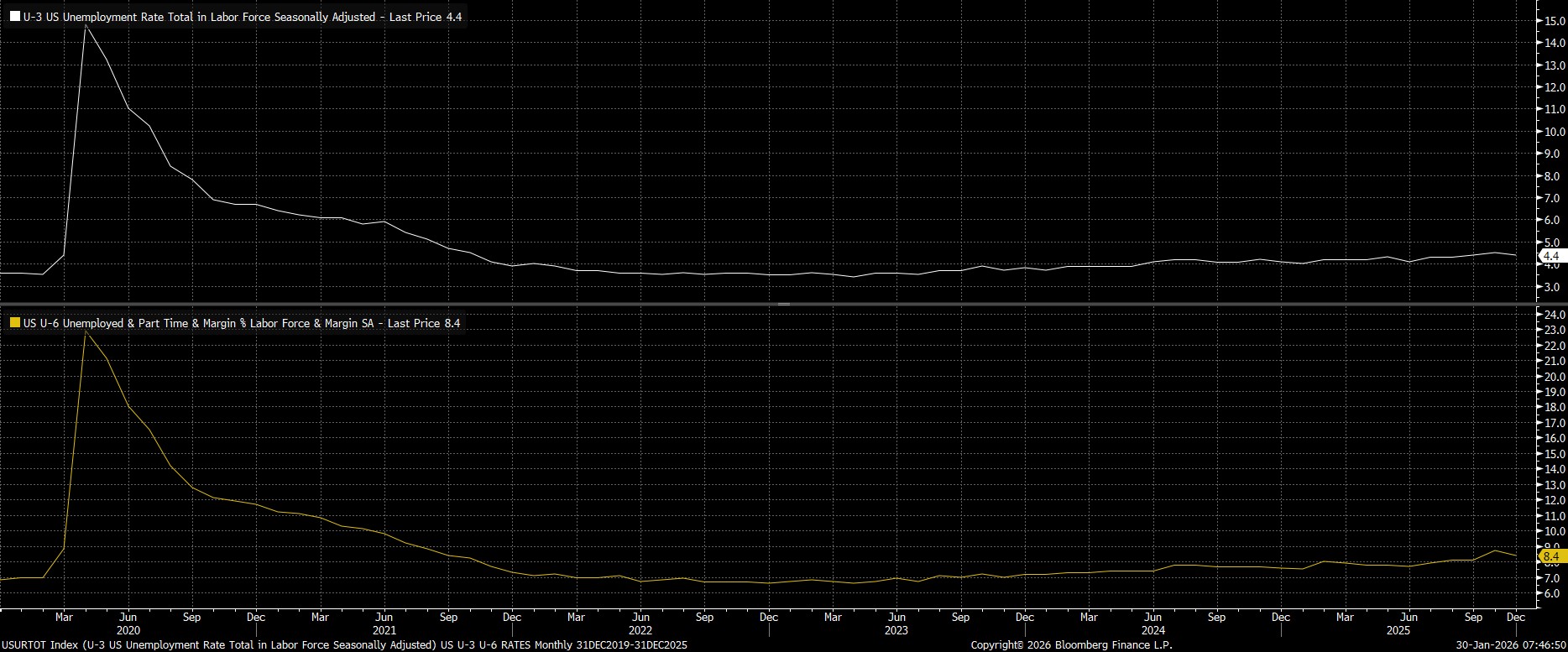

The little-changed policy statement noted that the unemployment rate has ‘shown some signs of stabilization’, while Chair Powell struck a similar tone at the post-meeting presser, noting that the labour market may be ‘stabilising’ after a period of what he described as ‘gradual softening’. At a headline level, at least, these statements are indeed correct, with both unemployment (U-3) and underemployment (U-6) having declined notably in December.

