CFDs are complex instruments and come with a high risk of losing money rapidly due to leverage. 72.2% of retail investor accounts lose money when trading CFDs with this provider. You should consider whether you understand how CFDs work and whether you can afford to take the high risk of losing your money.

- English

- Italiano

- Español

- Français

Macro Trader: The BoE May Be Doing More Harm Than Good

While Bank Rate was held steady, as expected, at the September meeting, remaining at 5.00% after the ‘finely balanced’ decision to deliver this cycle’s first cut back in August, there are some signs beginning to emerge that the MPC may be both behind the curve, and out of sync with their DM peers.

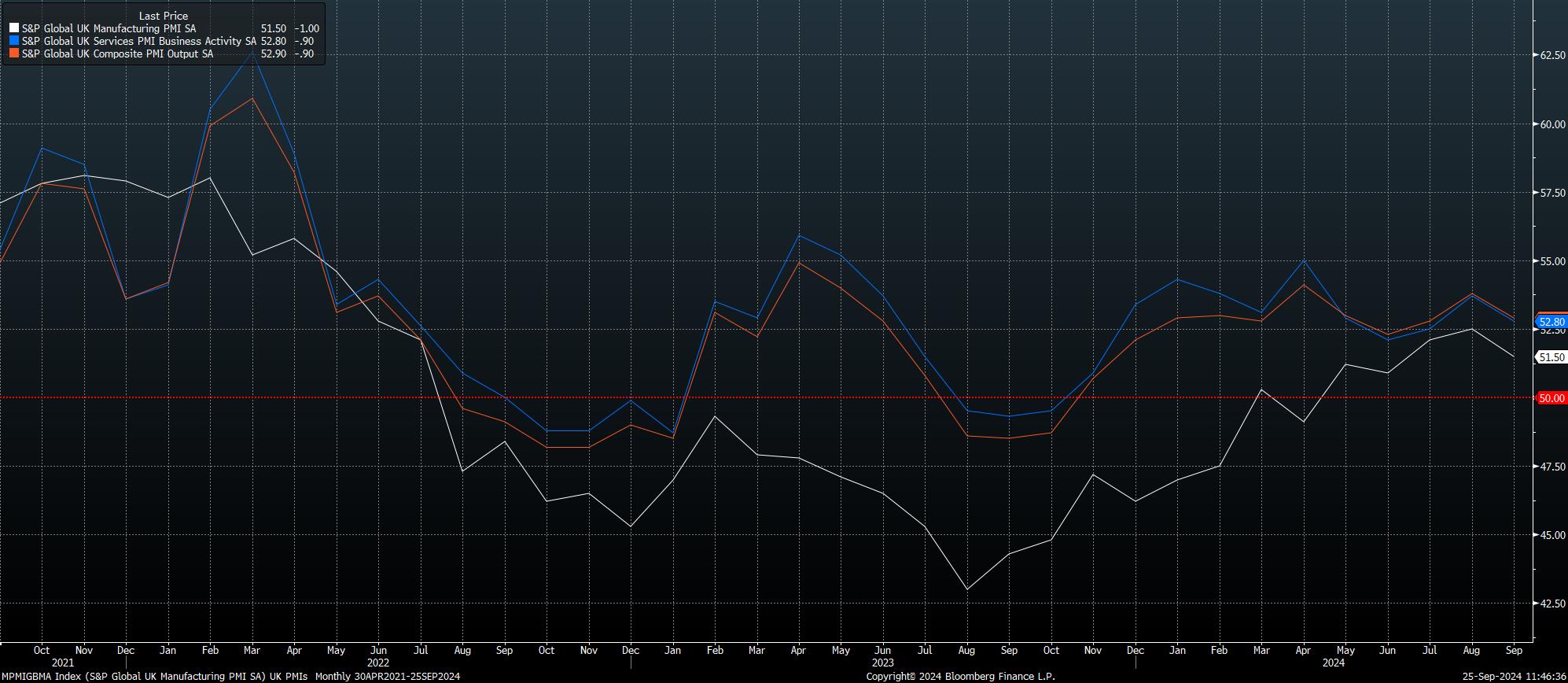

This week’s PMI surveys, for example, delivered a dose of pessimism. While all three – manufacturing, services, and composite – gauges remained north of the 50 mark, implying continued expansion, the pace of said expansion moderated for the first time since June, with the manufacturing index a particular concern, having slipped to a 3-month low.

Digging into the PMI report, there is further cause for concern over the BoE’s present stance. Price pressures, for instance, continued to fade, with inflation in the private sector falling to aa 42-month low in September, per S&P Global’s survey. Concurrently, employment growth in the private sector slowed for the second straight month, to its slowest level since June – a slowdown which, in large part, can be attributed to increased caution amid elevated uncertainty ahead of the Budget on 30th October.

