CFDs are complex instruments and come with a high risk of losing money rapidly due to leverage. 72.2% of retail investor accounts lose money when trading CFDs with this provider. You should consider whether you understand how CFDs work and whether you can afford to take the high risk of losing your money.

- English

- Italiano

- Español

- Français

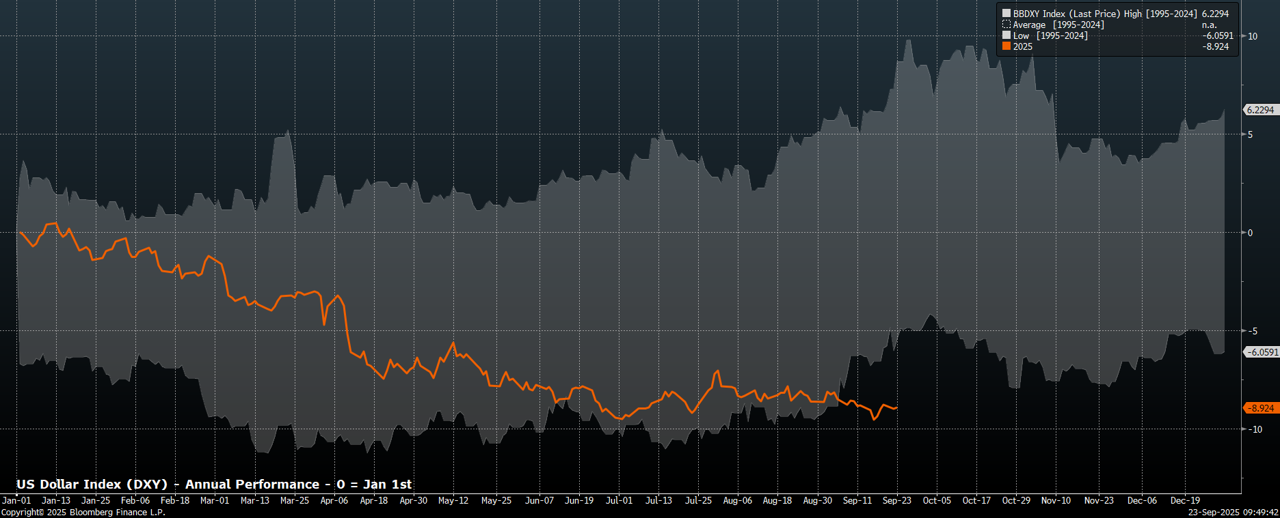

Since the turn of the year, the greenback – per the dollar index (DXY) – has fallen almost 11%, comfortably the worst performance, at this point in a calendar year, in the last three decades, and in fact the second worst such performance 1972, just after the Bretton Woods system was, effectively, brought to an end.

While the DXY has its flaws, namely a significant weighting towards the EUR, other metrics of the greenback’s performance paint a similarly downbeat picture. Bloomberg’s dollar index (BBDXY), for instance, which tracks the buck’s performance on a trade-weighted basis, is down about 9% on the year, and has also chalked up its worst performance at this point in a year for at least 30 years.

Drilling down a little further, against an expanded basket of major currencies, the USD trades positive YTD against just the IDR, INR, TRY, and ARS, having lost ground against almost everything else one could think of. Furthermore, it would frankly have been difficult not to advance against those four, given Indonesia’s recent embarkation on an ‘unorthodox’ fiscal/monetary mix, the INR having slumped to record lows, Turkey remaining something of a ‘basket case’, and the free(ish) floating nature of the ARS.

With all that in mind, it’s important to consider why the buck has been so soft over the last nine months.

