分析

As noted, Bank Rate is likely to remain unchanged at 5.25% at the conclusion of the MPC’s June deliberations, remaining at the post-crisis high where rates have resided since last August. That said, the decision to maintain policy settings is once again unlikely to be unanimous. Instead, a 7-2 vote among MPC members is likely, with Deputy Governor Ramsden, and external member Dhingra, again set to vote in favour of an immediate 25bp cut.

Money markets price next-to-no chance of a move at the June meeting. At the time of writing, the GBP OIS curve implies just a negligible 5% chance of a 25bp cut, with the first such cut not fully priced until the November meeting. Over 2024 as a whole, markets currently discount around 37bp of easing in total, though this is subject to significant change, pending the May CPI print next Wednesday 19th June.

In any case, the MPC’s guidance, accompanying the decision to hold rates steady, is likely to remain unchanged from that issued after the May meeting. Once more, the statement should reiterate the need for policy to remain “restrictive for an extended period of time”, with policymakers also likely to again stress a focus on indications of inflation persistence as the primary determinants as to the timing of the first rate cut. In addition, the statement will reiterate the MPC’s bias towards the next move in rates being a cut, flagging that they will “keep under review” how long Bank Rate should remain at its current level.

In terms of policy restriction, minutes from the June MPC meeting – released, as always, at the same time as the statement – should repeat policymakers’ belief that a restrictive stance can be maintained, even if a modest degree of rate cuts were to be delivered.

While there remains the possibility of a dovish tilt to the MPC’s guidance, for instance explicitly flagging that cuts could be appropriate at a coming meeting, the hotter-than-expected April inflation figures have likely put paid to any immediate further dovish pivot.

