CFDs are complex instruments and come with a high risk of losing money rapidly due to leverage. 72.2% of retail investor accounts lose money when trading CFDs with this provider. You should consider whether you understand how CFDs work and whether you can afford to take the high risk of losing your money.

- English

- Italiano

- Español

- Français

Big Themes For 2024 – What The Year May Bring For The UK Economy

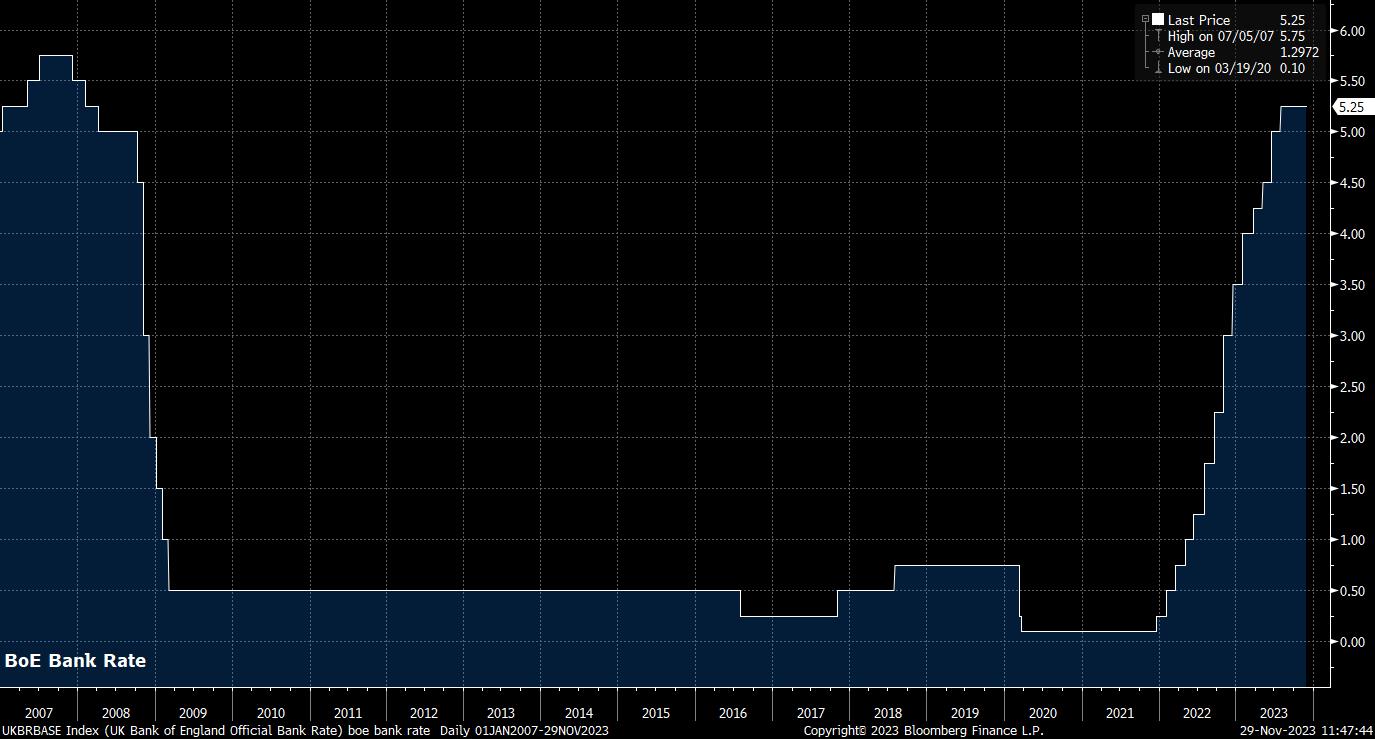

As noted, the Old Lady’s tightening campaign continued in earnest throughout 2023, including the surprise delivery of a 50bp hike back in June, after an unexpected, renewed surge in headline inflation. Said tightening cycle has now, however, come to an end, with Bank Rate at 5.25%, its highest level since mid-2008, as the MPC adopt what Chief Economist Pill has coined a ‘Table Mountain’ approach to monetary policy.