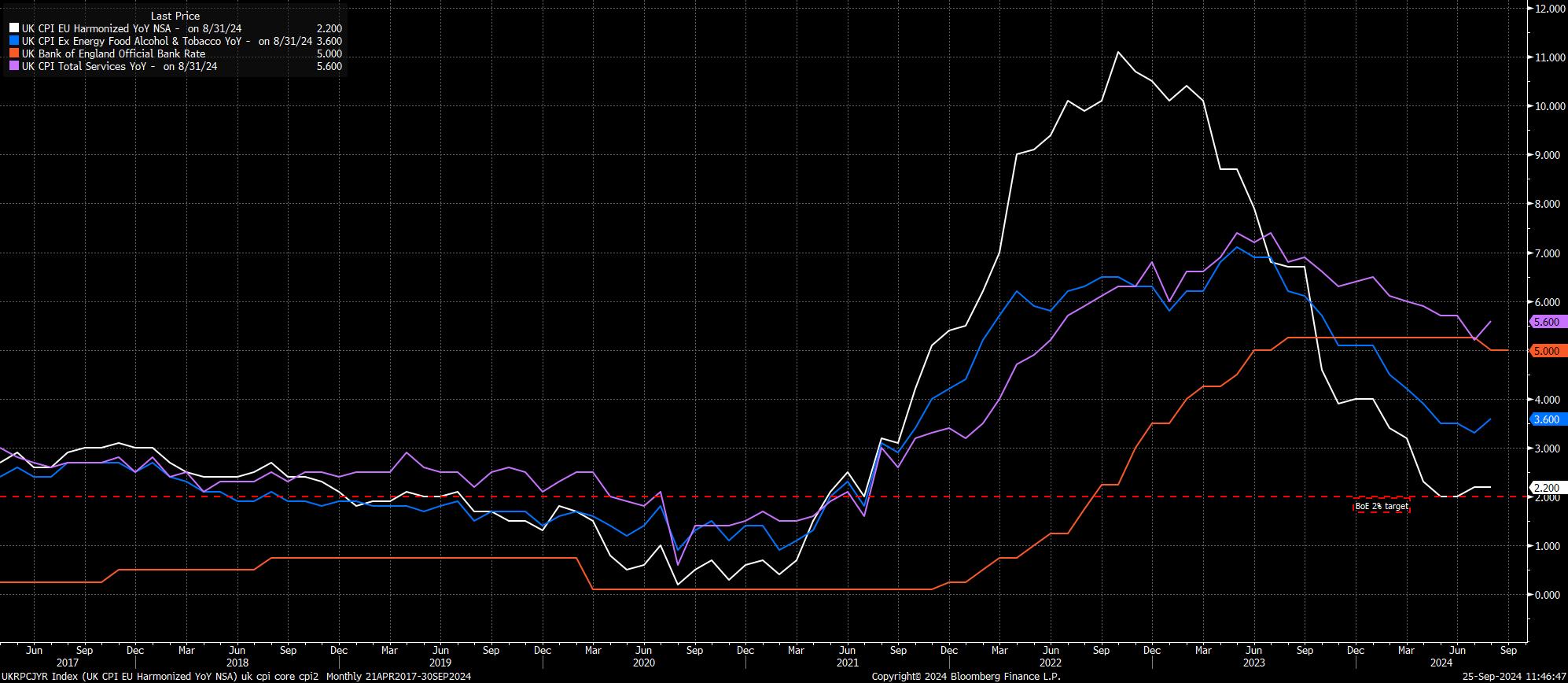

Of course, one must recall that the MPC’s mandate is not growth, but ensuring price stability, as measured by 2% headline inflation. Here, the hawks would point to the need for further progress to be made before further Bank Rate cuts are delivered, particularly after the uptick in both core and services CPI metrics last month. On the other hand, with these upticks driven largely by base effects from 2023, the MPC’s doves would flag that, with headline CPI as near as makes no difference at target, Bank Rate should return to a neutral level in much shorter order.

In truth, though, it is not Bank Rate that is the issue, but the MPC’s decisions when it comes to the balance sheet.

