CFDs are complex instruments and come with a high risk of losing money rapidly due to leverage. 72.2% of retail investor accounts lose money when trading CFDs with this provider. You should consider whether you understand how CFDs work and whether you can afford to take the high risk of losing your money.

- English

- Italiano

- Español

- Français

Big Themes For 2024 – What The Year May Bring For The Eurozone Economy

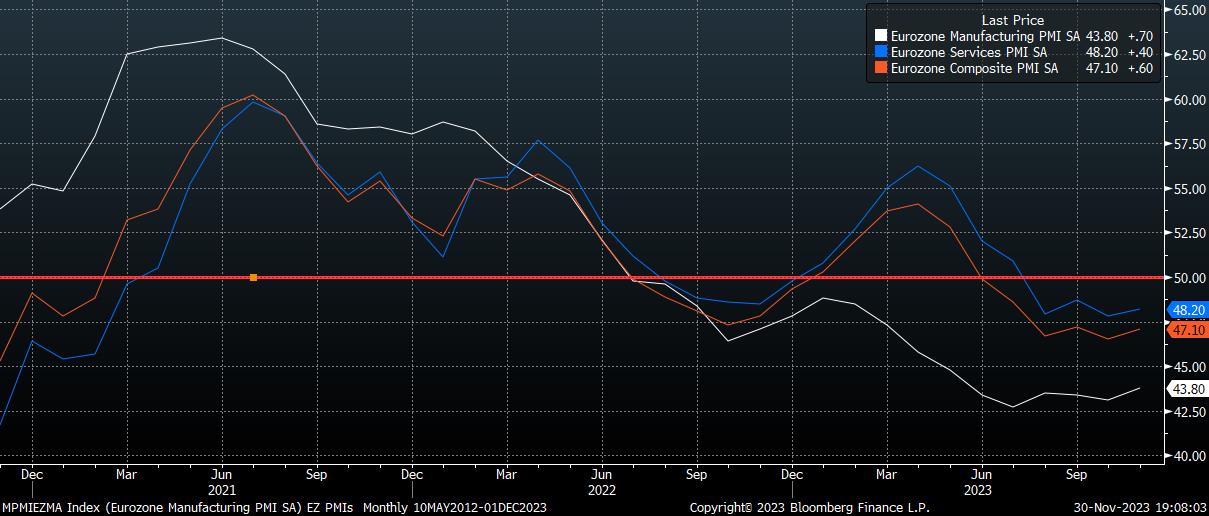

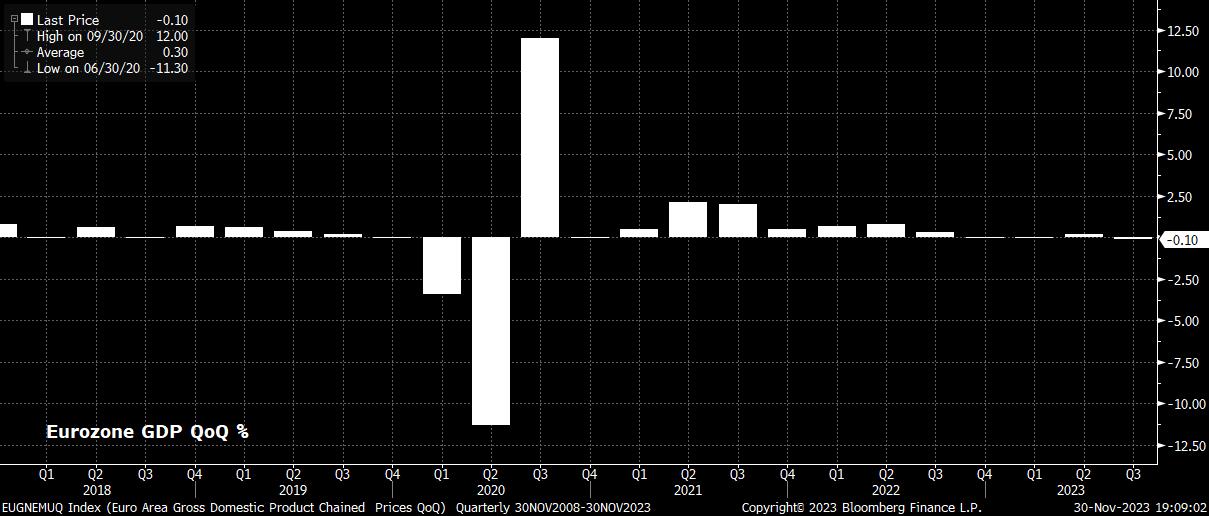

The year that’s passed is perhaps one of missed opportunity for the eurozone, with the aversion of an energy-induced winter recession surprising most, but resilience in the early part of the year being followed by a slump in economic activity, rather than any form of significant bounce. The most recent PMI surveys – both at a bloc-wide, and national level – epitomise this well, with fears of the eurozone dipping back into recession making a resurgence as the year draws to a close.

At best, incoming PMIs point to stagnation, which might allow the bloc’s economy to continue muddling through for some time, until the point arrives at which inflation has returned to the 2% target, and the ECB are prepared to loosen policy and potentially provide some relief to the growth side of the equation.

