- English

- 中文版

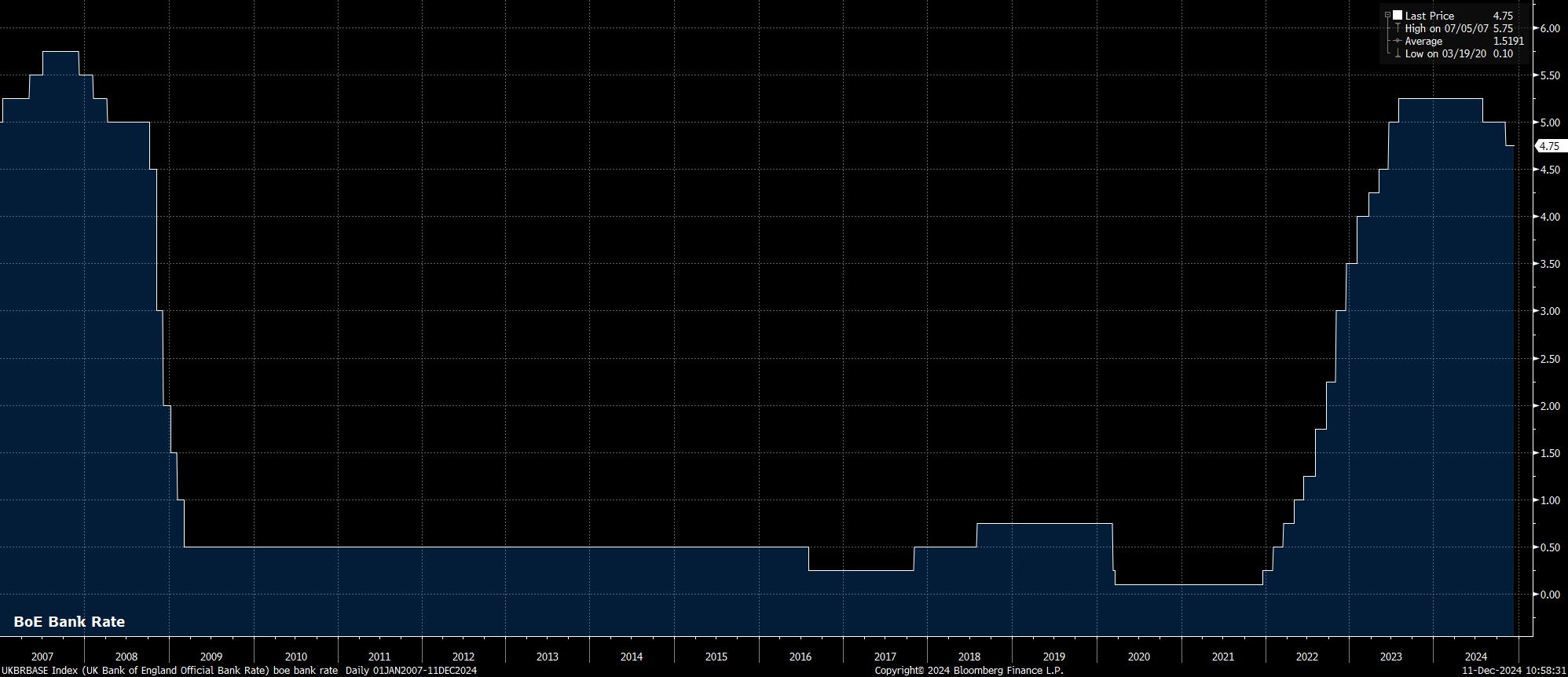

As noted, the MPC are set to leave Bank Rate unchanged at 4.75% at the conclusion of the December meeting, resulting in 2024 having seen just 50bp of easing, as policy continues to normalise slowly but steadily. Money markets, per the GBP OIS curve, imply a 95% chance of policymakers standing pat, though fresh employment and inflation reports are due just before the MPC meet.

The decision to hold rates steady is, however, unlikely to be a unanimous one among the 9-member MPC. Uber-dovish external member Dhingra is, once again, likely to dissent in favour of a 25bp cut, having remarked recently that the MPC “should be easing policy more”. This view, though, is not one that is shared by her colleagues, who continue to favour a more “gradual” approach to policy easing.

In fact, for once, there is actually great diversity of views among MPC members – some, like Dhingra, calling for faster easing; the ‘core’ of the Committee calling for a gradual approach; and others, like external member Mann, who continue to flag upside risks to the inflation outlook. No groupthink accusations can be levelled here!

The nub of all that, though, is that the MPC are likely to form a consensus around holding rates steady, most likely via an 8-1 vote in favour of such action, with Dhingra the lone dissenter.

Accompanying said decision should be a policy statement that is broadly unchanged from that issued after the November meeting. Consequently, the MPC should reiterate that a “gradual” approach to easing remains appropriate, while also flagging a continuation of the present data-dependent stance, with a particular focus on the “risks of inflation persistence”.

