Analysis

Big Themes For 2024 – What The Year May Bring For The US Economy

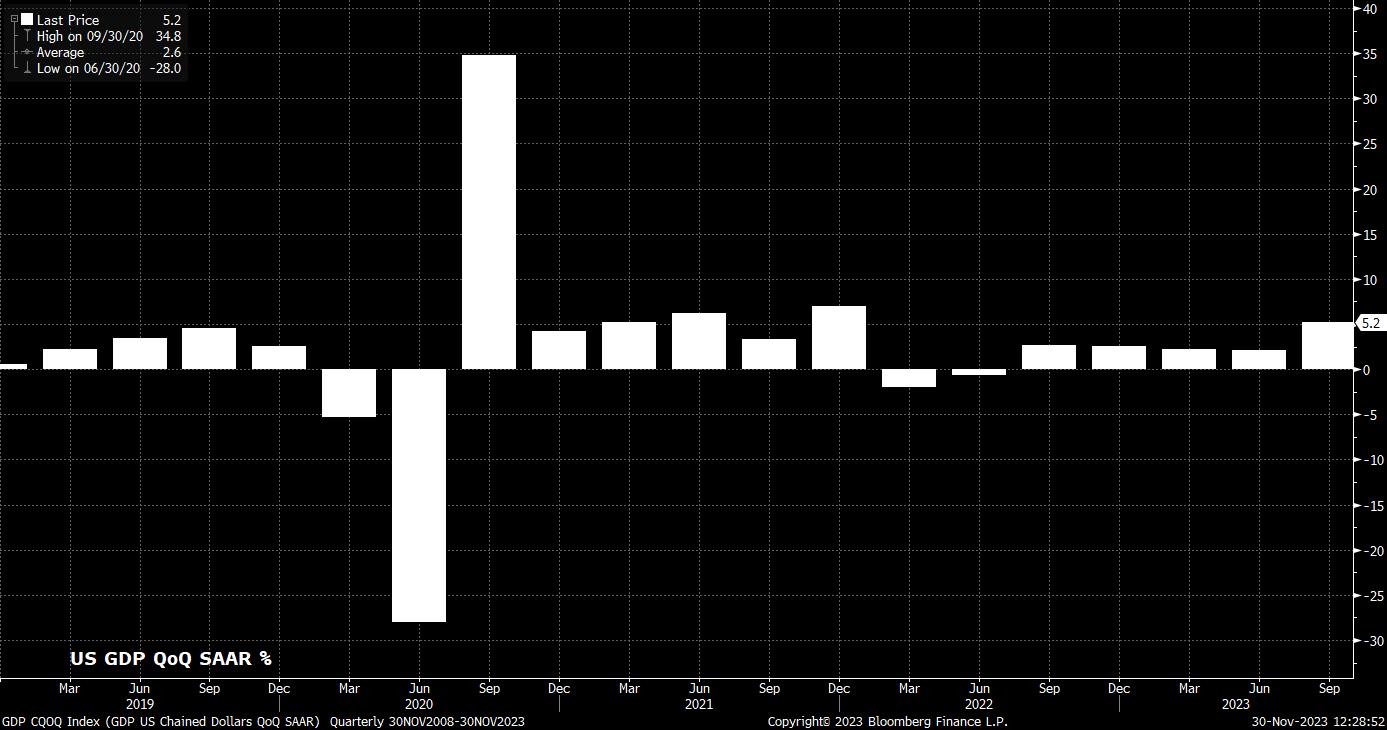

As noted, while 2023 proved a year of surprising resilience for the US economy, the year ahead is unlikely to present as smooth a set of sailing conditions. Nevertheless, as well-evidenced by the ‘US exceptionalism’ that drove financial markets for much of last year, the pace of economic expansion recorded over the year, including a sizzling 5.2% annualised QoQ GDP increase in Q3, coupled with the rapid and substantial progress made on returning inflation to the Fed’s 2% target, has been little short of incredible.