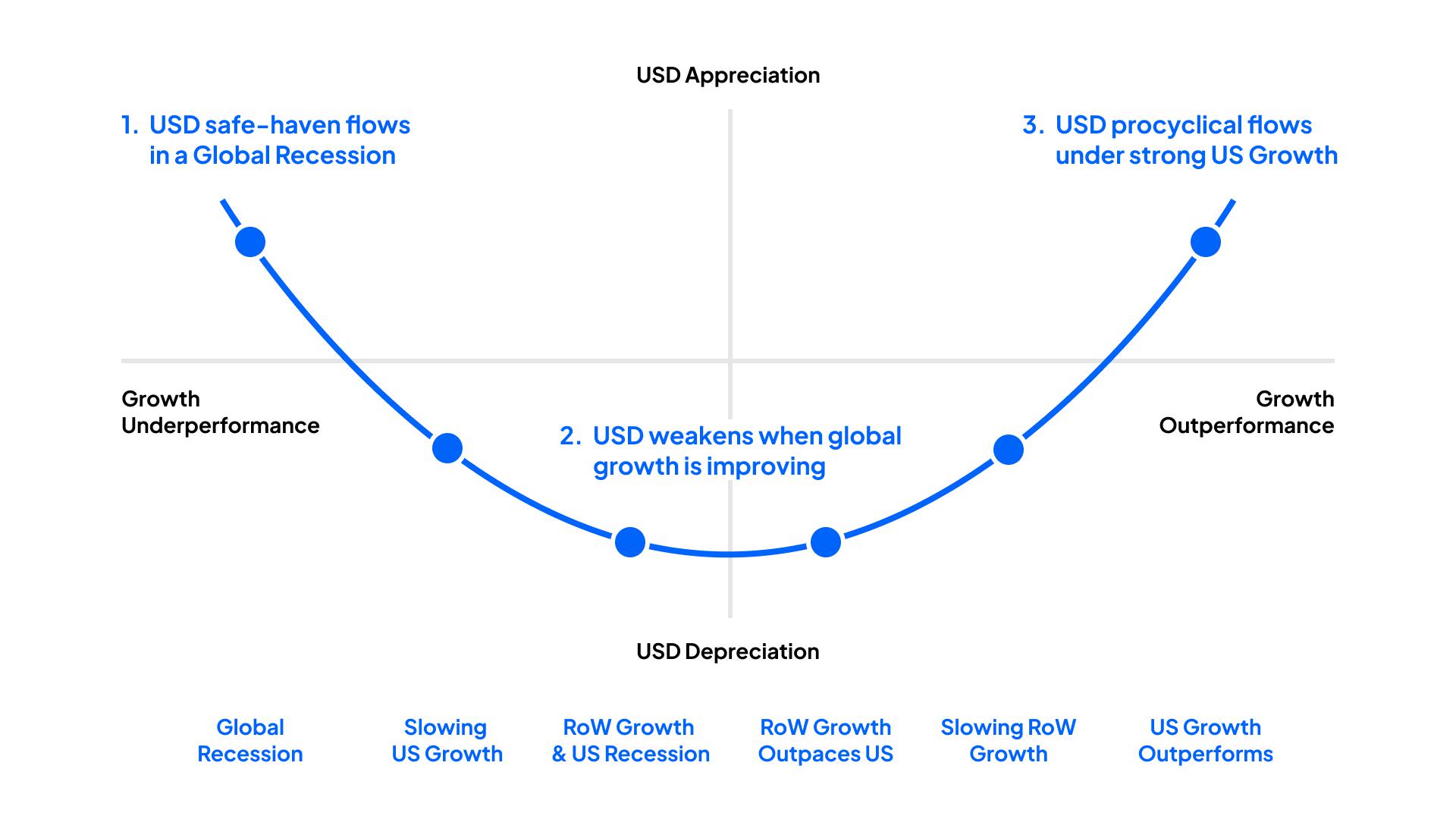

Perhaps the most obvious, and certainly one of the most significant, drivers of this weakness have been a vast amount of capital outflows from the USD, as investors became spooked by the volatile and uncertain nature of the Trump Administration’s policies. This, to recap, encompassed anything and everything from the ever-changing nature of trade policies, to continued attempts at eroding the Fed’s monetary policy independence. At the same time, more convincing investment cases started to emerge elsewhere, as the BoJ continued to tighten policy, and as European governments delivered the fiscal stimulus that participants, and policymakers, had spent years longing for.