Such an approach is, put simply, a different way of picturing the ‘higher for longer’ stance that almost all other G10 central banks are also taking to monetary policy in an attempt to bring inflation back to target and, if possible, engineer a soft landing. One of the key questions for the UK economy, and UK investors, next year will be the duration of the “extended period”, to quote various MPC members, that Bank Rate will need to remain at terminal in order to bring inflation back to the 2% target. Furthermore, there remain question marks over whether remaining in a restrictive stance for such a period will, ultimately, tip the economy into recession.

Before getting to the growth side of things, inflation must be addressed. While the disinflation process is now well underway, price pressures within the UK economy – as has proved the case during numerous previous bouts of inflation – remain more intense than elsewhere in developed markets, with headline CPI still over double the MPC’s 2% aim.

There are numerous factors contributing to this, with the ‘energy price cap’ system for calculating household fuel prices actually having acted to put a floor under inflation measures for much of the year, though the impacts of this are now beginning to fall out of the data. That said, although OFGEM’s price cap has fallen YoY, the average household is likely to spend more on energy bills in 2024 than a year prior, owing to a sharp reduction in government bill support, leading to further constraints on disposable income and discretionary spending.

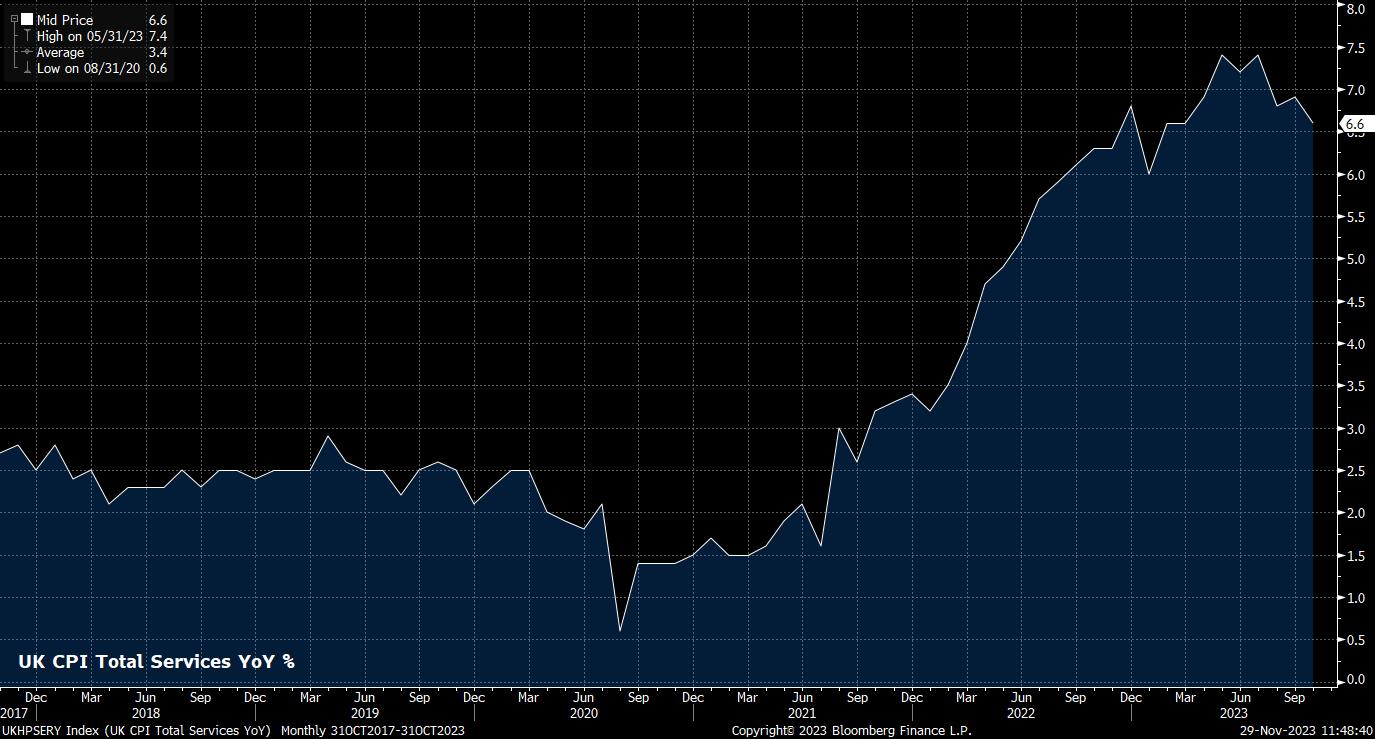

In any case, the MPC’s principal concern lies with services inflation, which is where the most persistent price pressures appear to lie. Total services CPI remained north of 6% YoY in October, having remained above that level for well over a year now, evidencing the ‘stickiness’ of price pressures which are increasingly embedding themselves within the UK economy. Of all inflation gauges, and other metrics, that policymakers track, a significant retreat in services inflation is likely to be required before the notion of rate cuts is debated on Threadneedle Street.

