- English

- عربي

Neutral Rate Revisited: Markets May Be Pricing the Fed Wrong

Summary

- History As A Guide: While models can be useful, reflecting on past instances of the Fed's dual mandate being achieved likely obtains us a more accurate estimate of where neutral lies

- Two Policy Levers: The fed funds rate alone is just one part of the puzzle, with the balance sheet of pivotal importance too in driving the overall policy stance

- Lower Neutral = Bullish Risk: A lower neutral rate than policymakers, and market participants, currently pencil in, could further support the bullish backdrop for equities, and front-end Treasuries

There can be a bit of a tendency to over-complicate things in this game; and, I’ll happily admit to falling victim to that on perhaps more than my fair share of occasions.

Hence, let’s revert to ‘first principles’ for a bit, and adopt the KISS strategy – Keep It Simple Stupid.

What A Neutral Rate Really Means

Consider what the FOMC are trying to achieve. The dual mandate gives policymakers two aims, to ensure price stability, and maximum employment. Commonly, we, and the Fed, define those objectives quantitatively as 2% inflation (measured by the PCE gauge), and unemployment around the 4-4.5% mark (seen as a reasonable guesstimate for NAIRU).

As policymakers now seek to remove policy restriction, the ultimate destination is likely to be the neutral rate. This is something that is very difficult, if not impossible, to quantify, but can be defined as an interest rate level where monetary policy is neither stimulating, nor restricting, economic activity. In other words, everything is nicely in balance.

While there are oodles of models out there attempting to calculate that neutral rate, perhaps the simplest way to gauge where that rate lies is to look back at recent history, and the last time that we had a ‘nirvana-esque’ economic environment. The period that immediately springs to mind is 2017 – 2019, where headline unemployment (U-3) hovered at or below the 4% mark, while headline inflation (PCE) was as near as makes no difference at the 2% target. During that time, the fed funds rate peaked at 2.50%. Everything was, judging by these variables, ‘fine and dandy’ from a macroeconomic perspective, meaning that we can reasonably assume that 2.50% fed funds rate to be a neutral monetary policy setting.

Little Suggests Neutral Should’ve Shifted

Perhaps the most important question, then, is to ask what could’ve caused that neutral rate to change, and potentially move higher, over the last decade or so.

The argument that neutral is now considerably higher, potentially between 3% and 4%, seems to rest on the idea that this must be the case, simply because nothing in the economy ‘broke’ when the Fed hiked rates north of 5% in an attempt to bear down on the covid-era inflationary impulse. This, though, misses a key part of the puzzle, in that a >5% fed funds rate was accompanied by a balance sheet that ballooned to as much as 35% of GDP. Taking these two policy levers together means that the overall policy stance was considerably looser than just a cursory glance at the fed funds rate would imply.

Quantifying the impact of balance sheet shifts on the overall stance is a bit of an imperfect science, though a decent ‘rule of thumb’ is that a +/-$1tln change in the balance sheet has an equivalent impact of +/-50bp to the FFR. This means that, in practical terms, the fed funds rate was effectively much lower, thus policy much less restrictive, during the last hiking cycle, than otherwise would’ve been the case. In turn, the argument that the neutral rate must be higher simply because a 5% FFR didn’t feel restrictive starts to lose its potency. This is especially true considering that structural arguments for a higher neutral rate (e.g. AI driven productivity gains, demographic shifts, runaway fiscal spending, etc.) also don’t hold especially much water right now.

The ‘Here & Now’

Speaking of right now, the balance sheet is back at a neutral level, at around 21.5% of GDP – unsurprisingly, roughly where it was during those ‘nirvana’ days of the late-2010s. With the balance sheet no longer cushioning against any tightening impact from the fed funds rate there is, in my mind, little reason to believe that the nominal neutral rate is any different from those days either, namely being around the 2.5% mark.

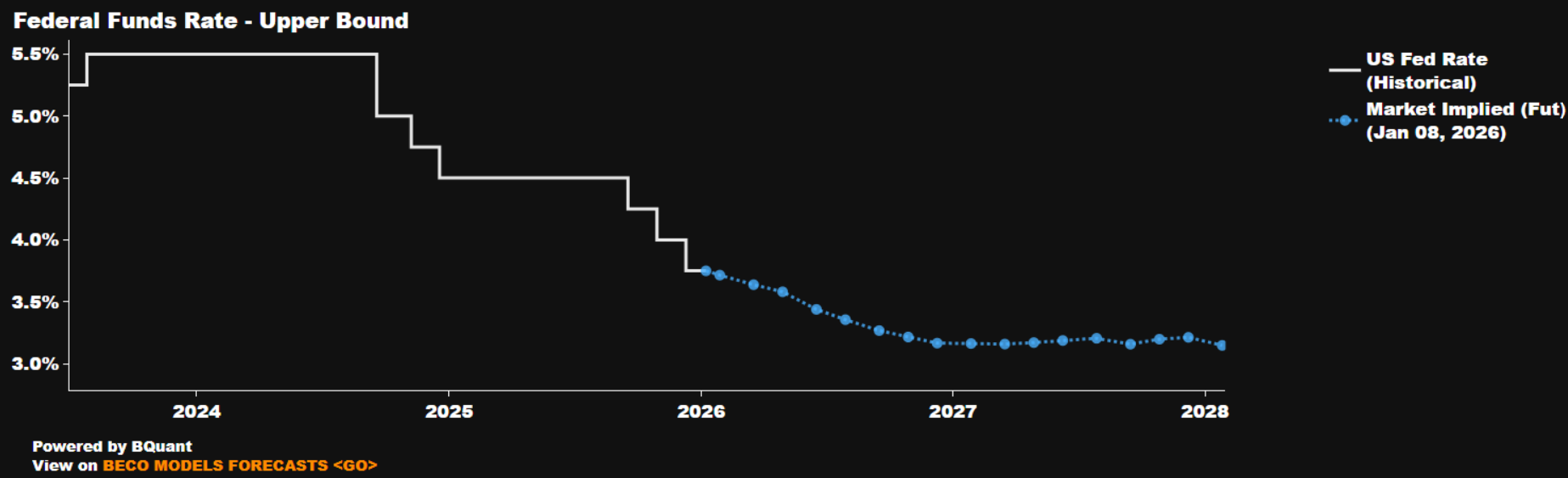

If this is indeed the case, and FOMC members have mistakenly pencilled in a much higher neutral rate than is actually the case, then the implications are relatively obvious – namely, that the ongoing easing cycle will likely last longer, and result in a much lower terminal rate, than the 3.0% by year-end that markets currently price.

In turn, such a scenario would clearly be supportive for STIRs, as well as front-end Treasuries, while also further strengthening the equity bull case, given both that the policy backdrop would be significantly looser than currently priced, implying a much stronger ‘Fed put’ structure than is currently discounted.

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.