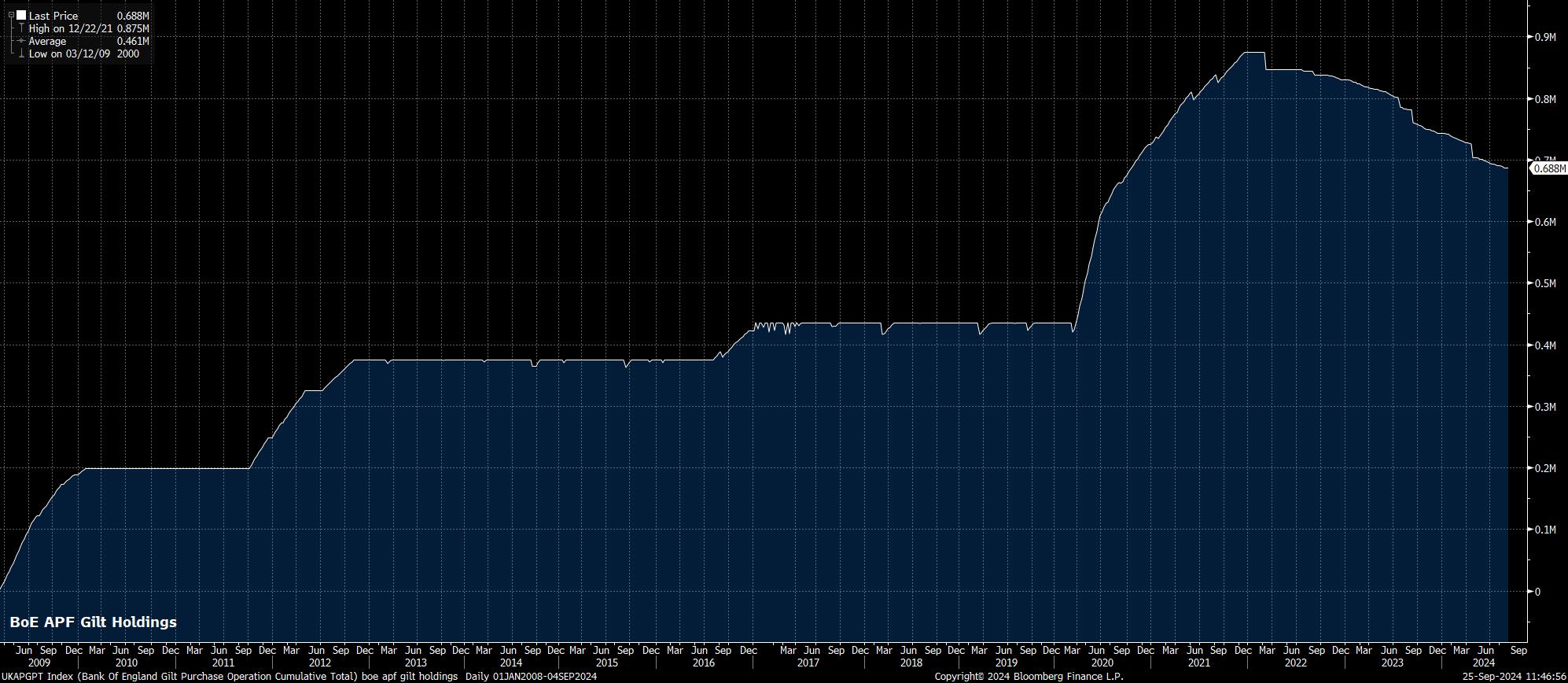

At the September MPC, the Committee voted unanimously to reduce the BoE’s stock of gilt holdings by a further £100bln over the next 12 months, unchanged from the pace seen in the prior two years, since quantitative tightening began in 2022. The composition of this run-off, however, has changed notably from last year. Due to a whopping £87bln worth of maturing gilts passively rolling off the balance sheet, active sales, which last year ran to just over £50bln, will drop to around £13bln this year.

There are a few issues here.

Firstly, at a very high level, the BoE’s continued quantitative tightening process, in keeping with that conducted by other G10 central banks, is resulting in the two primary policy levers working in opposite directions. While Bank Rate is reduced, loosening the policy stance, continued balance sheet run-off has the effect of tightening said stance, thus lessening the overall impact of the aforementioned Bank Rate cuts.