More challenges, however, lie ahead in 2024. Principally, the question facing the economy, and policymakers, is the extent to which the ‘last mile’ of the disinflation process can be completed, without tipping the US into recession. Although, almost certainly, the FOMC delivered their final hike of the cycle in July, the lagged effects of the tightening delivered to date will continue to be felt over the coming 12 months, further slowing economic momentum as the year progresses.

As such, the risk of a deeper downturn is higher in 2024 than it was in 2023, with those intensifying monetary headwinds set to combine with a greater fiscal drag, causing a broad-based deterioration in demand, signs of which are already beginning to emerge in the most recent PMI surveys.

In turn, said faltering demand is likely to result in a continued softening in the labour market. While headline nonfarm payroll growth has remained relatively resilient, averaging just over 200k on a rolling 3-month basis, other job market indicators are painting a rather more dismal picture.

Unemployment, for example, has already risen 0.5pp from cycle lows to 3.9%, as at end-October, with such a rise being perilously close to triggering the widely observed ‘Sahm Rule’, which has previously been a reliable indicator of recession, albeit one which has little predictive power as to the timing of such a slowdown. In any case, other labour market indicators also imply a softening in conditions of late, with participation dipping to 62.7%, while underemployment has also begun to rise.

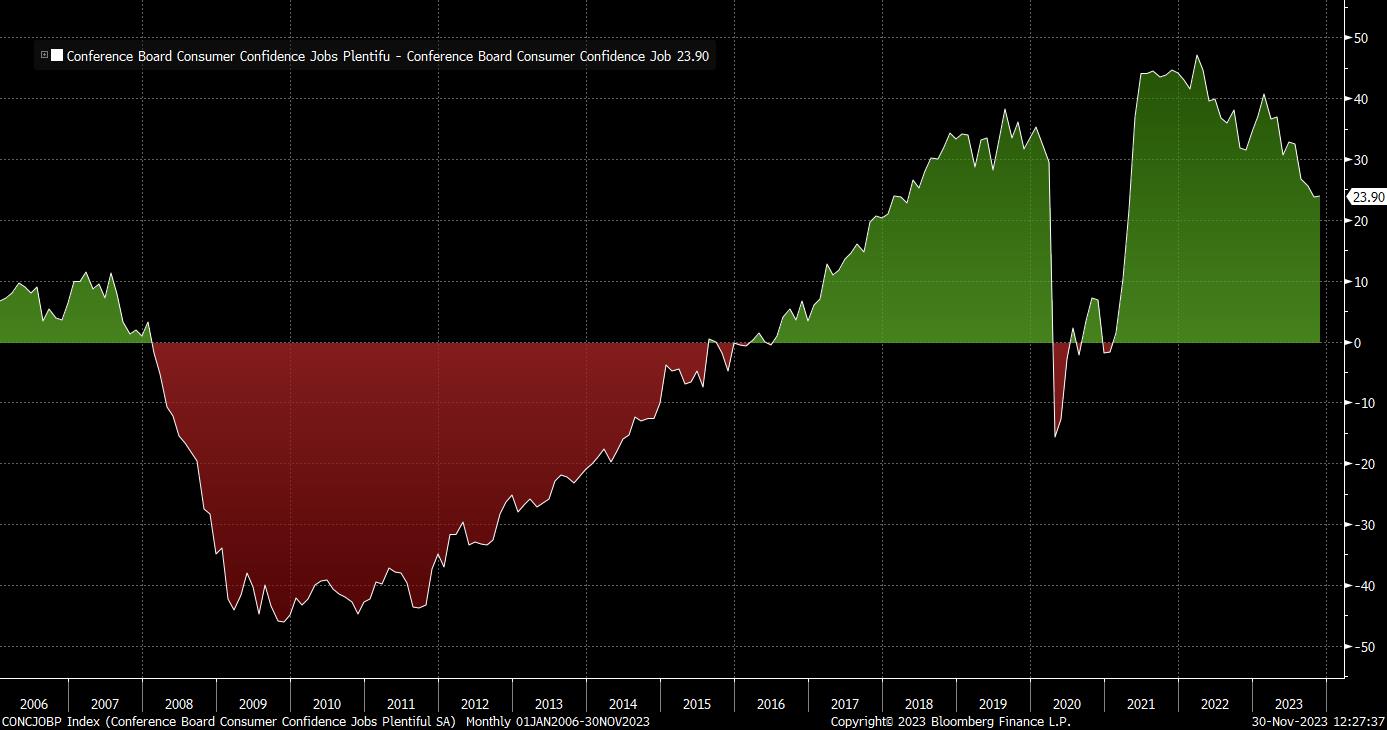

Furthermore, recent sentiment surveys, per the Conference Board, have indicated a substantial rise in the perception of jobs being ‘hard to get’, along with a substantial fall in the perception that jobs are ‘plentiful’, in turn narrowing the labour differential. As demand wanes, and the impact of tighter financial conditions continues to be felt, there seems little reason for these trends to reverse course, likely leading to unemployment rising into the mid-4% region next year.