Said “gradual” pace is likely to take the form of quarterly 25bp cuts going forwards, a view reinforced by recent comments from Governor Bailey, and external MPC member Taylor. Money markets already broadly reflect such a policy path, with the GBP OIS curve pricing 22bp of easing by February, and just over three cuts by next November.

Of course, the MPC continue to grapple with an uncertain economic backdrop, and one that displays increasing evidence of ‘stagflation’.

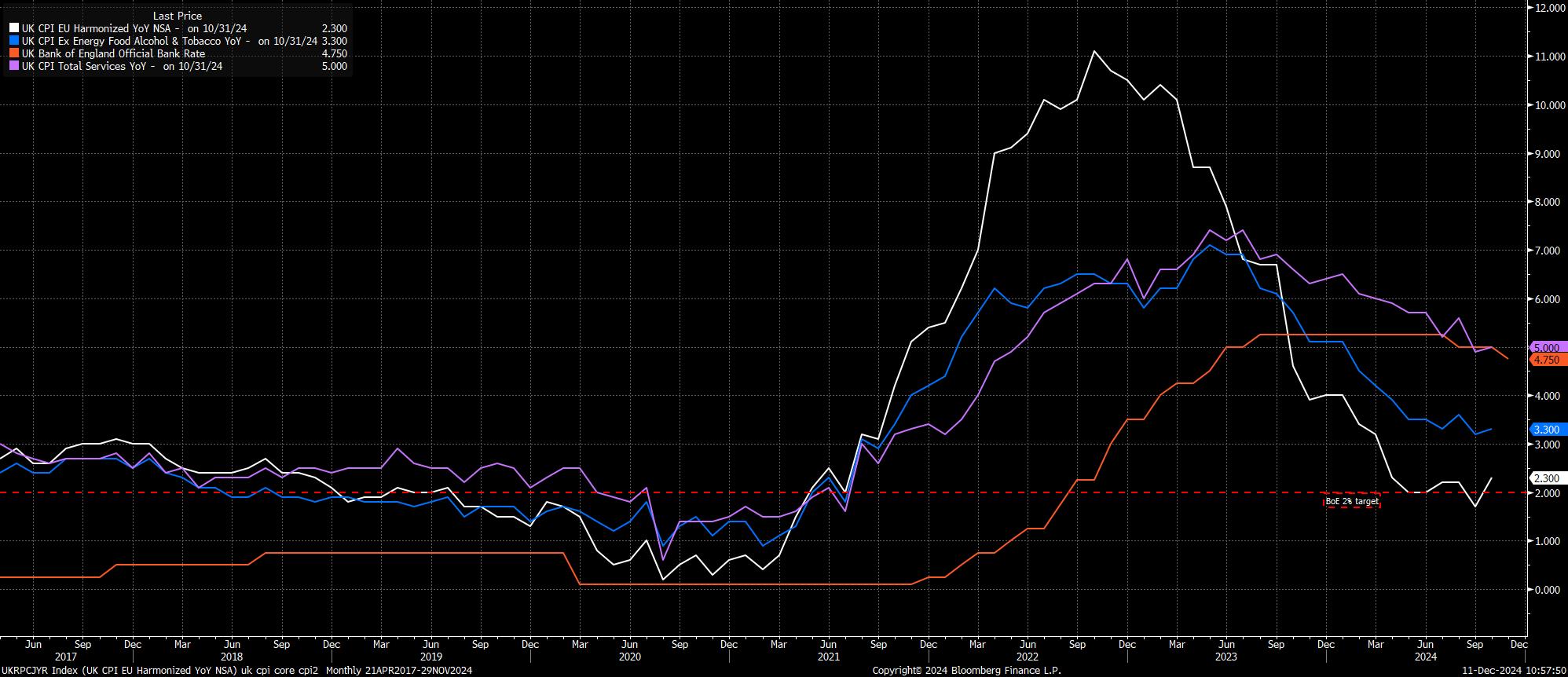

Headline inflation rose 2.3% YoY in October, largely due to an increase in consumer energy prices, though a further rise in headline CPI is foreseen in November, with figures due a day prior to the BoE’s policy announcement. Of more concern to policymakers will likely be continued signs of price pressures becoming embedded within the economy – core prices rose 3.3% YoY in October, while services inflation continues to run around 5% YoY – both, clearly, levels that are incompatible with a sustainable return to the 2% target, and which reinforce the MPC’s cautious approach.

Meanwhile, increasing slack continues to emerge in the labour market.

Unemployment rose to 4.3% in the three months to September, its highest level since May, though concerns persist over the quality of the ONS’ labour force survey, with the data still notoriously unreliable and volatile.

