- English

- عربي

Rachel Reeves has got a problem on her hands.

In fact, the Chancellor has actually got many issues to deal with right now, as the economy remains trapped in a fiscal doom loop, and the ‘black hole’ needing to be plugged at the autumn budget appears to deepen by the day.

Her biggest issue, though, is one that hasn’t attracted anywhere near as much attention as it deserves, probably because it sounds rather boring and technical in nature – namely, the changing composition of participants in the Gilt market.

To dig into this, we need a bit of historical context. A decade or two ago, the market for Gilts was dominated by price-insensitive buyers, principally in the form of pension funds, and life insurers, who were purchasing Gilts at the long-end of the curve, as a relatively simple way to hedge off their known, and long-standing liabilities.

Since then, though, there has been a significant change in the UK pensions industry. Gone, by and large, are the days of final salary (or defined benefit) pension schemes, whereby administrators would pledge a particular benefit amount, and then run a scheme simply to target that eventual payout, leaving fixed income products as an obvious solution. In their place have come defined contribution schemes where, not only is the final benefit dependent on amounts paid in through an employee’s working life, the range of investment options is typically much wider, with said employee often choosing to invest a larger proportion of their savings in the equity complex.

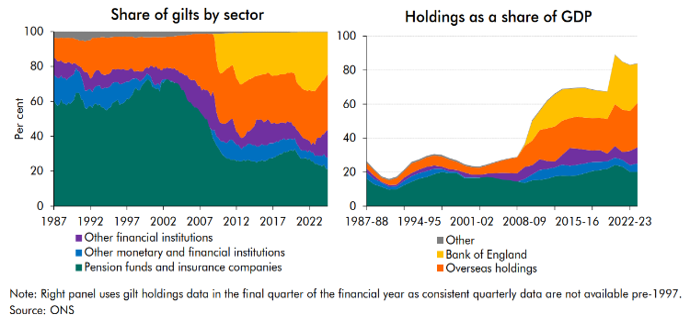

As DB pension schemes wind down, and DC schemes become increasingly prevalent, it logically follows that pension and insurance firms will have much, much less of a need to engage in the Gilt market. In fact, data from the OBR bears this out, where ownership of Gilts among that contingent has fallen from over 70% 25 years ago, to a little over 20% now.

In their place have come price sensitive buyers, namely hedge funds and other overseas investors. In sharp contrast to pension funds, who simply seek to hold Gilts in order to hedge their DB portfolio risks, participants with considerably more mobile capital, and considerably more investment options, have entered the fray. Consequently, said participants could be considered as much greater ‘flight risks’ than those they have replaced.

How does this all pose a problem for Reeves? Put simply, the Chancellor finds herself in the eye of a ‘perfect storm’, needing to ramp up Gilt issuance to fund an ever-increasing public spending bill, just as the natural pool of buyers for Gilts dries up. While there will always be a buyer out there, enticing those buyers to enter the market is likely to require a much greater degree of compensation (i.e., a higher yield) than in years gone by.

Quite obviously, higher Gilt yields will further increase the UK’s debt servicing bill, thus further deepening the ‘black hole’ that we keep hearing so much about. It might also be possible to entice those participants to enter the fray by shortening the DMO shortening the WAM of issuance each year, and ramping up front-end sales, though this would be rather short-sighted, and again leave the economy vulnerable to a rate shock in the future.