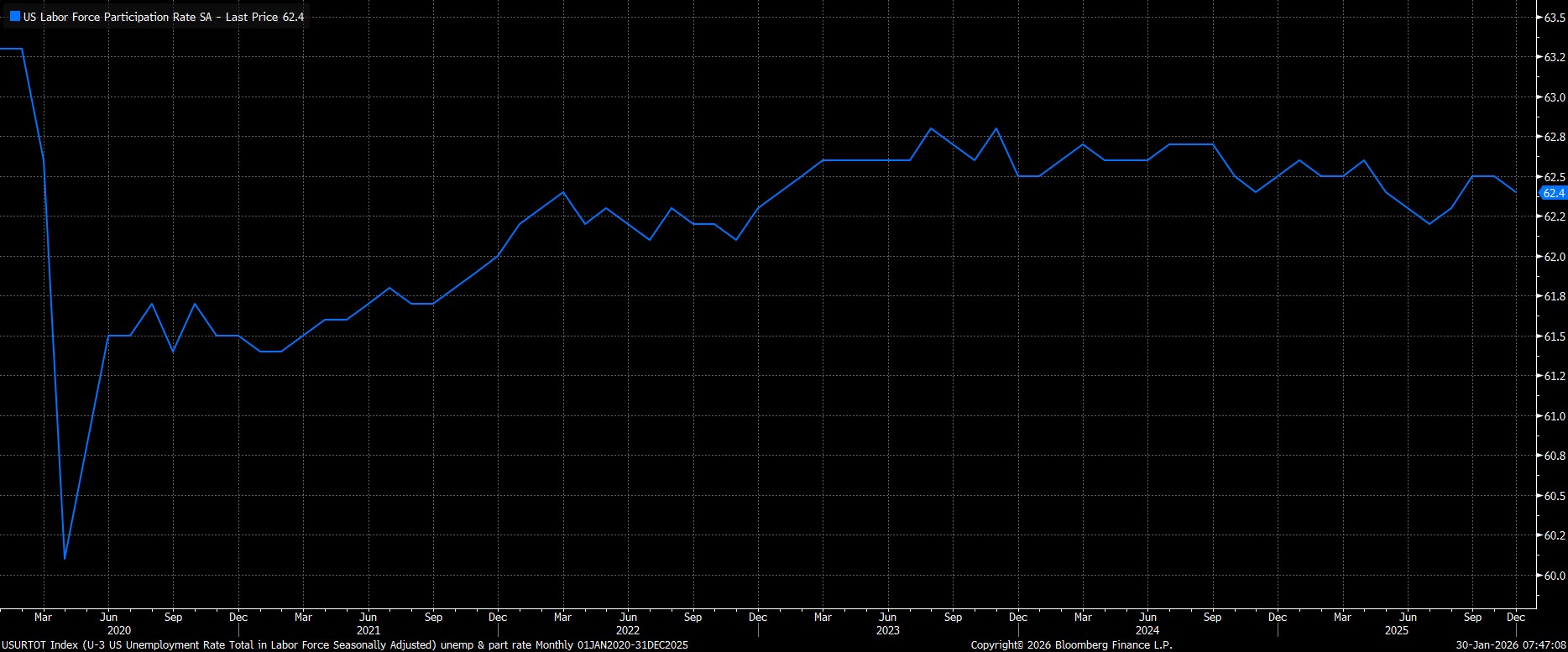

That decline, though, was not driven by people finding work, but was instead driven largely by people leaving the labour force altogether. Participation fell to 62.4% last month, in a sign that workers are likely becoming discouraged from finding employment as a result of the ‘no hire, no fire’ labour market dynamic which currently dominates, and hence are abandoning their search for work.