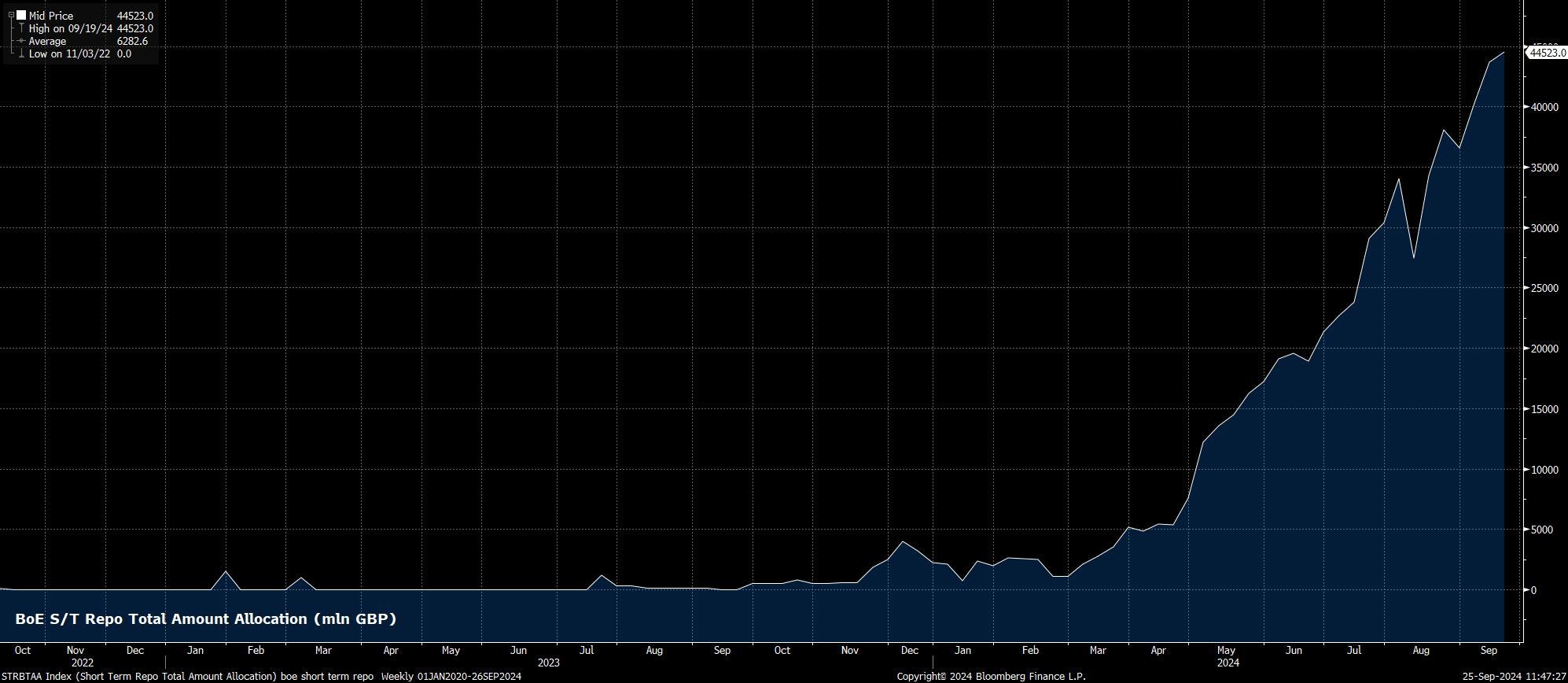

Secondly, by continuing to shrink the size of its balance sheet, the Bank increasingly run the risk of conditions within the UK finance system becoming too tight, raising the possibility of a funding squeeze. This can be seen via the BoE’s weekly short-term repo operations, with usage of said facility continuing to surge, hitting a record high on a near-weekly basis, with repo rates also remaining elevated.

Perhaps the biggest issue, here, however, is on the fiscal side of proceedings.

The ongoing QT process creates issues for the Treasury, who must indemnify the BoE against any losses that are incurred under the programme (profits are passed the other way). This means that, as the BoE crystalise losses from active gilt sales, Government losses mount. Further complicating matters is that the OBR – the god-like authority which runs the rule over Budgets each year – must assume a certain path of gilt sales when producing their forecasts, meaning that assumptions on the path of QT can, and will, have a significant impact on the degree of ‘headroom’ provided to the Chancellor when crafting fiscal policy.

That headroom, for what it’s worth, is calculated as the difference between projected spend, and the limit imposed by the fiscal rules – presently, that net borrowing must not exceed 3% of GDP in the 5th year of the OBR’s forecast, and that public sector net debt must be falling as a proportion of GDP by the same year.

With fiscal headroom having been just £9bln in the March 2024 OBR forecasts, the new Government having already outlined plans to significantly raise taxes and cut spending, plus assumptions on the future path of QT being worth a swing of +/- £15bln in fiscal space, the impact of this rather academic subject quickly becomes clear.

Though Chancellor Reeves could well tweak the fiscal rules in five weeks’ time, excluding the BoE’s QT programme from the calculation, that is unlikely to alter the general theme of the Budget – one of a dramatic fiscal tightening. Risks are elevated that such a tightening could choke off economic growth, in turn posing a significant downside risk to the GBP if a further loss of economic momentum were to force policymakers into a more dramatic dovish shift.

Related articles

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.