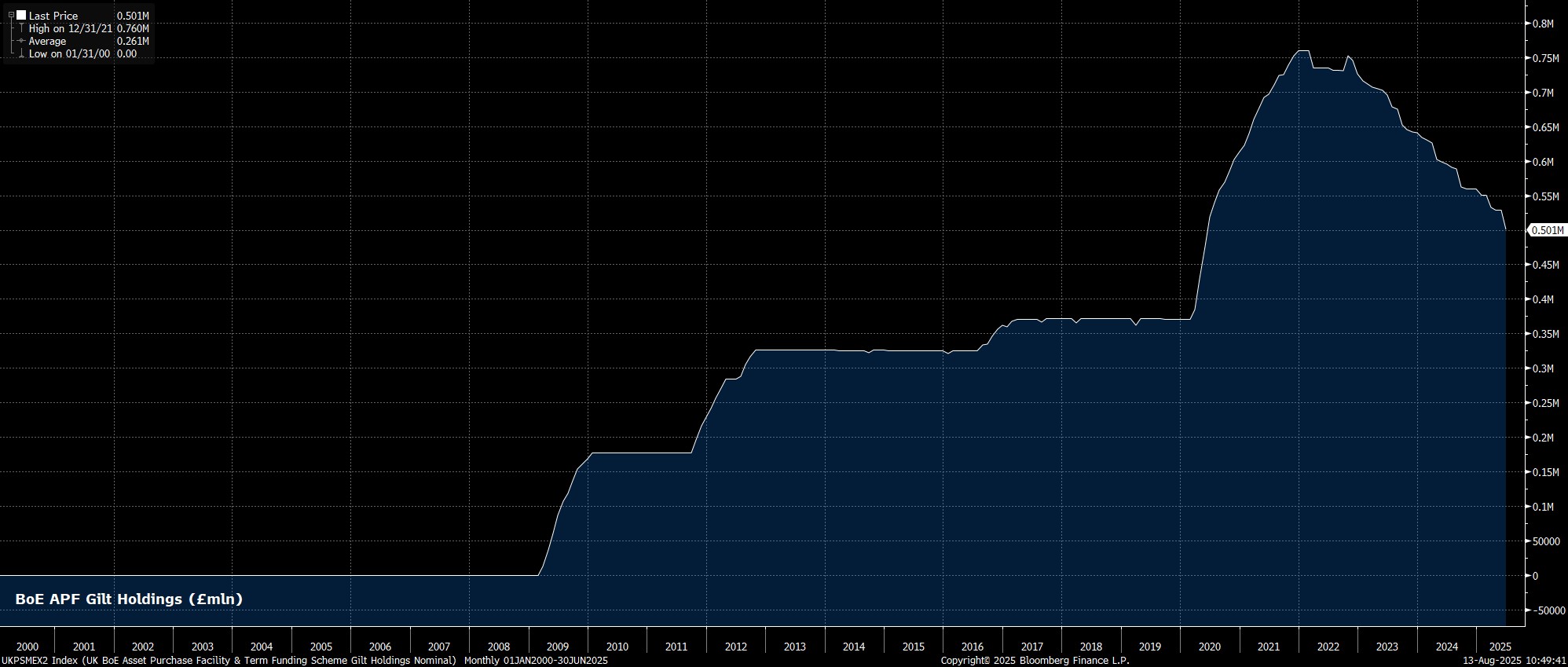

That’s not the end of the story though. Pension funds are not the only price inelastic buyers to have exited the fray, with the Bank of England having also pulled back sharply in recent years, and having also done so in relatively aggressive fashion.

The ‘Old Lady’ began to purchase Gilts in early-2009, kicking off the process of quantitative easing in response to the GFC, while then further increasing Gilt holdings in the aftermath of the Brexit vote, and during the pandemic. Since the start of 2022, however, the Bank have been unwinding those Gilt purchases, not only allowing maturing securities to roll off the balance sheet, but also conducting outright sales of certain securities, across the curve.

Reeves, then, has two issues to deal with here – one set of price insensitive buyers being replaced with price elastic ones, while another previously price insensitive buyer aggressively sells down their holdings.

When you pile these on top of the fact that further tax hikes to ‘balance the books’ are akin to pushing on a string, and consider the near-impossibility of the Commons passing spending cuts to anything like the magnitude that would make a dent in improving the public finances, it becomes very difficult, if not impossible, to argue that the balance of risks tilts in any direction other than downwards, especially at the long-end of the curve.

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.