Together, all this created something of a perfect storm for the greenback, in which the idea of ‘US exceptionalism’ faded rapidly, not only as a result of the stateside growth ‘catching down’ to that of DM peers, but as growth elsewhere finally showed signs it may ‘catch up’.

Now, though, tentative signs are emerging that the buck might well be starting to bottom out. Recent price action helps to support this idea, with the DXY having spent the majority of the last three months consolidating, moving sideways in a relatively tight 96.40 to 99.20 band.

_2025-09-23_09-50-39.jpg)

Though some of this consolidation, of course, owes to exhaustion on the part of dollar bears, it is also fair to say that the aforementioned macro headwinds that had buffeted the buck in H1, have now begun to subside.

Clearly, a considerably calmer tone has begun to prevail on the trade front, as the daily rhythm of fresh tariffs being announced on ‘Truth Social’ has instead given way to trade deals being struck across the globe, either permanent understandings, or truces such as that agreed with China. In any case, this has contributed to a considerable degree of uncertainty, which had clouded the outlook, beginning to lift.

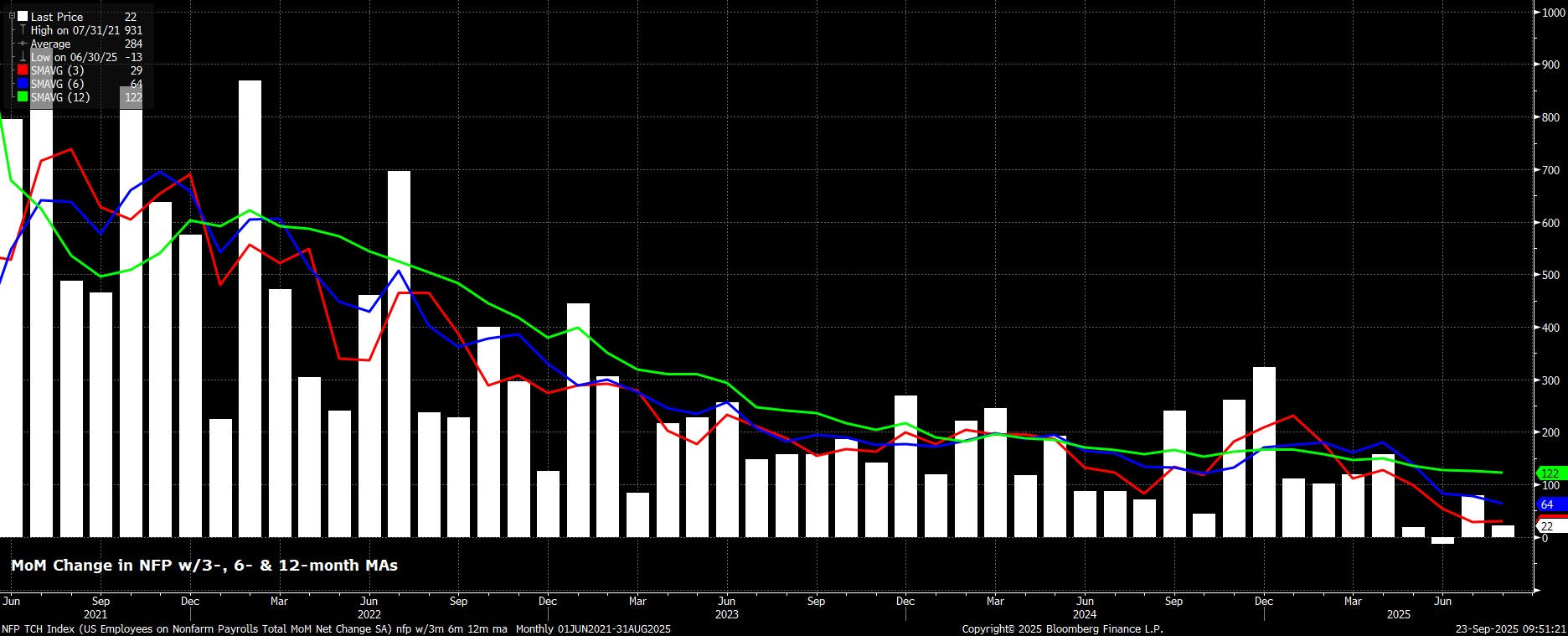

In light of this, I remain keen to frame some of the recent softness in incoming US labour data – e.g., a cycle high 4.3% unemployment rate, and the 3-month average of job gains falling well below the breakeven pace – more akin to an economy adjusting to a ‘new normal’, as opposed to one that is starting to crack. In many ways, the imposition of tariffs in early-April, and following shifts in trade policy over the subsequent few months, are akin to a ‘man-made natural disaster’, if you’ll forgive the contradiction in terms.