Signs of a peak in services inflation are, though, beginning to emerge. Slack is, slowly but surely, creeping into the labour market, with unemployment having risen to 4.2% in the three months to September, up from a 3.5% cycle low seen in mid-2022; although, this data must be taken with a pinch of salt, given the ONS’ recent switch to an ‘experimental’ calculation method, owing to concerns about the reliability of the information contained in the Labour Force Survey.

No matter the reliability of the figures, the rise in unemployment, and the return of the vacancies-unemployed ratio to more levels, are yet to be accompanied by an easing in earnings growth. Total regular pay continues to grow at a pace of roughly 8% YoY, a rate that is clearly incompatible with a return to the BoE’s 2% inflation objective. While much of this pace has been explained by one-off factors, such as bonuses paid to civil servants and healthcare workers, the persistence of this elevated level of wage growth, along with recent surveys indicating expectations among firms that wage pressures will remain intense, suggest more is at play here.

Altogether, this suggests that in order for wage to return rapidly to a level more compatible with 2% inflation, a further sharp rise in unemployment will be required, likely as a result of a relatively significant, and synchronised, recession. Without such an eventuality, earnings growth is set to remain elevated, leading to services inflation remaining sticky, extending the duration that the MPC is likely to remain at the top of ‘Table Mountain’.

Though none of the BoE, OBR, or sell-side consensus call for a recession next year, UK economic growth is likely to remain, at best, lacklustre. While consumer confidence, and real income growth, should both rise further as the disinflation process continues throughout 2024, the positive effect of these factors is likely to be counter-acted by the continued pass-through of the BoE’s tightening into higher mortgage rates, in addition to a potential desire to rebuild excess savings balances that have been rapidly drawn down since the pandemic.