Earnings growth, meanwhile, has continued to moderate, with regular pay rising 4.8% YoY over the aforementioned period. That said, while pay growth has moderated, both regular and overall earnings growth remains at a pace that is likely too high for the MPC’s liking. This is particularly true considering that the full impacts of the above-inflation public sector pay increases announced in the summer will only feed into the data during the fourth quarter.

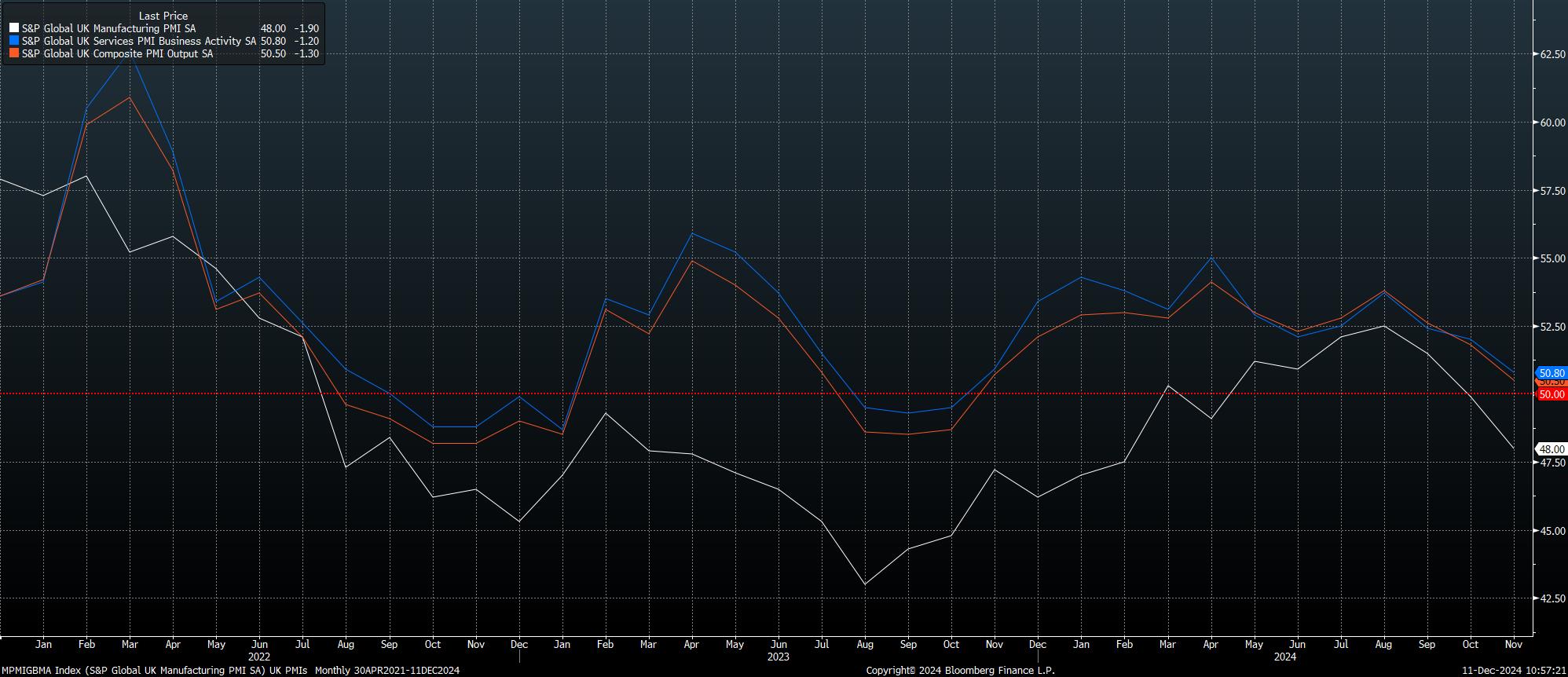

At the same time as price pressures remain stubborn, and the labour market loosens, the economy more broadly shows signs of waning momentum.

GDP grew by just 0.1% QoQ in the three months to September, with growth likely having been severely dented by the marked increase in uncertainty prior to the October Budget. Since then, momentum has continued to wane, with November’s PMI surveys pointing to the fastest manufacturing contraction since February, and to the weakest service sector growth in a year.

Against this backdrop, the MPC’s cautious and gradual approach to policy easing remains a logical one, particularly considering that the full impact of October’s Budget announcements – particularly the changes to national insurance contributions – will not be known until the second quarter.

Consequently, the base case remains that the MPC will next deliver a 25bp Bank Rate cut in February, in conjunction with the release of a fresh Monetary Policy Report. Quarterly cuts of said magnitude are then likely to follow throughout 2025, though risks to this view are tilted to a more dovish outcome, considering the potential for increased labour market slack, and waning overall economic momentum, to crush demand, and thus result in underlying price pressures fading more quickly than expected.

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.