- English

- عربي

To unpack this, we first need to go back to the aftermath of the financial crisis, when the SLR was first introduced. In layman’s terms, the SLR mandates that large US banks maintain a total of 5% of their capital against all bank assets, making no allowances whatsoever for the perceived riskiness of those assets. Hence, 5% capital must be held whether those assets are Treasuries, or whether they are much riskier forms of paper such as MBSs.

This has, perhaps obviously, long been a source of consternation for the largest US banks, given the need to apparently unnecessarily tie up capital to be held against what unarguably remain the safest government bonds in the world. Put simply, US banks have little-to-no incentive to be holding the debt that their own country is issuing.

There is also a competitiveness issue here as well, given that the SLR at 5%, its level at the time of writing, is considerably more than the 3% leverage ratio that was stipulated in the Basel III framework. Hence, in this respect, US banks are forced to hold a much greater degree of capital than their international peers, posing a modest headwind in terms of relative performance.

Against this backdrop, the increasing clamour to change the SLR – either to scrap it entirely, or to lower it considerably – makes a lot of sense.

However, it is not only the banks that this change is likely to benefit. Tweaking the SLR should, in theory, provide an incentive to banks to increase their purchases of Treasuries, potentially in a significant manner. This, at a time when jitters over the US’s fiscal backdrop continue to mount, and at a time when international investors are taking an increasingly sceptical view of Stateside assets, could prove very helpful indeed for the Trump Administration.

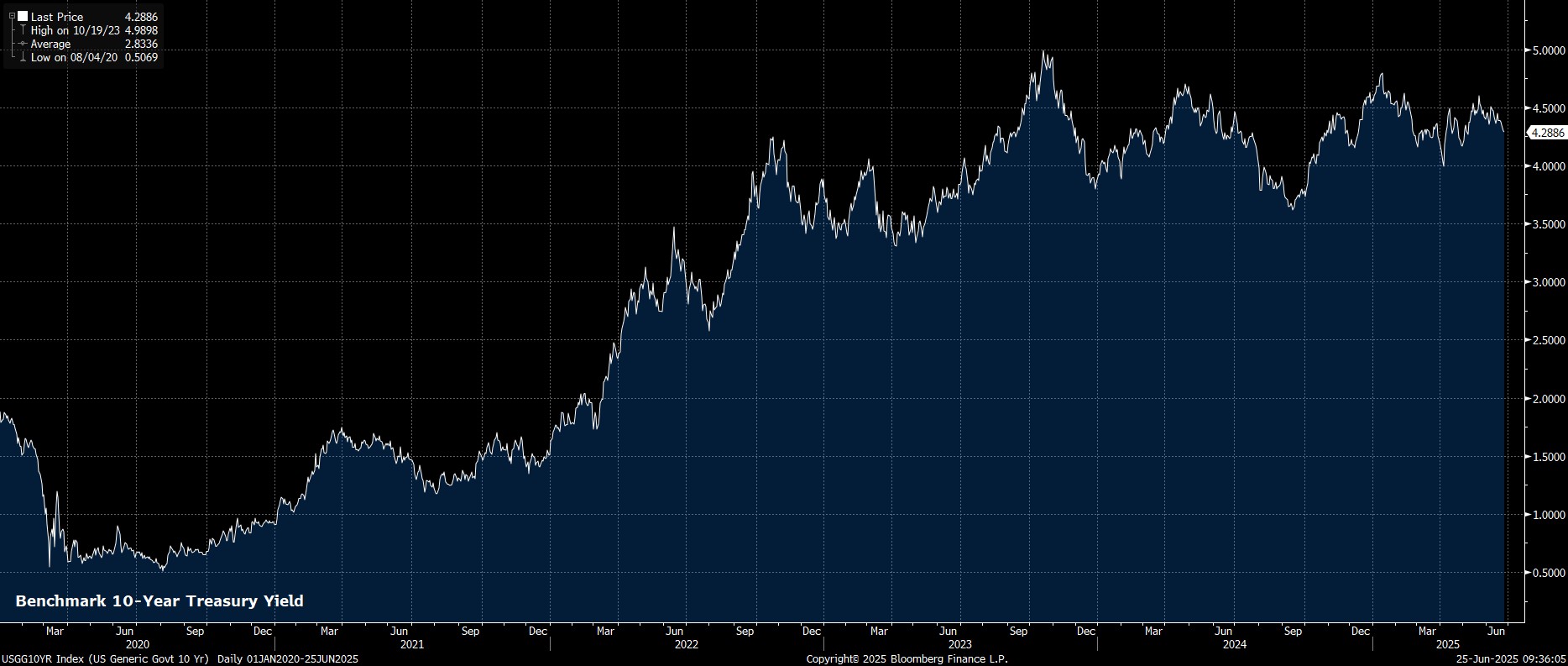

Things are, as always, not quite as simple as that however, in the event that the SLR were to be changed. Just because banks can increase their Treasury holdings, it doesn’t necessarily mean that they will want to. In order for banks to be convinced that they should be increasing their holdings, they don’t just need SLR reform, but also to be sure (or at least have a solid expectation), that long-end rates will decline over the medium-term.

Of course, if long-end rates were to rise, even though the Treasuries in question would likely be held to maturity, large mark-to-market losses can be created which, if holdings subsequently need to be sold down, the bank in question will have to absorb a chunky loss.

Taking that into account, it seems highly implausible that simply relaxing the SLR will suddenly see banks flocking to buy Treasuries en masse. Although Treasury Secretary Bessent has touted the potential for a 70bp fall in long rates if the SLR was abolished entirely, such a sizeable mov appears relatively unlikely, unless the aforementioned confidence around a more sustainable fiscal path is obtained.

Perhaps a better way to frame the impact of potential SLR changes is via its ability as a ‘shock absorber’.

Often, in times of economic strife, where banks tend to feel more pressure on capital requirements, they can begin to step away from certain market activities, as was seen at the beginning of the pandemic, when institutions increasingly pulled back from the Treasury market. Back then, temporary SLR changes in April 2020 sparked a dramatic improvement in liquidity conditions, when both cash deposits and Treasuries were excluded from the calculation.

As a result, it may well prove to be in times of crisis that the impacts of any SLR become most obvious. Were the Treasury market to be at risk of seizing up at some stage in the future, a lower SLR would likely make it considerably less likely for banks to pull back from the complex, potentially lessening the risk of significant issues here, while also potentially raising the bar for the Fed to intervene, if markets were able to ‘self-serve’ in a more efficient manner.

More broadly, murmurings of SLR reform is yet another factor that again speaks to the Trump Administration attempting to take the ‘easy’ way out of higher borrowing costs.

As opposed to grasping the nettle and taking the tough choices to bring down the deficit, and place the US economy on a more sustainable fiscal path. The Admin continue to fiddle around the edges – not only with talk of SLR changes to bring down market-based rates, but also with the constant badgering of Fed Chair Powell to deliver sizeable rate cuts – while having essentially given up on DOGE, and being on the verge of passing the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill’, which is set to add almost $3tln to the budget deficit.

On that issue, there are no ‘easy’ solutions. Tough decisions will have to be made, both in terms of spending cuts, and probably in terms of revenue raising too. While these issues are in no way unique to the US, SLR reform shan’t be a ‘silver bullet’ to spark Treasury demand, nor to suddenly put the US back on a more sustainable fiscal footing. Until that happens, jitters across the Treasury curve are likely to persist.

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.