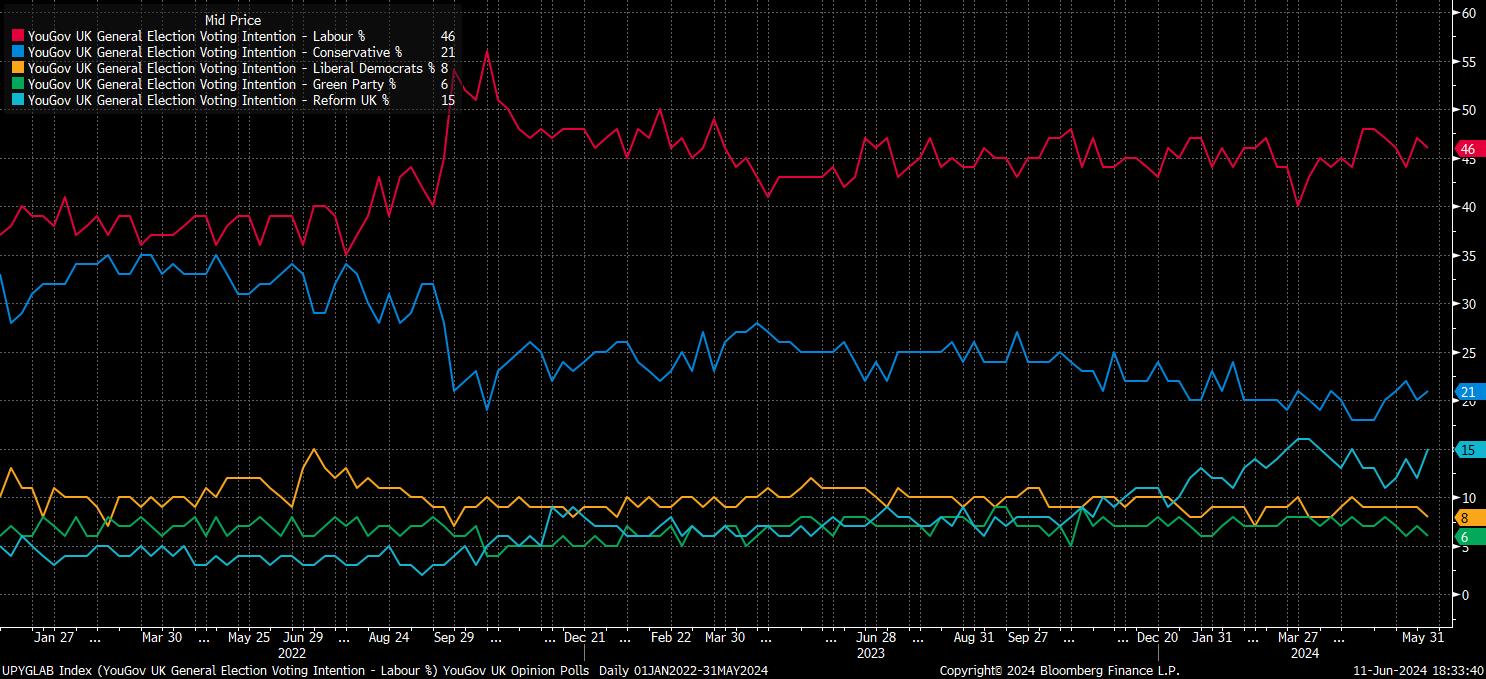

Of course, it is not only incoming data – on which, more below – that has somewhat killed the chances of a further dovish step from the ‘Old Lady’, but also the Prime Minister’s surprise announcement of a ‘snap’ general election, on 4th July.

Upon the election being called, the Bank ceased all public speaking engagements, which were already relatively rare compared to those conducted by other G10 central banks. Consequently, there has been no opportunity for MPC members to guide, subtly or otherwise, market expectations ahead of the June meeting, with the last noteworthy public remarks having been made by Deputy Governor Broadbent back on 20th May. Incidentally, the upcoming meeting will be Broadbent’s last on the MPC, having first joined the Committee as an external member in 2011, before his departure, to be replaced by OECD Chief Economist, and former senior HM Treasury official Clare Lombardelli, from the August gathering onwards. That said, given the ‘core’ of the MPC tend to vote together, and that Broadbent hasn’t dissented once this cycle, this shake-up appears unlikely to have any significant policy impact.

In any case, returning to the election, and given the uncertainty caused by the current political situation – even if opinion polling continues to point to Labour winning a sizeable majority – the path of least resistance is one where the MPC remain on hold, until the campaign concludes, and results are known.

While that provides the first reason for the ‘Old Lady’ to stand pat, incoming economic data provides two further pieces of evidence likely to deter policymakers from any immediate action.