More realistically, however, these leading indicators point to risks being heavily tilted to the downside in the early stages of 2024, particularly with Europe’s ‘engine room’ – the German economy – struggling more than most peers. Of course, this must be added to the stiff external headwinds that the bloc continues to face, with demand from China remaining anaemic, and geopolitical tensions remaining elevated, along with the long-running structural issues that have dogged the eurozone for some time now.

In short, there is relatively little in terms of good news on the growth front. The external environment remains poor, leading indicators weak, credit appears soft, a co-ordinated bloc-wide fiscal policy remains elusive, and monetary policy remains tight, with the full effects of the ECB’s hiking cycle still feeding through into the economy. Hence, another year of sluggish, and sub-potential, growth likely awaits.

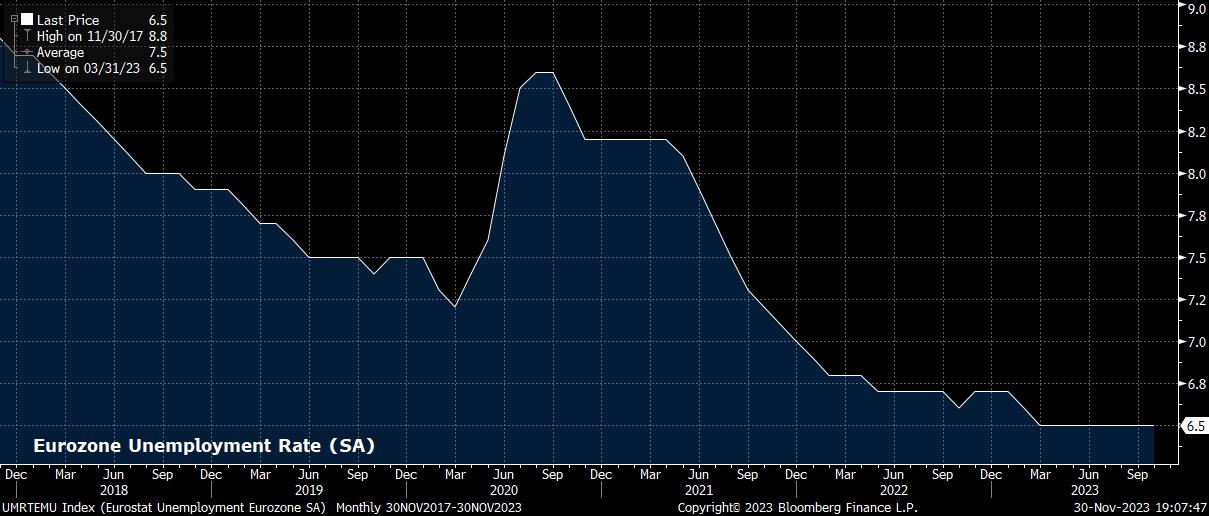

Still, the bloc may avoid a deeper downturn owing to the relatively solid nature of the eurozone labour market. In contrast to developments in other DM economies, there have been scant signs of any softening in labour conditions within the bloc of late, with unemployment having hovered around 6.5% all year, and private sector firms continuing to report difficulties in recruiting.

A more significant recession would likely require a sharper softening in the labour market, which thus far data does not nod towards; while decidedly possible, such a scenario seems unlikely at present. Consequently, household incomes should remain relatively solid, increasing in real terms as inflation fades, to some degree underpinning spending and aiding the ailing services sector.

Of course, the upside to this dismal pace of economic expansion is that it will likely lead to a more rapid disinflationary process than that seen in other G10 economies, while also raising the prospect of the ECB delivering so-called ‘insurance’ cuts, if policymakers see fit, in order to stave off a deeper and much more damaging downturn.

While OIS currently fully prices the first 25bp deposit rate cut for next April, the Governing Council appear likely to want to wait for more information and certainty that inflation is on a path back to 2% before delivering the first cut. This is especially important given the likely upward inflationary impulse that will be seen in Q1 24, though risks to eurozone inflation are skewed to the downside at this juncture, given the rocky growth outlook, and the dismal demand-side landscape.

Overall, money markets currently imply around 100bp of cuts from the ECB in 2024 which, while broadly in line with the magnitude of cuts priced for the FOMC, seems much more likely to be delivered, given the manner in which both growth and inflation risks point to the downside.

Looser policy, however, may prove to be something of a blessing for the eurozone economy, given that a rapid lowering of the deposit rate would help to sharply improve the bloc’s growth drivers. In any case, of all G10 central banks, the ECB appear the most likely to return rates to a neutral level in the shortest order, particularly in the continued absence of a co-ordinated fiscal policy across the bloc.

Considering the market implications of this outlook is somewhat complex. On the one hand, all signs point to a relatively dismal 2024 for the eurozone, with sluggish growth momentum set to continue, leading the ECB to loosen sooner, and at a more rapid pace, than their G10 peers. However, on the other hand, a significant degree of this pessimism is likely already priced, while the US economy ‘catching down’ to its DM peers may somewhat limit the impact of any negative growth surprises.

Nevertheless, with risks facing the economy tilted firmly to the downside, one must logically conclude that risks to the common currency are also tilted in the same direction, particularly as the year comes to a close with EUR/USD trading close to the 1.10 handle once more. The pair has been epitomised by relatively rangebound trading in recent times, and such conditions may well continue for some time yet.

_Daily_01_2023-11-30_19-06-29.jpg)

Related articles

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.