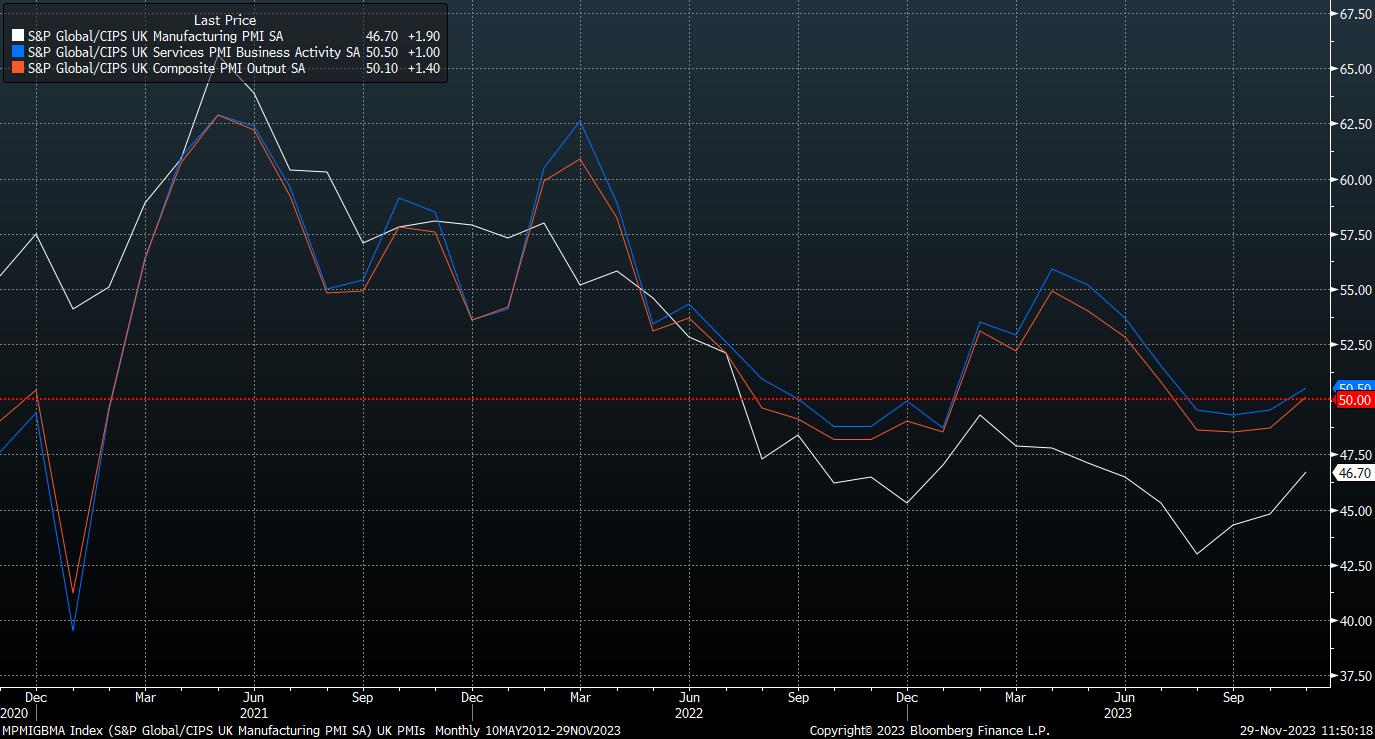

The effective stagnation currently implied by incoming PMI surveys looks set to continue through much of the coming twelve months, though rate-sensitive areas such as the housing and construction sectors are likely to bear the brunt of any more significant loss of economic momentum.

While on the subject of growth, a degree of fiscal loosening is almost certain to be delivered prior to the next general election, which must be held by January 2025, though is widely expected to come next autumn. Though the public finances remain relatively fragile, and the ‘mini-budget’ fallout of 2022 remains fresh in the minds of most, pre-election tax cuts are likely in the March Budget.

At the margin, such tax cuts will likely provide a fillip to consumer spending over the summer months, though the fiscal headroom to cut significantly remains relatively limited. Either way, any such positive impact is likely to prove a relatively short-lived sugar rush, with growth likely to run below potential for the foreseeable future, along with a potential change in government likely leading to a renewed fiscal tightening in the next Parliament.

Putting all of this together produces a relatively complex outlook for the GBP as we look to the year ahead.

_2023-11-29_11-51-47.jpg)

The GBP bull case rests largely on the BoE proving a hawkish outliner among G10 central banks, looking through economic weakness as inflation remains substantially above target, resulting in Bank Rate remaining ‘higher for longer’ than G10 peers, widening UK-RoW spreads, and supporting the pound. On the other hand, the bear case is built upon market participants focusing increasingly on growth dynamics, taking a dim view of the UK’s continued anaemic output, amid concerns over potential ‘stagflation’.

The balance of risks, given the market’s current focus on rate differentials, would lean towards the former, particularly as the greenback moves increasingly towards the middle of the ‘dollar smile’.

Related articles

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.