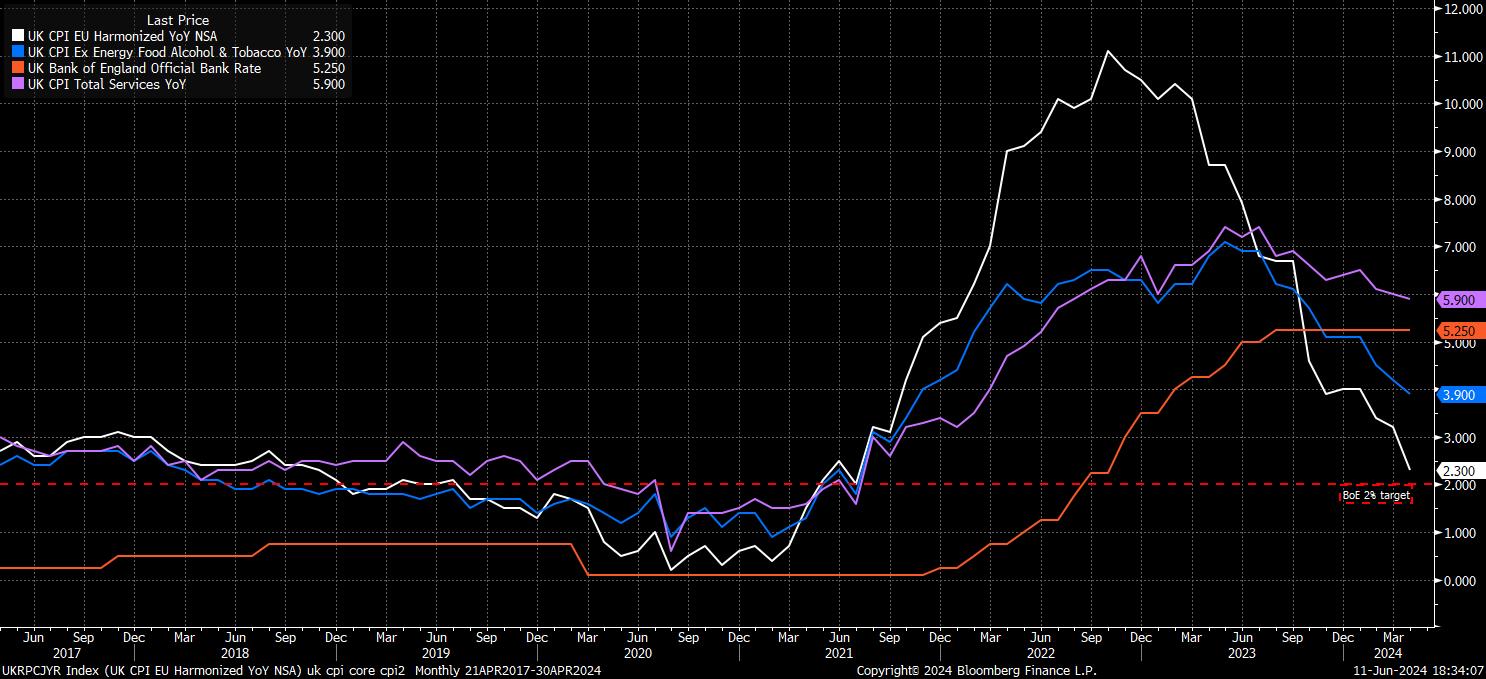

Firstly, on this front, there is the inflation backdrop. While the May inflation figures are due just a day before the policy decision’s release, and on the morning of the MPC’s scheduled vote, April’s inflation report delivered a very unwelcome surprise for those on Threadneedle Street.

Headline CPI rose 2.3% YoY in the month, above both the BoE’s own forecasts, and market expectations, albeit while still representing a chunky, and largely energy-driven, decline from the 3.2% pace seen in March. Likely of more concern to policymakers, however, given the focus on signs of inflation persistence, is the still stubbornly high rate of services inflation, with prices in said sector having risen by just shy of 6% YoY per the April data – once again, above the Bank’s forecasts.

Even if the May CPI report were to show headline inflation returning to target, and further disinflation in services prices, it seems unlikely that policymakers would take too much solace from a sole report. There is little harm, at this stage, in waiting for the August meeting, by which time another round of inflation figures would’ve been released, before pulling the trigger on the first cut.