A softer labour market, though, along with ebbing demand, is exactly what the FOMC have spent the last 18 months attempting to achieve, given that both should cement the disinflationary path that the US economy is currently on.

As with most other DM economies, US inflation has cooled significantly from the highs seen in mid-2022, though much of the moderation seen in price gauges over this time has come by virtue of goods. Meanwhile, core CPI remains at 4% YoY, double the FOMC’s objective, while core services ex-housing inflation, a gauge that policymakers have watched intently of late, is also elevated, with progress on both measures having stalled a little in recent months. A looser labour market should relieve some price pressures here, though the FOMC are likely to want to see significantly more progress on returning services inflation to target before openly considering the prospect of rate cuts.

In fact, policymakers do have a relatively difficult balancing act to consider next year, needing to ensure that inflation returns swiftly to target, while attempting to engineer a soft landing, with the added complication of next year’s presidential election running the risk of monetary policy again becoming increasingly politicised.

There is also the issue of markets pricing an increasingly aggressive pace of cuts, with the first 25bp rate reduction now fully price for May, and a total of four such cuts priced in over the entirety of 2024. While policymakers may, in an ideal world, wish to push back on this punchy pricing, there is little in incoming economic data that provides them with the ammunition to do so.

Furthermore, it is important to recognise that, even for the relative stance of monetary policy to remain unchanged over next year, some degree of cuts to the fed funds rate will be necessary, else the real fed funds rate will rise, and financial conditions tighten further, as inflation continues to fade. Consequently, while belief in the ‘higher for longer’ policy stance has begun to wane, it may be more apt to rename the Fed’s 2024 stance as ‘tighter for longer’, with current market pricing seemingly over-the-top, barring a deep recession, and a return to the zero-rate era seen post-GFC almost entirely off the cards.