Noncyclical Private Hiring Is Non-Existent

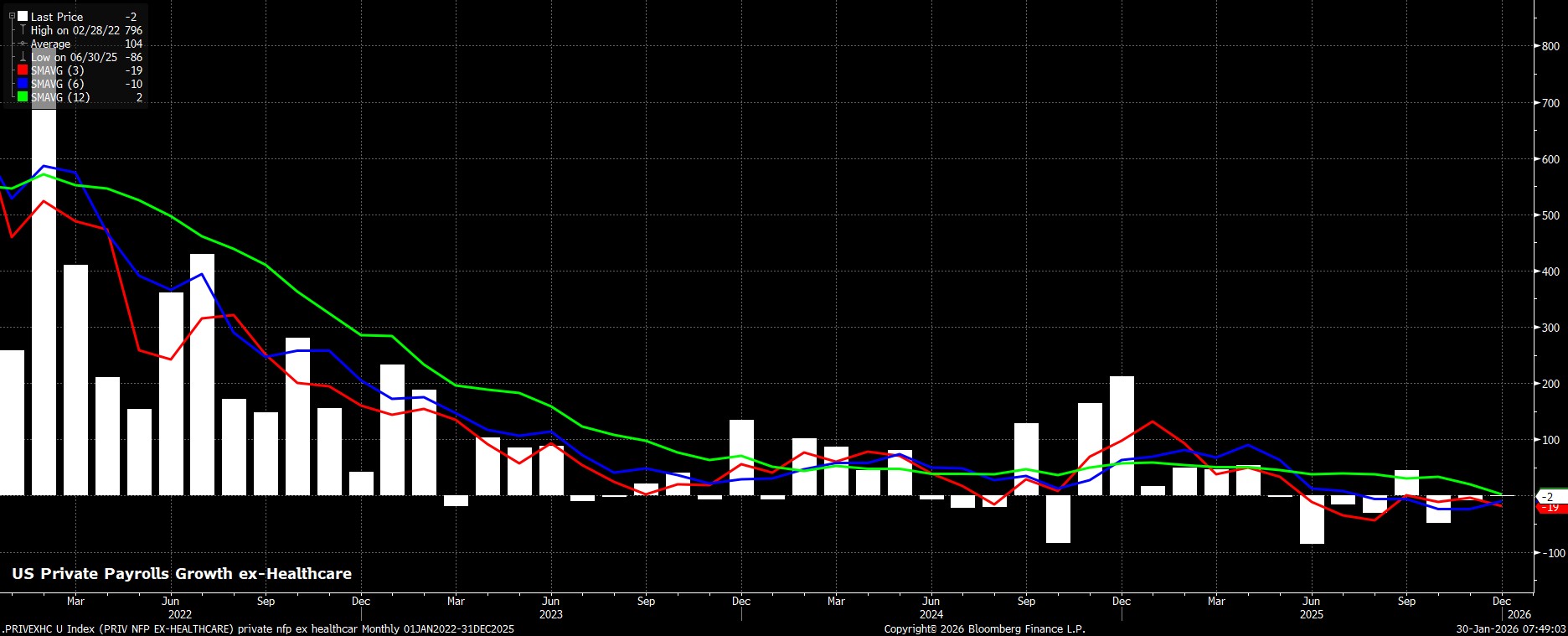

That dynamic is well-evidenced by the establishment survey. Private payrolls excluding healthcare remains my preferred metric on this front – I exclude the healthcare sector as it is noncyclical, domestically-focused, and very much non-rate sensitive. Doing so paints a starkly different picture of the employment backdrop. The 3- and 6-month averages of this metric of job creation both sit comfortably in negative territory, while private employment ex-healthcare has actually fallen in every month bar one since last May.

Put another way, without the addition of healthcare jobs, the private sector would’ve added just 20k new roles over the entirety of 2025!

Layoffs Are Starting To Accelerate

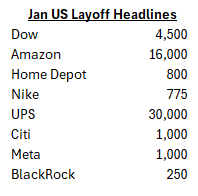

To my mind, that’s speaks volumes about the lacklustre pace of hiring in the economy at large. Added to which, signs are now emerging that the ‘no hire, no fire’ backdrop could well be shifting, with the balance increasingly tilting towards layoffs.

A cursory glance over recent corporate reports indicates job losses likely to pick-up across sectors, with some of the most notable recent announcements including UPS’ plans to shed 30,000 staff, Amazon laying off as many as 16,000 employees, Dow planning to trim headcount by over 4,000, with smaller layoffs also having been announced by numerous financial services and technology firms. The risk, here, is that the pace of these layoffs ramps up further, resulting in a rapid and non-linear increase in unemployment.

Jobless Claims Sending A False Signal

Some would point to the relatively subdued level of both initial and continuing jobless claims as evidence that the labour market is not in as fragile a way as I’m implying here. However, again, the message here is likely not as rosy as the relatively benign headline metrics – with initial claims having averaged 206k over the last four weeks, and continuing claims at around 1.850mln – might imply.

Typically, US unemployment benefits are paid for a maximum of around six months, with some variation from state-to-state. Hence, the somewhat benign level of jobless claims likely owes not to claimants finding work, but instead because they are no longer eligible to claim unemployment insurance, having been out of work for longer than the maximum duration for which said payments can be made.