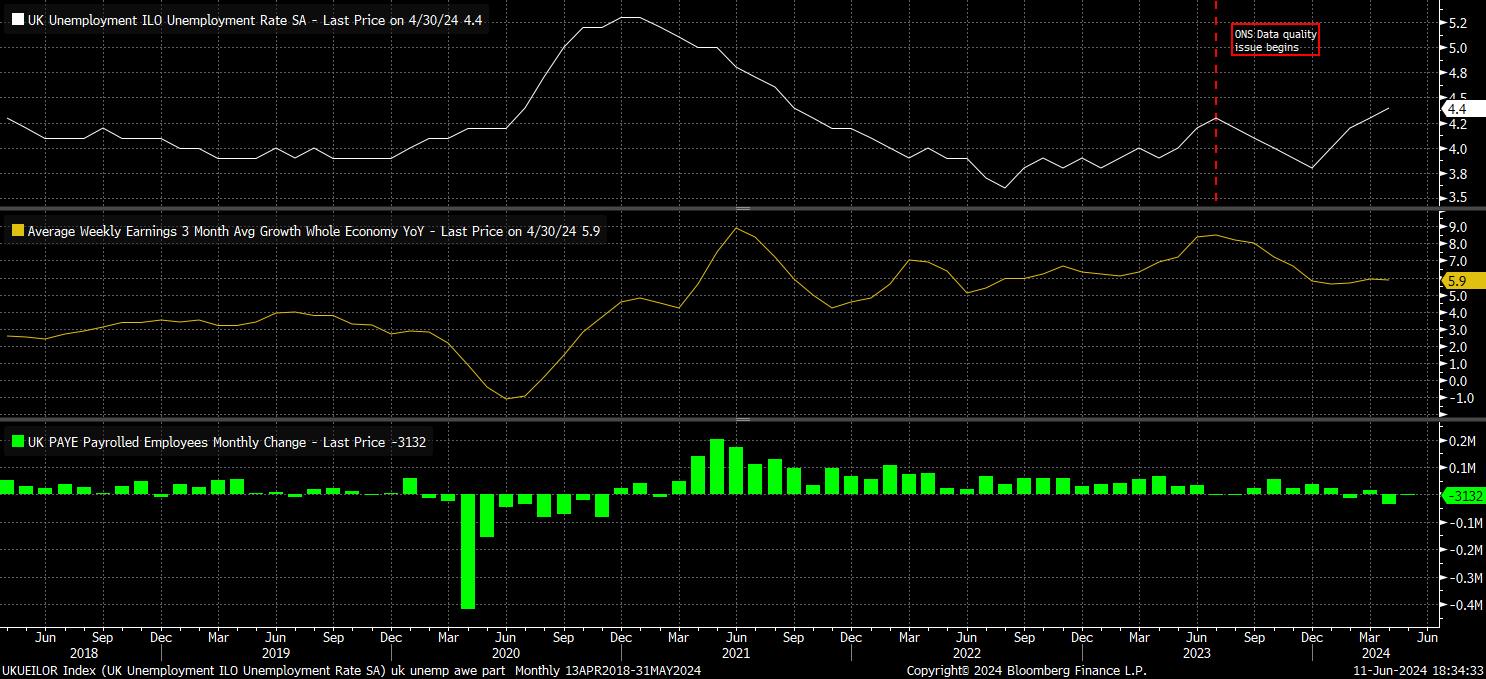

The third, and final, reason for the BoE to hold steady comes from the labour market.

April’s employment report was an incredibly mixed bag, albeit one that sent ‘stagflationary’ signals, and one where the continued rapid pace of earnings growth is likely to cause some further consternation over the stickiness of price pressures.

Headline unemployment rose to 4.4% in the three months to April, the highest such level since September 2021, though the now-standard caveats over the unreliability of the ONS’ data collection must apply. Meanwhile, regular pay rose 6.0% YoY, unchanged from the pace seen a month prior, and continuing to represent a rate of both nominal, and real, earnings growth that is incompatible with a return to the MPC’s 2% target. Clearly, for a group of policymakers seeking to be reassured that price pressures are not becoming embedded within the economy, this is not data they would wish to see, and provides further rationale to hold rates steady this time around.