What I mean, here, is that the economy, chiefly the labour market, is hit with an unexpected and significant external shock, to which participants must react, before then adjusting to what is left behind once the disaster in question passes. In this context, April was the hurricane, June/July/August were the adjustment months, and we’re now at the stage where some degree of economic normality may well begin to return as the disaster blows over.

Supporting this idea is the fact that, under the surface, the US economy remains surprisingly resilient.

Consumer spending has proved the engine of US growth for some time now, and remains robust, with control group retail sales having risen for 4 months in a row, including three straight months at a clip faster than 0.5% MoM, while personal spending – per the PCE report – has risen in all but one month this year, with that sole decline having come way back in January.

That, coupled with business investment remaining solid, helped largely by ever-increasing AI-related capex, a rebuild in inventories that were drawn down shortly after ‘Liberation Day’ in April, as well as a normalisation in the net exports component as the aforementioned tariff front-running shakes out of the data, has pushed the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow metric to estimate third quarter growth at 3.3% annl. QoQ, underlining how there is little structurally wrong with the US economy at this juncture.

Of course, the one missing piece of the puzzle, so far, is the monetary backdrop, which is about to become considerably looser, considerably quicker than most participants had expected, in the aftermath of the dovish 25bp cut delivered at the September FOMC confab. In short, the Fed’s strategy can now be summed up as ‘run it hot’ – as policymakers seen to lean in aggressively to support the labour market, and economic growth more broadly.

While the ‘cost’ of this approach is, likely, higher inflation in the short-term, tilting the reaction function so heavily towards labour market developments does now firmly tilt the balance of risks to the US economy to the upside, arguably for the first time this year, particularly considering the powerful ‘Fed put’ (400bp of cuts and a balance sheet at just 21% of GDP) that could be activated if/when required.

Looking ahead, there are further reasons to think that the worst may be behind the greenback, especially as participants increasingly turn their attention towards 2026. Next year, the economy should begin to feel the stimulative effects of the ‘One Big Beautiful Bill Act’ (OBBBA) which was signed into law this summer, as a host of personal tax deductions, plus numerous initiatives aimed at boosting business investment and personal consumption also go into effect. In addition, inflows from the investments pledged as part of various US-RoW trade deals could well begin to materialise, while the Trump Admin may begin to switch focus, now that trade and taxes are ‘done’, towards the promising deregulation agenda that was parked earlier this year.

Speaking of politics, one must also consider that, next November, the US heads to the polls for midterm elections. As we approach polling day, it would only be natural for the Admin to seek to, at the very least, ensure that growth remains underpinned, if not embark on an attempt to juice things more aggressively. Think of it as a ‘Trump put’, if you will, coupled with a ‘Fed put’ in the mix as well.

Those factors, combined, all support the idea that risks to the US outlook are now tilted to the upside, and that risks to the greenback are tilted in the same direction, with participants currently far too pessimistic on both. One must also look elsewhere, as the story of a robust US economy contrasts starkly with other DMs – the UK, which slips deeper into a fiscal ‘doom loop’ by the day; the eurozone, which remains mired in political instability and its own fiscal woes; Japan, where the BoJ seem to always find an excuse not to tighten further; and, China, which is still stuck in a debt-deflation spiral with both monetary and fiscal policy pushing on a string.

All in all, then, this shifting balance of risks suggests that a return to ‘US exceptionalism’ looks to be on the cards, potentially acting as the catalyst to confirm that the greenback has bottomed out, as markets return to the right hand side of the ‘dollar smile’.

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.