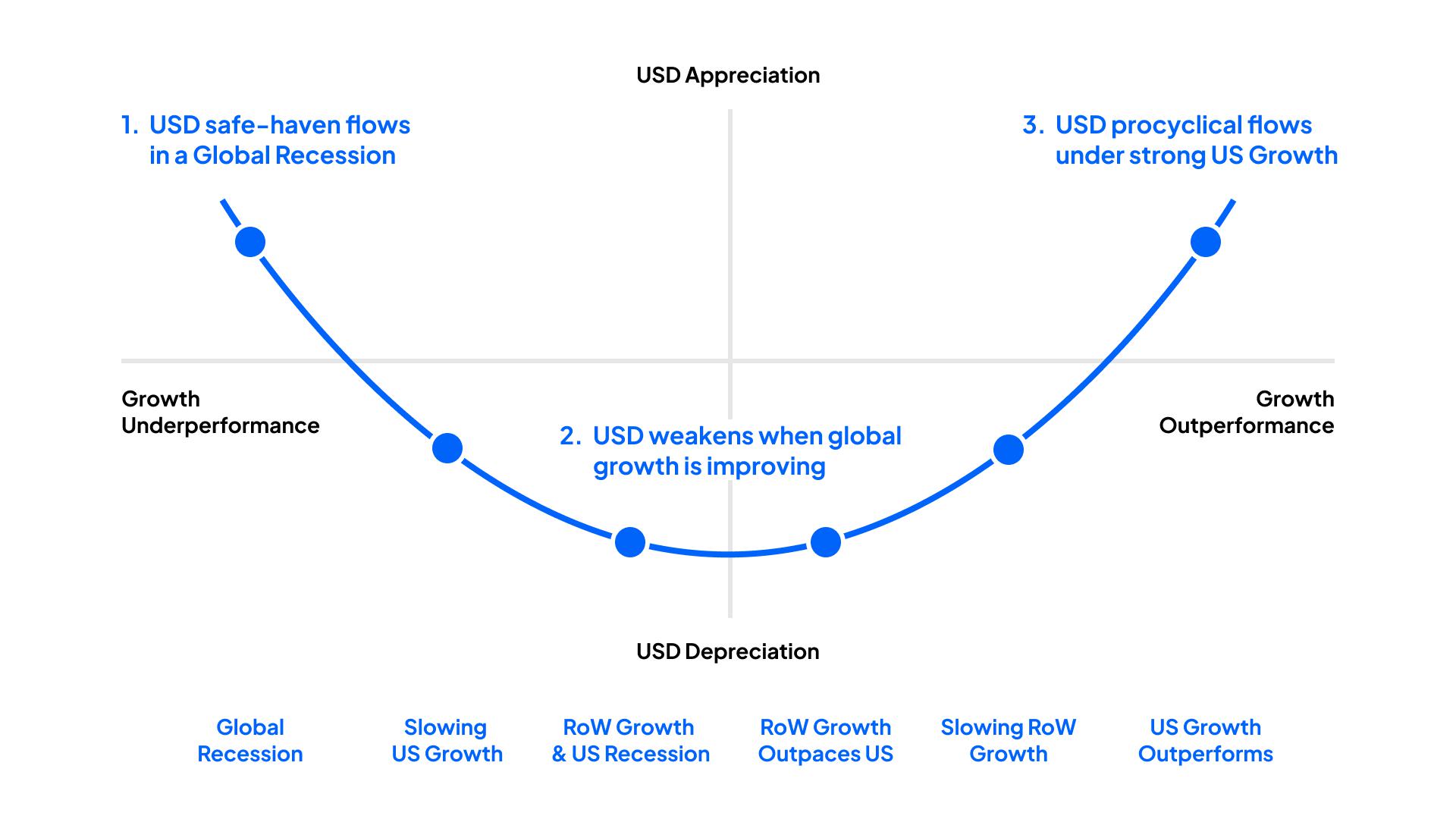

Putting all of this together for the USD produces a baseline scenario whereby markets continue to move towards the middle of the so-called ‘dollar smile’. Such a move should pan out as US economic growth ‘catches down’ to that of G10 peers, and as the disinflation process permits the Fed to begin gradually dialling down the fed funds rate. Of course, risks remain to this view, principally in the form of a renewed flare-up in geopolitical risk, along with the potential for, as seen in 2023, the US economy to confound expectations once again.

Related articles

The material provided here has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and as such is considered to be a marketing communication. Whilst it is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research we will not seek to take any advantage before providing it to our clients.

Pepperstone doesn’t represent that the material provided here is accurate, current or complete, and therefore shouldn’t be relied upon as such. The information, whether from a third party or not, isn’t to be considered as a recommendation; or an offer to buy or sell; or the solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security, financial product or instrument; or to participate in any particular trading strategy. It does not take into account readers’ financial situation or investment objectives. We advise any readers of this content to seek their own advice. Without the approval of Pepperstone, reproduction or redistribution of this information isn’t permitted.