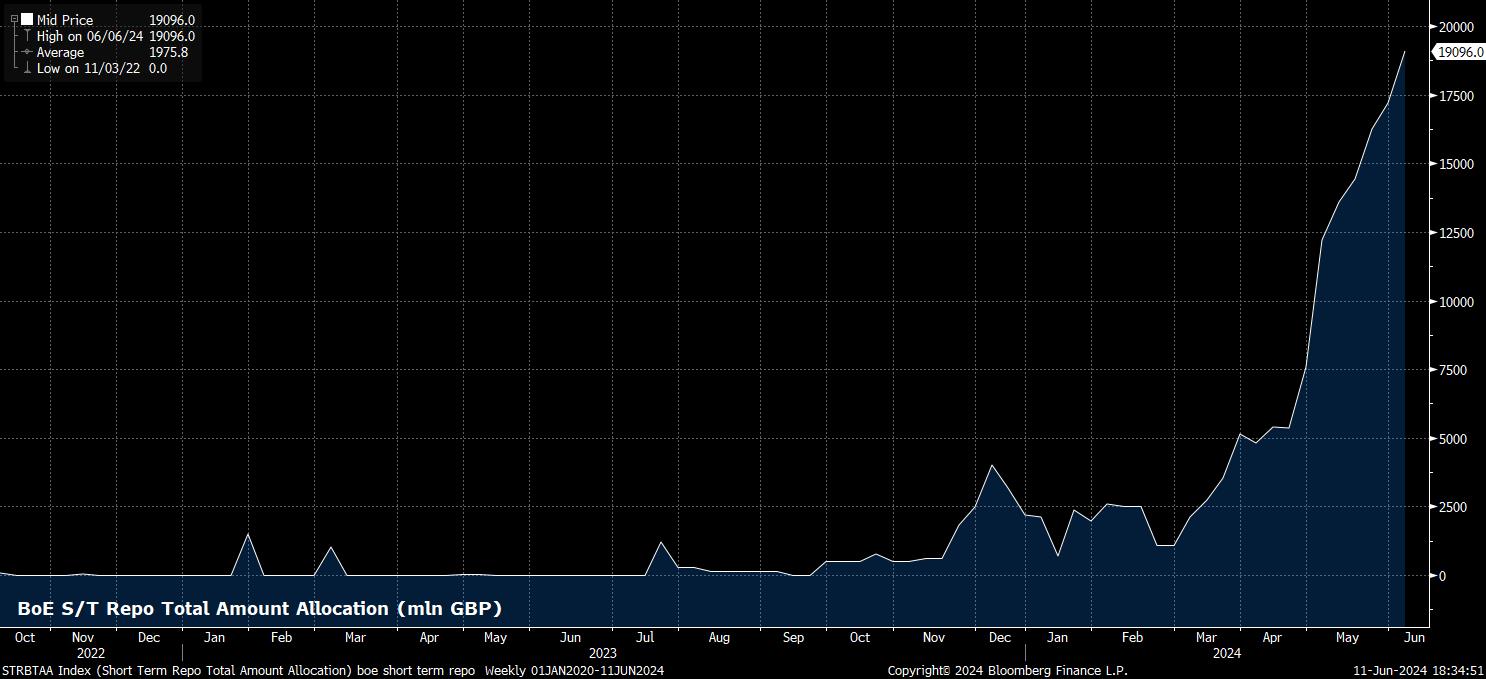

There is, besides the rate decision itself, another area of interest pertaining to the BoE at present. This relates to the recent surge in usage of the BoE’s short term repo facility; usage of which has hit a record high in 7 straight weeks, and now stands at almost £20bln, per the most recent data at the time of writing.

In short, the surge in usage of this facility, designed in 2022 to permit banks access to short-term cash, likely stems from increasingly tight funding conditions, largely stemming from the BoE’s continued programme of active gilt sales, as part of the quantitative tightening process. While no decision is due on QT at this juncture, and the lack of a press conference gives no opportunity for policymakers to explain their current thinking on this matter, it seems likely that, at the annual balance sheet review in September, the MPC decide to active sales, reverting to passive run-off of maturing gilts, in a similar manner to the QT process followed by most other G10 central banks.

The aim here, of course, would be to prevent a significant funding squeeze within UK markets, though this issue does appear to have been encountered much sooner in the QT process than Bank officials had expected, given that gilt holdings currently stand just shy of £700bln, and Governor Bailey’s prior remarks have indicated his estimate for the “steady state” of the BoE’s balance sheet to sit somewhere between £345bln and £490bln.

In terms of markets more broadly, the June MPC meeting seems likely to be something of a non-event, with the prospect of either a rate cut, or a further dovish step, seemingly off the table. Cable, hence, looks likely to remain relatively rangebound, particularly as vol remains rather subdued across G10 FX.

_2024-06-11_18-35-34.jpg)

For the BoE outlook at large, with a June cut now highly unlikely, the first 25bp cut looks set to be delivered at the August MPC meeting, providing incoming inflation data begins to evolve more in line with the Bank’s forecasts. Such a cut, however, is likely to be a split decision among MPC members, with further easing likely to take place at a cautious pace, with just one further cut this year, in November, the most plausible scenario.

Risks, here, however, are biased in a hawkish direction, given recent inflation and labour market outturns.

Related articles

Pepperstone不代表這裡提供的材料是準確、及時或完整的,因此不應依賴於此。這些資訊,無論來自第三方與否,不應被視為建議;或者買賣的提議;或者購買或出售任何證券、金融產品或工具的招攬;或參與任何特定的交易策略。它不考慮讀者的財務狀況或投資目標。我們建議閱讀此內容的讀者尋求自己的建議。未經Pepperstone的批准,不允許複製或重新分發此信息。