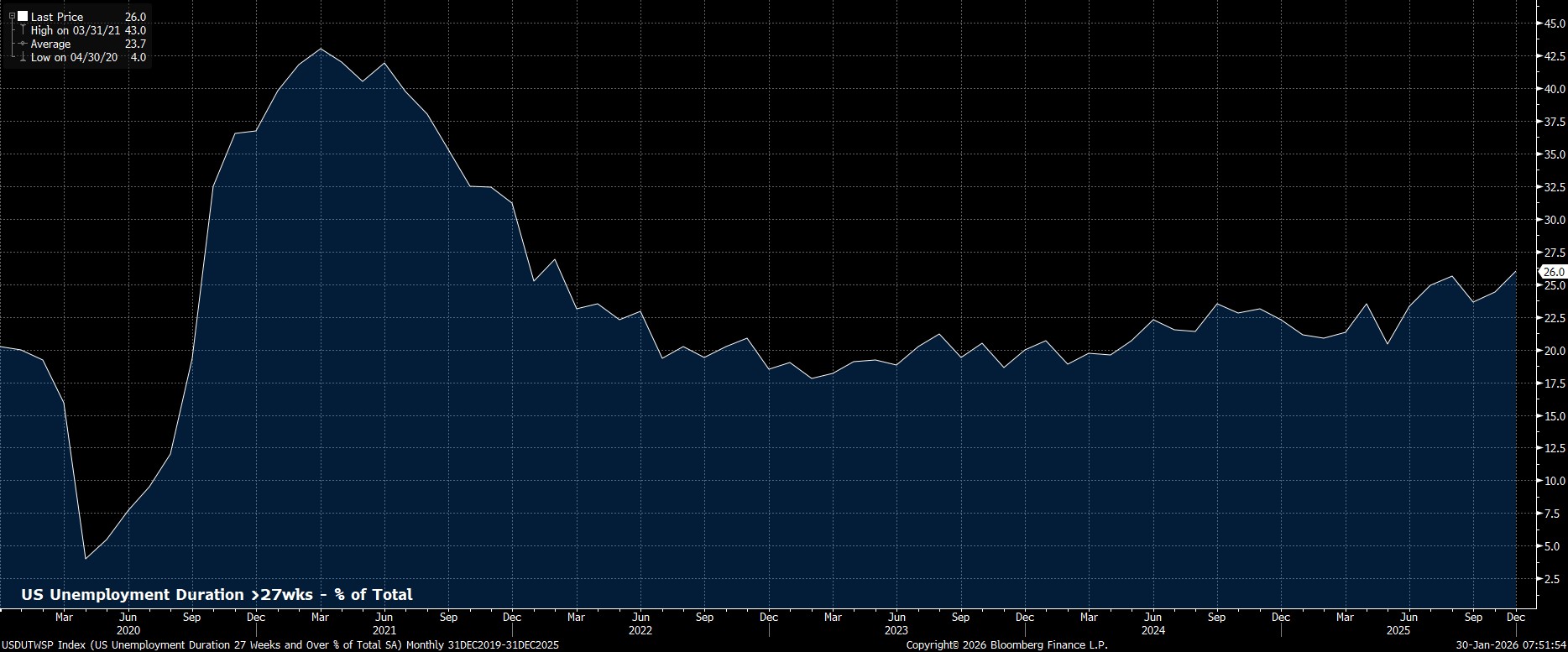

Once again, the BLS employment report supports this thesis. We’ve already shown that private sector hiring is at best anaemic, and at worse non-existent. The data also shows that 26% of those classified as unemployed have now been so classified for more than 27 weeks (i.e. > 6 months), with that not only being the highest such level since early-2022, but also having risen dramatically from around 20.4% just eight months ago.

Consumer Confidence Reflects Reality ‘On The Ground’

In turn, this helps to explain the dire consumer confidence metrics that we received this week. Not only did the Conference Board’s headline index fall to its lowest level since 2014, but the ‘jobs hard to get metric’ rose to its highest level since the pandemic, largely reflecting the underlying labour market weakness outlined here, and going some way to dispel the false confidence that headline labour metrics may provide.

Now, as I’ve written before, in a ‘K-shaped’ economy such as the US at present, such a nosedive in consumer confidence need not trigger a sharp slowdown in consumer spending. The marginal propensity to spend continues to hinge much more on the ‘wealth effect’, with higher income deciles continuing to make up the vast majority of overall consumption.

That said, if the bottom of that ‘K’ is to catch-up with the economy at large, it is irrefutable that labour conditions will have to improve in order to enable that to happen. Right now, however, those very labour conditions are moving in the polar opposite direction.

FOMC At Risk Of Falling Behind The Curve

Pulling things together, we have a situation where headline employment metrics are likely providing a degree of false reassurance to policymakers as to the state of the labour market. Under the surface, things appear considerably more fragile, with there remaining a significant risk that the situation tips from one of ‘slow hiring, and slow firing’, to one where the pace of layoffs dramatically picks-up, and conditions sour more broadly.

The FOMC appear somewhat too sanguine about these risks, at least given Wednesday’s statement and presser, presenting a notable risk that policymakers may fall behind the curve. Against such a backdrop, the USD OIS curve discounting just 8bp of easing by April, and only two 25bp cuts this year (both in H2), feels too hawkishly priced.

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.